With all the recent negative news centered on China, it was probably only a matter of time before an analyst argued China would cause the next recession. Citigroup issued such a report this past week:

Citigroup Inc (NYSE:C). is sounding the alarm bells for the world economy.

In an analysis published late on Tuesday, the New York-based bank’s chief economist, Willem Buiter, said there is a 55 percent chance of some form of global recession in the next couple of years, most likely one of moderate depth and length.

He bases his argument on the high level of private sector debt in China:

The cause of his consternation is the immense debt that Chinese non-financial companies have racked up in a short period of time. Over the past decade, the indebtedness of China's private sector has exploded and exceeded that of the U.S., which Buiter pointed out has a much more advanced economy and sophisticated financial system.

Citigroup isn’t the first firm to raise alarms about China. McKinsey and Co. issued a report often touted by the FT which states Chinese debt is now 262% of overall Chinese GDP. And other FT articles written over the last 12-18 months voiced the same concerns. Don’t be surprised if other companies make the same prediction in the coming weeks. The impact of slower Chinese growth is already apparent in the emerging market slowdown.

Chinese export and import statistics released this week confirm a slowdown. Exports dropped 5.5% Y/Y while imports declined 13.8%. A longer term view of both statistics shows a worrying trend. Let’s start with exports:

Exports always drop sharply in the first part of the year due to the Chinese New Year. Exports were flat for 2013 and the first ¾ of 2013. They rose at the end of 2014, but have returned to weaker levels in the last four readings. Imports raise more serious questions:

This year’s readings are down sharply, potentially indicating a deteriorating consumer demand scenario. Declining commodity prices could be responsible for some of the drop. However, it’s difficult to believe Chinese consumers haven’t taken a sentiment hit this year, especially with the Shanghai market’s volatility.

About a year ago, analysts argued the US and UK were in a race to see which bank would raise rates first. Low inflation has taken the BOE off the list, as they explained in their latest policy statement:

Twelve-month CPI inflation rose slightly to 0.1% in July but remains well below the 2% target rate. Around three quarters of the gap between inflation and the target reflects unusually low contributions from energy, food, and other imported goods prices. The remaining quarter reflects the past weakness of domestic cost growth, and unit labour costs in particular. Although pay growth has recovered somewhat since the turn of the year, the recent increase in productivity means that the annual rate of growth in unit wage costs is currently around 1% – lower than would be consistent with meeting the inflation target in the medium term, were it to persist. Additionally, sterling’s appreciation since mid-2013 is having a continuing impact on the prices of imported goods. A combination of these factors has meant that the average of a range of measures of core inflation remains subdued, although it picked up slightly in July to a little over 1%.

Above, the BOE argues the sources of low inflation are entirely situational; the bank simply has to wait for an oil price rebound and drop in the Sterling and inflation will move closer to policy maker’s 2% target. Most major central banks subscribe to this analysis which intuitively makes sense. But central banks have missed some major developments over the last 10-15 years and their current models continue predicting a higher inflation rate than the macro-economy is delivering.

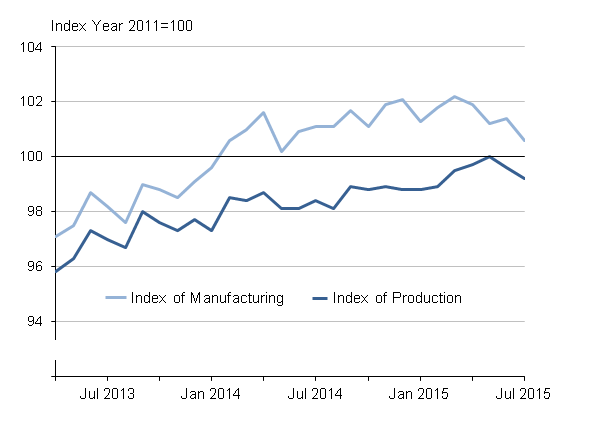

The last Markit manufacturing PMI report noted the strong sterling contributed to weaker manufacturing numbers over the last 6 months. The latest production and manufacturing numbers confirmed this slowdown: manufacturing dropped .5% Y/Y although production increased .8% Y/Y. This chart from the report shows manufacturing’s decline since 02/15:

This slowdown is another factor that is probably keeping the BOE on the sidelines for now.

