From a policy perspective, the decline in Chinese demand and the relative over-supply of commodities within China adds downward pressure to a variety of commodities. This situation is likely to continue. Last week, Bloomberg and the FT both noted the weak situation in the steel market:

China’s mills -- which produce about half of worldwide output -- are battling against oversupply and sinking prices as local consumption shrinks for the first time in a generation amid a property-led slowdown. The fallout from the steelmakers’ struggles is hurting iron ore prices and boosting trade tensions as mills seek to sell their surplus overseas. Shanghai Baosteel Group Corp. forecast last week that China’s steel production may eventually shrink 20 percent, matching the experience seen in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Medium- and large-sized mills incurred losses of 28.1 billion yuan ($4.4 billion) in the first nine months of this year, according to a statement from CISA. Steel demand in China shrank 8.7 percent in September on-year, it said.

Signs of corporate difficulties are mounting. Producer Angang Steel Co. (HK:0347) warned this month it expects to swing to a loss in the third quarter on lower product prices and foreign-exchange losses. The company’s Hong Kong stock has lost more than half its value this year. Last week, Sinosteel Co., a state-owned steel trader, failed to pay interest due on bonds maturing in 2017.

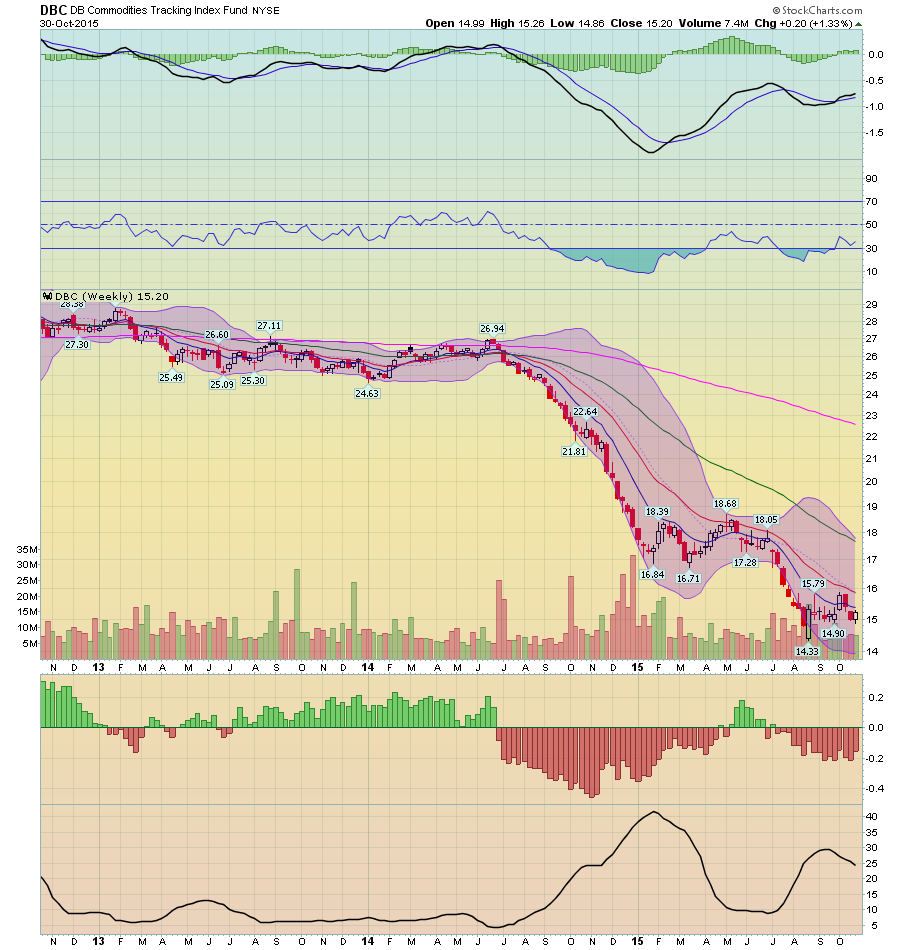

When steel weakness is combined with the decline in oil prices, the net impact on commodity prices is very large, as shown in this weekly chart of the PowerShares DB Commodity Tracking ETF (N:DBC), the tracking stock for the commodities complex:

Overall commodity prices dropped ~50% from their post-recession high. This decline is a primary reason for weak inflation at the international level – a situation that is confounding developed market central banks. In a speech several weeks ago, Fed President Brainard placed this commodity price weakness – typified by the Chinese steel experience -- into a broader perspective:

Downgrades to foreign growth affect the U.S. outlook through several channels. First, weak growth abroad reduces demand for U.S. exports. Second, the expected divergence in U.S. growth increases demand for U.S. assets, putting upward pressure on the dollar, which, in turn, weighs on net exports. The estimated effect of dollar appreciation on net exports has been shown to be substantial and to persist for several years. Weak demand weighs on global commodity prices, which, together with the effects on the dollar, restrains U.S. inflation. Finally, the anticipation of weaker global growth can make market participants more attuned to downside risks, which can reduce prices for risky assets, both abroad and in the United States--as we saw in late August--with attendant effects on consumption and investment.

