Macroeconomic risk factors are combining into a heavy stagflation potential.

The CPI inflation rate for September has turned out 8.2% on a yearly basis, 0.1% higher than the expected consensus. This means that the Fed’s interest rate hikes, as the fastest since the early 1980s, hadn’t been as effective.

In turn, the Fed is ready to further deploy its monetary tools, as a part of its dual mandate to combat inflation and unemployment. However, the problem arises when these tools cause more side effects due to underlying macroeconomic conditions.

What Is A Stagflation?

Stagflation combines the worst aspects of stagnation and inflation, as they feed on each other. While inflation causes the prices of goods and services to soar, stagnation is marked by high unemployment and decreased economic growth, but not going into the negative territory.

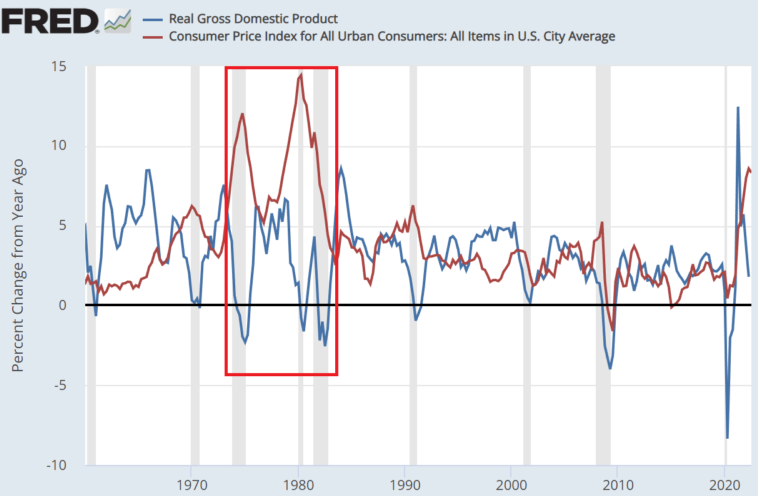

In economic theory, stagflation was thought to be impossible. That is, until the 1970s oil crisis triggered five consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. Across major world markets, stagflation lasted from 1973 to 1982.

Inverted GDP and CPI are the hallmarks of stagflation. Image credit: fred.stlouisfed.org

During that period, inflation spiked from 2.8% in the 1960s to over 7% in the 1970s, peaking at just over 14% CPI in Q2 1980. Once Fed Chair Paul Volcker began to aggressively raise interest rates, it eventually came dome. The current Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted in his August Jackson Hole speech.

It should be noted that stagnation is not the same as a recession. As seen in the shaded areas above, representing recessions, economic shrinkage can happen during stagflation. In other words, stagflation is marked by a prolonged period, while recessions are short and corrective.

Although there is no coherent framework on stagflation causes, it was telling that it was triggered by OPEC’s decision in 1973 to place an oil embargo on the West. Because the price of goods and services relies on stable oil prices, its sudden spike made everything more expensive, leading to both job losses and soaring inflation.

Present-Day Stagflation Risks

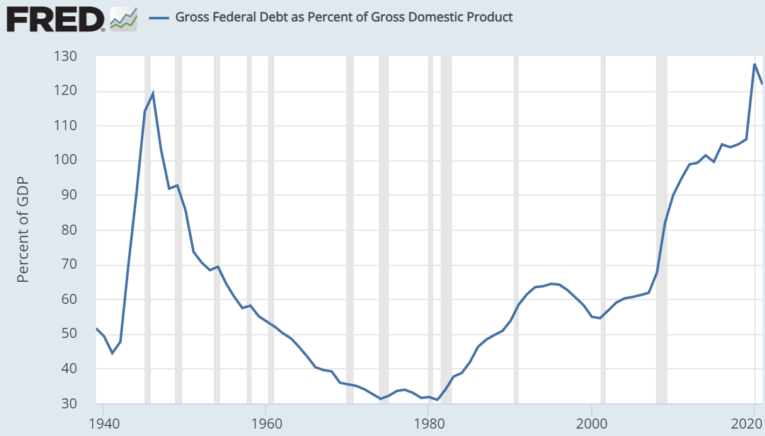

In 1973, the US national debt was $458 billion, or 33% being the debt-to-GDP ratio. In 2022, the US national debt rose to $31 trillion, or 124.7% as the debt-to-GDP ratio, higher than at the end of World War II.

The higher the debt, the higher the default risk. Image credit: fred.stlouisfed.org

Just like for regular households, such unfavorable debt indicates default risk. According to the World Bank, the 77% debt-to-GDP ratio threshold is when economies start to experience bouts of economic slowdown and stagnation. That inevitably happens because countries have to service the interest on their sovereign debt.

The US represents this sovereign debt as bonds – debt securities issued by the federal government so it can continue spending and meet other obligations. This is where the macroeconomic ground is ripe for chaos.