The Bank of Canada maintained interest rates at .5% this past week. Their release contained the following observations about the Canadian economy:

Inflation has evolved in line with the outlook in the Bank’s July Monetary Policy Report (MPR). Total CPI inflation remains near the bottom of the target range, reflecting year-over-year price declines for consumer energy products. Core inflation has been close to 2 per cent, with disinflationary pressures from economic slack being offset by transitory effects of the past depreciation of the Canadian dollar and some sector-specific factors. The dynamics of GDP growth in Canada outlined in July’s MPR also remain intact. The stimulative effects of previous monetary policy actions are working their way through the Canadian economy.

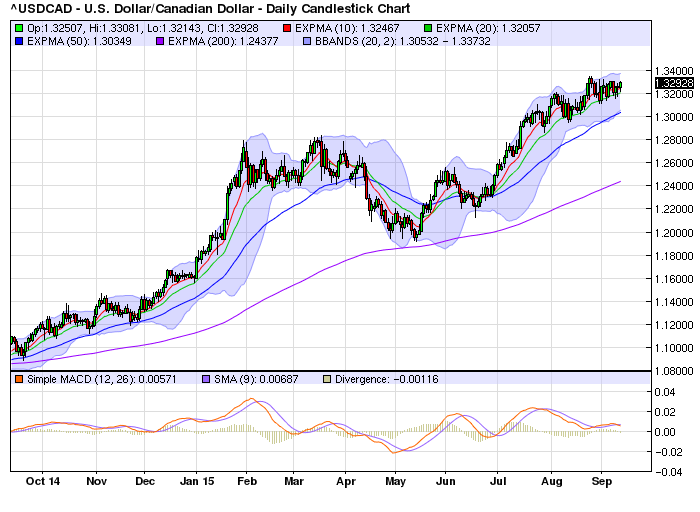

Like the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada’s statement implies the effects of low energy prices are transitory. But unlike England, Canada’s weaker currency is aiding inflation by increasing import prices. For example, the USD is up ~20% versus the CAD over the last year:

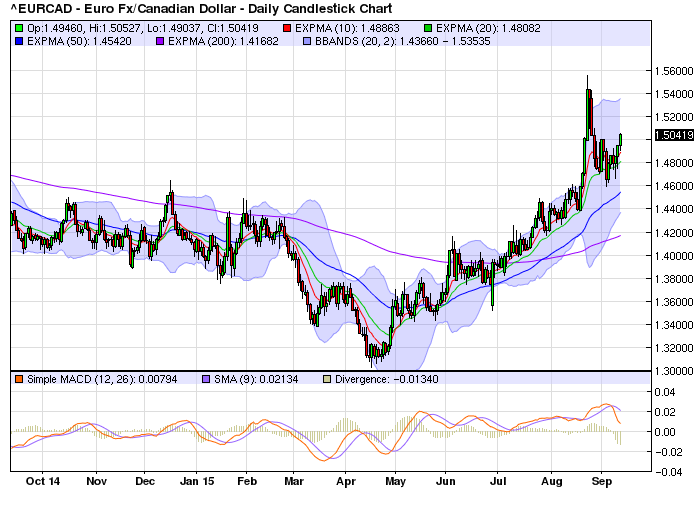

And the EUR increased a little more than 14% over the same time period:

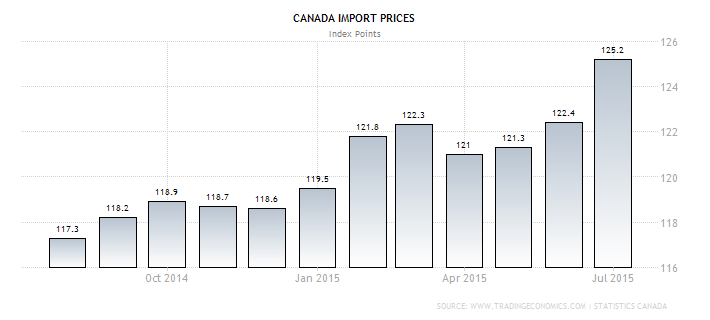

As a result, import prices increased ~7% over the last 12 months:

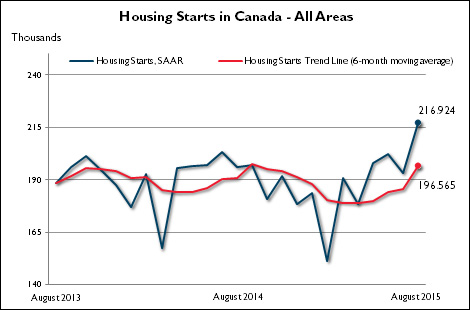

The Bank also noted its rate cut earlier in the year was working through the economy. The strong increase in housing starts in the latest release and over the last 6 months confirms this observation:

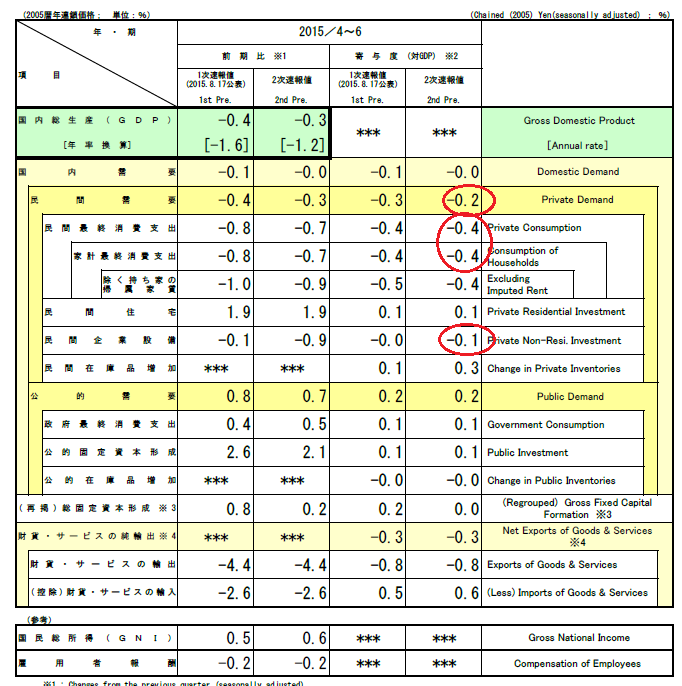

Japanese numbers continue to worry. Although authorities revised 2Q’s GDP higher, the economy still contracted at a 1.2% annualized pace. Household consumption contracted .4% Q/Q while private, non-residential investment decreased .1%. The .3% inventory and .1% residential construction increase were the sole positive private sector numbers.

And this week’s flash LEIs and CEIs declined .1% and 1.6%, respectively. Paul Krugman stated he was concerned about Abenomic’s potential success:

“I’m still really, really worried,” Krugman said at a conference in Tokyo on Wednesday. A big problem remains building enough momentum in the economy to escape deflation, he said.

Krugman said he is concerned that Abenomics is getting bogged down as the Bank of Japan fails to spur inflation to a 2 percent target, hampered by falling oil prices. The economy is struggling to rebound after a contraction last quarter, while the central bank’s main gauge of inflation fell to zero for a third time this year in July.

And other members of the Japanese government are calling for additional stimulus.

I'll cover US news in tomorrow's US Equity and Economic Review.

There has been a slight but important shift in news coverage over the last few months. It started with the wild gyrations of the Chinese stock market, which, in retrospect, granted journalists permission to write more negative stories about the global economy. Since then, we’re seen more discussion about EM capital flight, the fiscal troubles of Brazil and the potential issues related to Russia. The news is hardly catastrophic; it simply represents the natural ripples flowing out from China’s attempt to change its economic model and the potential Fed rate hike coming down the pike. But it is fundamentally changing the global economic model. The markets are reacting to this change by reallocating capital, increasing volatility. And considering China is still changing its model, we’ll probably see additional volatility in the coming weeks.