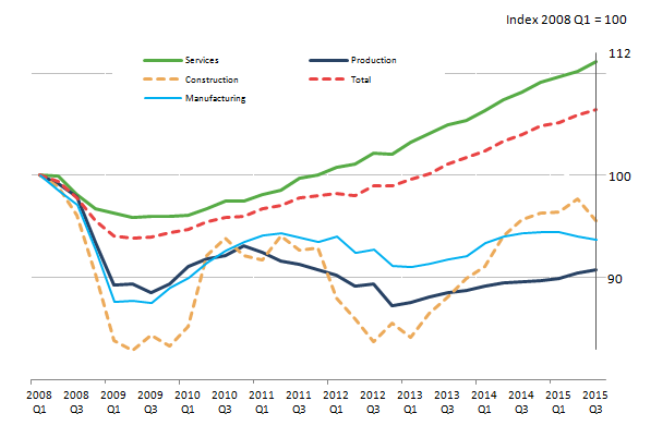

The ONS released 3Q UK GDP last week. The preliminary number was .5% M/M and 2.7% Y/Y. What’s most important about this data is the UK’s over-reliance on service sector growth; all other sectors are still below 1Q 2008 levels:

In fact, manufacturing and the broader industrial measure of production have been very weak since 1Q13.

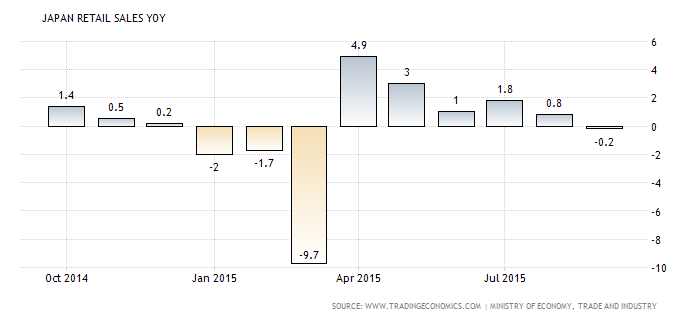

The Bank of Japan voted to maintain their current rate and asset purchase policy. But other news released this past week shows an economy that is weakening. Retail sales declined .2% Y/Y, continuing a declining trend that started in April:

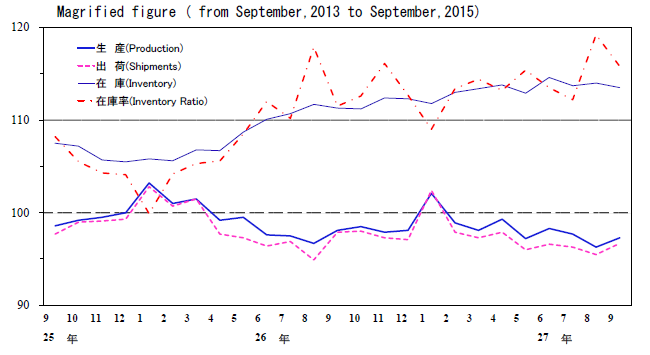

Industrial production increased 1%, but this was the first increase in three months. And as shown in this chart from the release, this number has been moving sideways for the last two years:

And the inflation rate was unchanged while core decreased .1% (Y/Y). Commentary regarding Japan is starting to acknowledge the potential shortfalls of Abenomics, which is typified by this piece from the Financial Times:

Mr Kuroda now faces a defining choice: either double up on his policy and further increase easing or take a more gradualist approach.

Accepting that the BoJ must simply wait and hope for 2 per cent inflation would be tantamount to a concession of defeat. People who have met the governor recently say he is sticking to his story: the BoJ’s policy is working, and a virtuous cycle between prices and wages is taking hold.

But if he chooses not to ease further on Friday, despite such a weak economic outlook, he risks signalling that a timely escape from deflation is beyond the BoJ’s power, triggering a collapse in his credibility and undoing any good that his policy may have done.

But others argue that Abe’s program is doing fine. Noah Smith at Bloomberg notes that since Abe took office, the working age population has declined. This means the appropriate measurement metric is per capital GDP, which has increased. Furthermore, the Chinese slowdown has negatively impacted Japan’s economy. This was an exogenous event for which policy makers must now make additional adjustments.