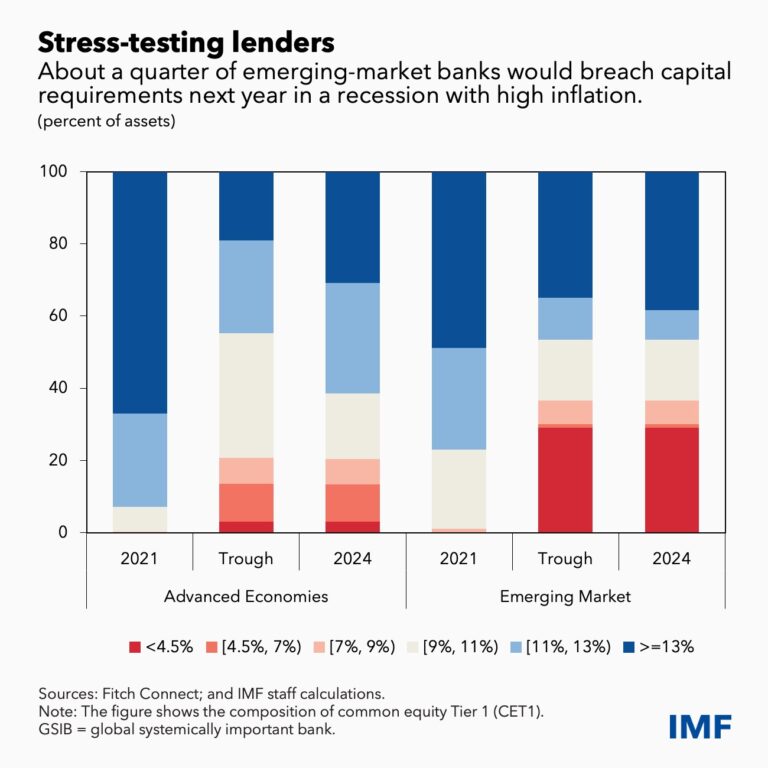

The sovereign debt can only be serviced if issued bonds are bought by investors. But, across the world’s central banking system, the demand for bonds is lacking. In turn, central banks are forced to increase bond yields to make them more attractive.

At the same time, central banks are hiking interest rates to combat inflation, potentially triggering a liquidity crisis. This was recently noted both by the US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen (former Fed Chair) and the IMF.

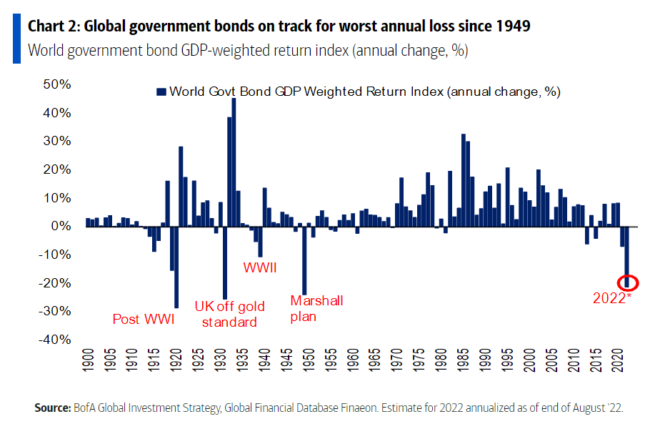

Another exacerbating factor is that other central banks rely on the dollar as the global reserve currency. With the Dollar Strength Index (DXY) going up +17.72% year-to-date, it forces many foreign buyers out of the market. Consequently, the year-to-date annualized loss in government bonds is the worst since 1949.

Is the Confidence in Central Banking Waning?

In a centralized banking system, markets rely on institutions to steer the economic vessel. By the very nature of the fiat (by decree) system, it relies on institutional trust. Former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh noted as much in 2014. This was years before the Fed stimulated the economy by increasing its balance sheet by $4.5 trillion in the last two years, triggering the present inflation spiral.

“Balance-sheet wealth is sustainable only when it comes from earned success, not government fiat,”

Unfortunately, government officials have been issuing incoherent messaging for the last two years, often contradicting what they say within days. Case in point, Janet Yellen noted two days ago that “I don’t think we’ve seen anything that rises to the level of a serious concern.”

Yet, only a day later she stated the complete opposite, “We are worried about a loss of adequate liquidity in the market”. This has been a recurring pattern throughout the last two years, neatly compiled here.

With such confidence-eroding messaging, the Fed is now in a tough position. The world’s largest central bank is now in a position in which further rate hikes risk destabilizing the world’s existing financial system.

On the other hand, the Fed could start re-inflating the system, which would debase the dollar and prolong inflation. In combination with the self-inflicted energy crisis across Europe and the recent OPEC decision to cut oil production, the macroeconomic ground is fertile for stagflation.