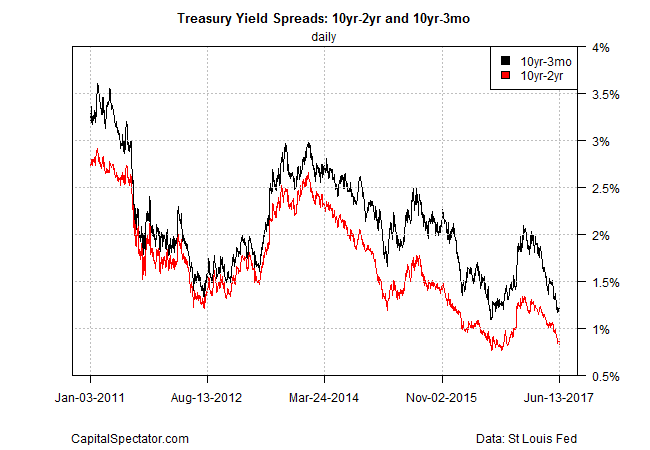

The Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates today – at a time when the Treasury yield spread has become relatively compressed. That’s a warning sign, according to the historical record. The question is whether the shelf life for this analysis has expired.

Tim Duy, a professor at the University of Oregon, reminds that “recent history suggests that the greatest risk of recession occurs if the Fed continues to tighten after the initial inversion of the yield curve, which happened prior to the last two recessions.” The curve isn’t inverted, but it’s getting close. Meantime, the Fed is widely expected to lift interest rates again today, laying the ground work for squeezing the curve a bit more.

Consider the 10-year/2-year Treasury yield spread, which fell to 83 basis points yesterday (June 13), based on daily data via Treasury.gov. That’s the smallest spread since last October and slightly below the long-term average of 93 basis points over the past four decades.

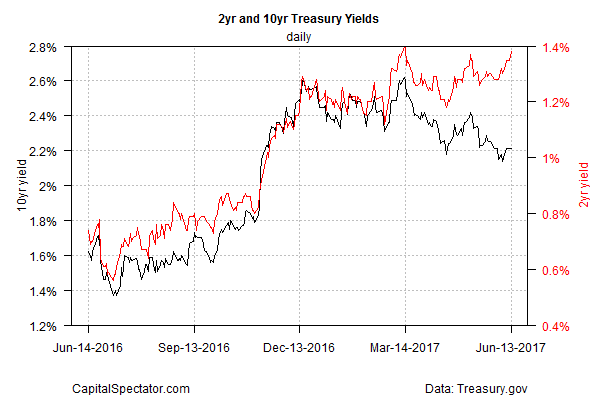

The recent decline in the spread is a byproduct of a higher 2-year yield and a falling 10-year yield. The two yields had been tracking each other closely up until March, when each went their separate ways. The 2-year yield remained relatively stable, with a slight upside bias, while the benchmark 10-year rate declined. As of yesterday, the 2-year yield, currently at 1.38%, is close to its highest level since the last recession. Meantime, the 2.21% 10-year rate is near a seven-month low and far below its 4% post-recession high.

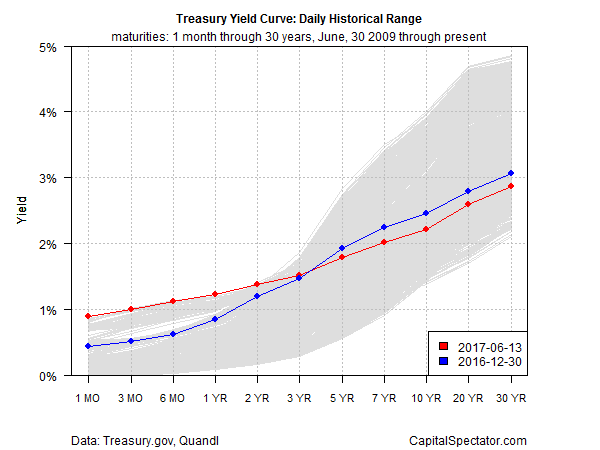

Reviewing how the entire yield curve has changed since last year’s close highlights the tightening bias of late. Rates on the short end of the curve up through the 2-year maturity are at or near the highest levels since the recession ended in mid-2009. Maturities from 5-year up, by contrast, are at middling levels and have fallen so far this year.

Let’s be clear: recession risk is low at the moment. The probability is virtually nil that the NBER will label May as the start of a new downturn in the US, based on data published to date, and near-term estimates of recession risk through next month are expected to remain low, as outlined in the June 11 edition of The US Business Cycle Risk Report.

What, then, should we make of the tightening yield curve? Is it an early warning sign that trouble’s brewing for the US economy? Or has the extraordinary monetary policy of the last decade rendered yield-curve analytics null and void for analyzing the business cycle?

No one knows the answer to that question, which means that monitoring the yield curve should remain a high priority. That said, there’s no guarantee that any one indicator, even one as robust as the yield curve, is destined to forever dispense flawless signals. In fact, history clearly shows that different indicators stumble at times, usually at different times. A stronger solution for estimating recession risk requires that we monitor a diversified set of indicators.

Keep in mind, too, that the Fed is certainly aware of the yield-curve history, which implies that the central bank will be reluctant to create conditions that raise recession risk.

Tim Duy expects that the current expansion is on track to match the previous record:

“The current expansion began in June 2009. If it holds until June of 2019, it will match the previous record. By my reckoning, the economy will very likely make it to that point and beyond.”

The unknown factor is whether the Fed will maintain monetary conditions that support Duy’s forecast. If the Fed’s policy decisions become increasingly hawkish over the next 12 months, the risk of a recession will rise, he advises. But that appears to be a low-risk scenario, in part because of softer inflation and employment data in recent months that may influence the central bank’s plans.

Even if the yield curve inverts, Duy thinks the risk will remain low for a recession in the near term. “There is a delay between yield curve inversions and recessions that makes a downturn in 2018 very unlikely,” he explains. “Prior to the past two cycles, the yield curve inverted more than a year before the subsequent recession.”

Perhaps, but the recurring question is always lurking when it comes to analyzing the business cycle after the upheaval of the Great Recession: Is it different this time? Duy doesn’t think so. Although economy tends to be more resilient than generally assumed, “the economy has not proved resilient to excessive monetary action.”