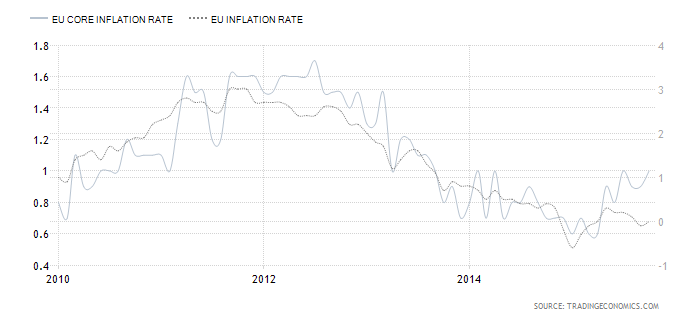

EU news was mixed. Total inflation increased 1% Y/Y while core was flat.

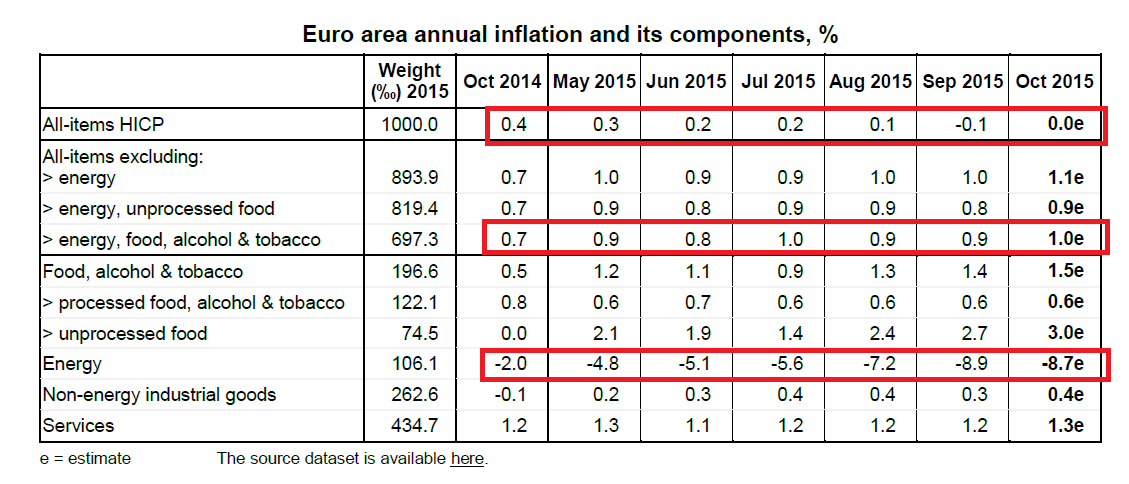

As shown in the following table from the EU release, core inflation has been declining at a slight pace for the last six months while total inflation has slightly increased. It appears the energy prices are the primary causal factor:

The unemployment rate declined to 10.8%. According to Businessindsider.com:

The eurozone just had its best quarter for unemployment since the beginning of 2007, according to official statistics showing September's numbers, which came out on Friday.

The unemployment rate fell to 10.8%, below August's 10.9%. 414,000 fewer people are out of work in comparison to the second quarter, the largest amount since the first quarter of 2007, according to IHS chief UK economist Howard Archer.

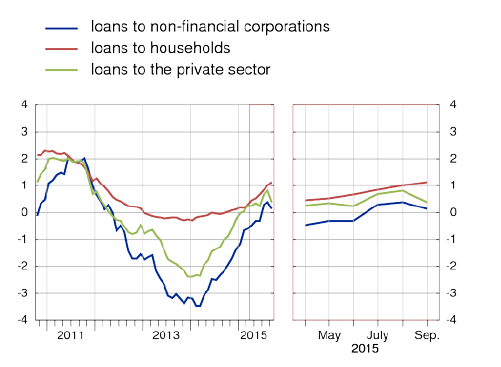

Finally, loans to households gained .1% although loans to businesses dropped:

Canadian GDP increased .4% in August. Furthermore, Statistics Canada revised higher previous monthly GDP figures for June and July, meaning Canada avoided a technical recession in 1H15. Goods producing industries snapped back in June and July, printing .8% and .7% increases. A mining industry rebound was the primary reason for these increases. As for the rest of the economy, the Financial Times wrote a good summary of Canada’s macro situation. It could be better. They’re over-relied on the oil industry, housing and health care for growth. This means overall productivity is weak. And while the loonie dropped about 25% in value versus the dollar over the last few years, other net exporters’ currencies have dropped a comparable amount, so exports can’t drive future growth. In short, the country is in a serious policy bind.

It's looking more and more likely that the ECB will add additional stimulus soon while the UK will remain on the policy sideline. Canada avoided a technical recession but still faces large economic problems. The Fed wants desperately to raise rates. Japan, on the other hand, appears to still be in a policy quagmire.