This post goes carefully through ownership and trends in holding of Treasuries. It concludes that official holders, as in governments, look likely to further reduce their stakes, but that this ironically does not mean the demise of the dollar as reserve currency, at least in the near to intermediate term.

This post also helps correct a misperception that seems widespread among readers: that foreign governments are the main buyers of Treasuries. US investors have been and remain the dominant holders.

The trade war launched by the Trump administration follows a longer-term pattern of geo-economic fragmentation, but it dwarfs all prior expectations. This column looks beyond the trade war, asking if, in a more fragmented global economy, official investors should continue to hold US federal debt to the same extent as before. The answer is likely no, due to the increasing exchange rate risk on this debt as global trade stalls. Yet this does not imply the demise of the dollar as the global reserve currency, unless economic rationale fails to win precedence over brinkmanship.

For more than a decade, numerous factors have been pushing the world economy towards geo-economic fragmentation in response to disruptions in supply chains and security considerations (Boeckelman et al. 2024), automation (Faber et al 2025), China’s policy to intensify trade with the African continent (Amedolagine et al 2024), and the deepening of the European Single Market (Panon et al. 2025, Arjona and Revoltella 2024).

The trade war launched by the Trump administration fits in this longer-term tendency, but it dwarfs all prior expectations (Grzana and Ilzetski 2025) and will only have losers (Eiffinger 2025). A new status quo is likely to emerge from negotiations (Anil 2025), but the transition will be painful (Bertoldi and Buti 2025), as economic growth is set to stall with weaker competition and specialisation (Bombardini et al. 2025, Moro and Nispi Landi 2025). Moreover, the loss of diversification benefits of global integration may lead to more macroeconomic volatility (Attinasi and Mancini 2025).

The trade war seems to be motivated by the inequalities that may have resulted from the dollar’s reserve currency status (Monteiro and Piermartini 2024). Meanwhile the US administration is downplaying its benefits for the safe asset status of US Treasuries (Choi et al. 2024, Subacchi and Van den Noord 2023), even if this has helped to finance US defence expenditure on favourable terms (Yared 2024). Claims that tariff revenues will offset the loss of this fiscal advantage look groundless (Evenett and Fritz 2025).

With the global economy headed for more geoeconomic fragmentation, we use a three-country dynamic general equilibrium model built around stylised representations of the US, the euro area, and China to examine what this might imply for the global demand for US federal debt as the main reserve asset.

Who Holds Treasuries?

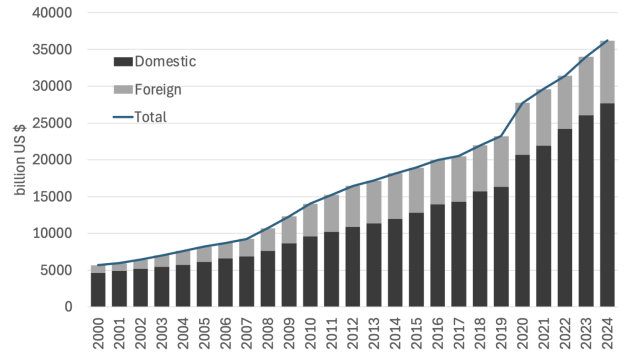

The world has accumulated large international dollar reserves, mainly invested in US Treasury Bonds (Figure 1). Around one-quarter of US federal debt (of over 120% of US GDP) is funded abroad owing to its safe asset status and being dollar-denominated.

Figure 1: Foreign and Domestic Holdings of US Federal Debt

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

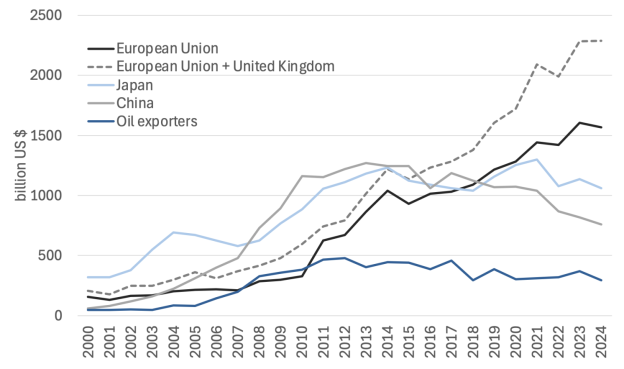

Figure 2: Foreign Holdings of US Federal Debt by Country or Jurisdiction

Source: US Department of the Treasury. The jurisdictions included in this figure are the five largest investors in US Federal debt. The bulk of the EU holdings of US several debt are reported by its main financial centres, i.e. Ireland, Luxembourg and Belgium (where SWIFT and Euroclear are established).

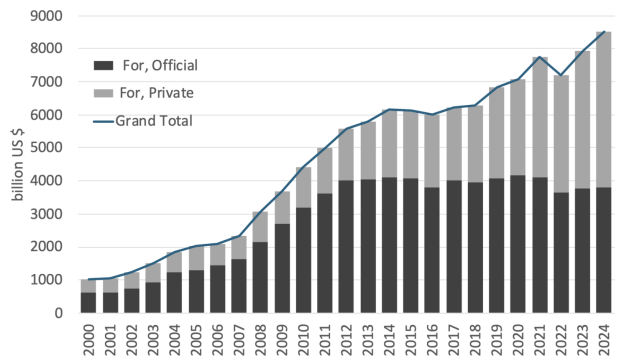

Figure 3: Official and Private Foreign Holdings of US Federal Debt

Source: US Department of the Treasury.

