Most investors–and investment analysts and managers as well–tend to get fully wrapped up in short-term news and market movements. At times, it’s helpful to step back to observe markets and market-moving fundamentals from a distance.

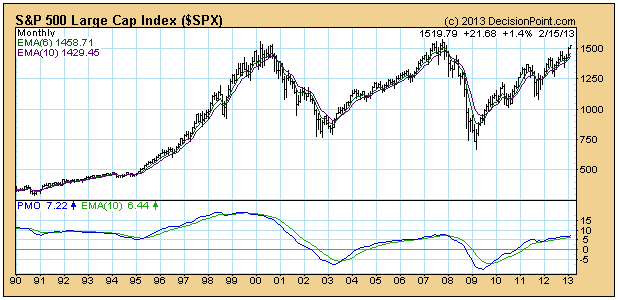

In the early weeks of 2013, the S&P has climbed above the 1500 level, approaching highs that marked the market peaks in 2000 and 2007. Since the turn of the century, investors have witnessed two destructive bear markets followed by two extended bull markets, each essentially recouping the capital lost through the preceding declines. Examining a long-term price graph from DecisionPoint reveals an intriguing symmetry, but there are some interesting differences in the respective bull and bear legs.

Only a few panicky price dips in 2008-09 broke below the lower boundary of the 21st century range in the high 700s. The mid-1500s have marked the upper boundary.

The initial decline lasted three full years from early-2000 to early-2003. The 9/11 disaster in 2001 certainly cast a pall over the nation psychologically, but that cyclical bear market had already realized well more than half its ultimate losses by the time of the insidious attack.

The bear market from late-2007 to early-2009 was far more precipitous, covering a slightly larger price range in merely half the time. Debt problems that characterized both cyclical bear markets had become far more severe by mid-decade and led to frozen financial markets by early-2009. Distrust of others’ balance sheets led major banks to refuse credit even to some of the world’s largest financial institutions. Only unprecedented intervention and rescue money from government entities reliquified the financial system and prevented a monumental economic collapse. The jury is still out on whether or not the ultimate costs of that intervention will prove more onerous than the pain avoided.

As confidence gradually grew that the system was not about to relapse, stock prices again began to rise. But the cyclical bull market that began in March 2009 and endures today has some noteworthy differences from its two predecessors. The move from below 800 up to the peak in early-2000 took a mere three years. It was interrupted by just one pullback of consequence, the precipitous price decline in 1998 corresponding with the Russian debt default and the collapse and rescue of Long Term Capital Management.

The next advance of about 800 S&P points took approximately four and a half years from early-2003 to late-2007. It was noteworthy for its lack of even a single price decline of 10% or more until shortly before the ultimate price peak. Investors became increasingly emboldened–despite burgeoning debt burdens around the world—by the belief that the “Greenspan put” guaranteed a Federal Reserve rescue effort should stock prices weaken. As a result, a buy-the-dips mentality led to increasingly quick trigger fingers every time stocks paused for a breath. Dips became almost non-existent until prices rose above 1500.

The current cyclical bull market has a different look from its immediate predecessors. Similar to 2003-07, this advance took just about four years to climb above 1500. Dissimilarly, the path has not been a smooth one. The economic recovery since 2009 has been the weakest in the post-World War II era. Debt problems have continued to grow worldwide, leading to sovereign bankruptcies in several countries, with defaults avoided only by central bank rescues. In the U.S., stock prices experienced major declines in 2010, 2011, and 2012 as Fed stimulus programs approached their scheduled terminations. Unwilling to allow a recession while monumental debt burdens remained, the Fed in each instance figuratively revved up its printing presses and announced another round of stimulus with the acknowledged goal of lifting stock prices. So far that move has worked to lift prices back to their former 2000 and 2007 levels. So persistent and successful have been the Fed’s efforts in this cycle that the “Bernanke put” has acquired the status of its immediate predecessor, and many investor confidence surveys have risen back to their 2007 levels.

No one knows how long that confidence will last. Clearly, the Fed will bend every effort to push stock prices through the highs reached in 2000 and 2007. The promised unlimited stimulus, however, continues to expand already extremely dangerous levels of government debt. Stock ownership today constitutes a bet that the Fed will win its dangerous gamble. And a growing portion of the investment community is willing to make that bet. Should confidence wane for any reason, it may be helpful to remember that prices were cut in half the last two times the S&P 500 rose to these levels. And at both those prior peaks, debt levels were significantly lower than today’s.

Investors willing to speculate on continued Fed success should carefully calculate how they will protect assets should the Fed’s best efforts again fail to support stock prices, as has occurred numerous times over the past century.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Investing: A Look At The Forest, Not Just The Trees

Published 02/17/2013, 02:00 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Investing: A Look At The Forest, Not Just The Trees

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.