In past decades, China and Japan have been the largest holders of such debt (Figure 2). However, weak returns on US debt following the Global Financial Crisis and geopolitical considerations, including sanctions on Russia’s dollar reserves, have prompted China to reduce its Treasury holdings in favour of other currencies and gold (Ahmed and Rebucci 2025, Aiyar and Ilyina 2023, Eichengreen 2023, Laser et al. 2024). While this affects most developing countries (Bordo and McCauley 2025), the portfolio shift in China is systemic.

EU member states and the UK have picked up the slack so far. Their increased demand for US Treasuries is mainly private, while official holdings have stalled (Figure 3). However, the deeper geo-economic fragmentation spurred by Trump’s aggressive trade policy will entail valuation risks for dollar-holders. In a recent study (Subacchi and Van den Noord 2025) we assess this risk, and the results are briefly discussed in the remainder of this column.

Analytical Framework

We set up a three-country model in which international trade is settled in the currency issued by the ‘monetary hegemon’. The two other countries accumulate foreign exchange reserves by investing in sovereign debt issued by the hegemon, which is considered safe and liquid. One of these countries – the ‘conventional creditor country’ – allows private investors to hold foreign sovereign debt while the other – the ‘emerging creditor’ – prohibits this.

We distinguish between two periods – the ‘short run’ and the ‘longer run’ – with all asset and liability positions unwinding at the end of the second period. Monetary policy does not play an explicit role in determining the overall price level. As a result, movements in the real exchange rates are not broken down into movements in nominal exchange and inflation rates.

The real interest rate is the key adjustment variable to establish the optimal mix between home-produced and imported goods in each country over both the short and long term (intertemporal equilibrium), while the real exchange rates adjust to establish the optimal mix of consumption of home-produced and imported goods in each country (intra-temporal equilibrium).

In the ‘conventional creditor’ country, the accumulation of reserve assets by the private sector is a function of the opportunity cost of holding them. This cost is the spread between the risk-adjusted yields on domestic sovereign debt and the reserve asset and the expected exchange rate loss on that asset. The latter is due to the monetary hegemon’s need to run a trade surplus in the longer term to finance the repayment of its foreign-held sovereign debt.

This approach (see also Blanchard et al. 2005) reflects the rising geopolitical tensions coupled with the aggressive trade policy of the Trump administration. It sharply contrasts with the assumption that such debt could build up forever, as embedded in models with an infinite time horizon (e.g. Felbermayr et al. 2023) or in static ones (Cheng and Zhang 2012).

Official investment in the hegemon’s sovereign debt is treated as exogenous in the model. However, official investors face opportunity costs on their holdings as well. While these costs are assumed to have no impact on these investments, it is nonetheless important to compute them to assess the economic soundness of these investments.

Scenario Analysis

The model and shocks are calibrated to loosely reflect stylised empirical realities. Starting from symmetric equilibrium (Scenario 0, without cross-border asset holdings), we generate two scenarios. In Scenario 1, the ‘conventional creditor’ and subsequently the ‘emerging creditor’ invest in the monetary hegemon’s debt. Next, the hegemon ‘consumes’ some of the fiscal space thus created by running a larger fiscal deficit. In Scenario 2, we evaluate the impact of geo-economic fragmentation on the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets, and how this cost changes if these holdings are restrained.

According to our simulations of Scenario 1, the demand for reserve assets by the creditor countries leads to an increase in the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets, due to higher real interest rate spreads of the latter against the hegemon and a stronger short-term but weaker long-run outlook for the real exchange rate of the reserve currency. The latter occurs because the hegemon runs a wider trade deficit in the short run and a wider surplus in the longer run to finance its foreign debt repayment.

When the hegemon runs a loose fiscal policy, the favourable yield spreads (for the hegemon) evaporate as the real exchange rate weakens further in the longer run. Since the exchange rate movements outweigh the narrower yield spreads, the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets rises further for foreign investors.

In Scenario 2, we assess the impact of geo-economic fragmentation, which we gauge by increasing the relative utility attached to domestic goods in the intra-temporal utility functions. Next, we assume a cut in the demand for reserve assets, first by the emerging creditor country and subsequently by the conventional creditor country.

Assuming that the demand for reserve assets by the creditor countries remains unchanged, the real exchange rates (and terms of trade) of the monetary hegemon against the other countries must strengthen in the short run to produce the required trade deficit to absorb the demand for its debt. However, they weaken in the long run when this foreign debt is repaid, while investors experience a valuation loss on their holdings. As a result, the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets increases, on balance, for both creditor countries, even though the real yield on the reserve asset increases.

Creditor countries, therefore, reduce their holdings of reserve assets, starting with the emerging creditor country. The real exchange rate of the later now appreciates while the yield on its reserve assets rises. The incentive for further cutbacks weakens as a result.

In a final step, we assume that (public and private) investors in the conventional creditor country follow suit, since the opportunity cost is still considerably higher. The impact of this change on the real yield on the reserve asset and the evolution of the real exchange rate is similar as in the previous step where the emerging creditor cut its holdings of reserve assets. As a result, its opportunity cost recovers somewhat further, and a complete wipe-out becomes even less likely.

Conclusion

We examine whether dollar holders will continue to maintain their positions or reduce their exposure in response to geo-economic fragmentation. We show that the rationale of holding less US sovereign debt is compelling because the opportunity cost of holding it increases. However, cutbacks in the build-up of creditor countries positions of US sovereign debt lowers its opportunity cost. A collapse of the dollar’s dominant position is therefore unlikely, unless countries give precedence to geopolitical brinkmanship over economic rationales.

See original post for references