Insanity Rules

Bond markets are certainly displaying a lot of enthusiasm at the moment – and it doesn’t matter which bonds one looks at, as the famous “hunt for yield” continues to obliterate interest returns across the board like a steamroller. Corporate and government debt have been soaring for years, but investor appetite for such debt has evidently grown even more.

A huge mountain of interest-free risk has accumulated in investor portfolios and on bank balance sheets. Globally, more than $13 trillion in sovereign bonds trade at negative yields to maturity. In spite of soaring defaults, junk bond yields have collapsed again as well. In short, insanity rules in the bond markets.

A recent article in the FT informs us of “a wave of foreign demand for US corporate debt”:

Record-low interest rates are no barrier for US companies finding buyers for their debt thanks to a relentless global quest for fixed returns that shows little sign of easing. The pace of US corporate debt sales — which has not been fast enough to quench investor demand — is expected to continue unabated driven by foreign buyers in a world where roughly $13tn of sovereign and corporate debt trades in negative territory.

“It is a low return world,” says Ed Campbell, a portfolio manager with asset manager QMA. “You don’t have a lot of asset classes that are attractive and there is a flight to quality where the US is outperforming.”

More than $2.3tn of dollar-denominated debt has been issued by companies and banks since the year began, including three of the ten largest corporate bond sales on record, Dealogic data show.

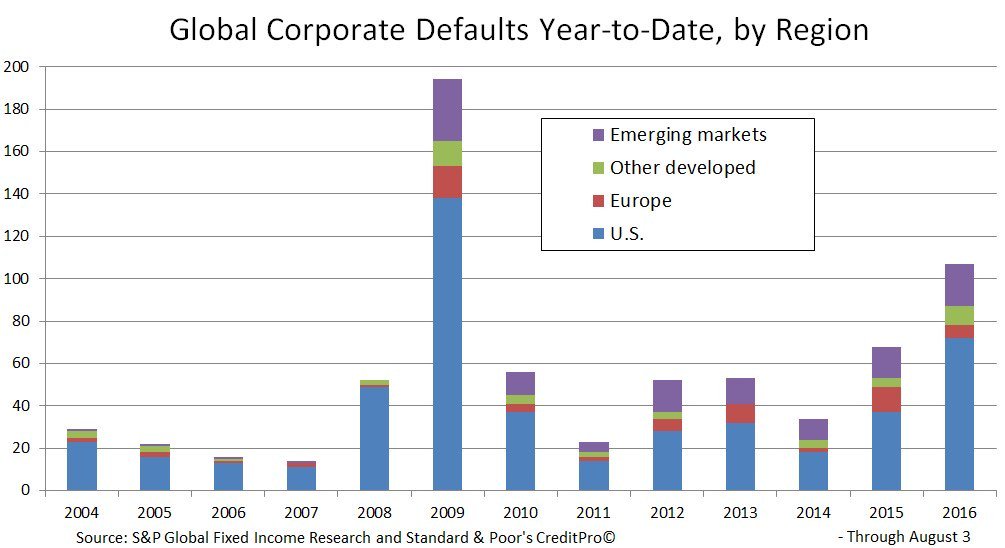

This not only shows that “investors” (we use the term loosely) are insane, it also happens to be a contrary indicator. Foreign buying of US assets very often reaches record highs prior to major financial accidents. Is this really a “flight to quality?” Corporate defaults are currently at the highest level since 2009, with US defaults clearly leading the pack:

Corporate defaults by region. Foreign investors are rushing into US corporate debt because – as one observer put it – “A yield of 2.83 per cent can fall a lot more than a [yield of] 0.71 per cent.” What more reason could one possibly need? – click to enlarge.

An Ominous Blurb

What prompted us to post this update on the situation was a little blurb that appeared in our email courtesy of Fitch:

U.S. HY TTM Default Rate Exceeds 5%; Energy YTD Defaults Tally $33 Billion

There was $5.2 billion of U.S. high yield bond default volume in July, pushing the TTM rate to 5.1% from 4.9% at the end of June

The market registered $39.9 billion of defaults over the past four months, with the energy sector comprising 67% of the total

The July energy TTM default rate reached 16% while the E&P sub-sector rate climbed to 31.2%

August already has $1.5 billion of probable defaults, including two more energy companies in their grace periods after missing interest payments

The high yield market saw solid activity, as there was $15.2 billion of July issuance, more than doubling the volume of the prior year

Energy accounts for $17 billion of the $78 billion of high yield debt maturing by December 2017

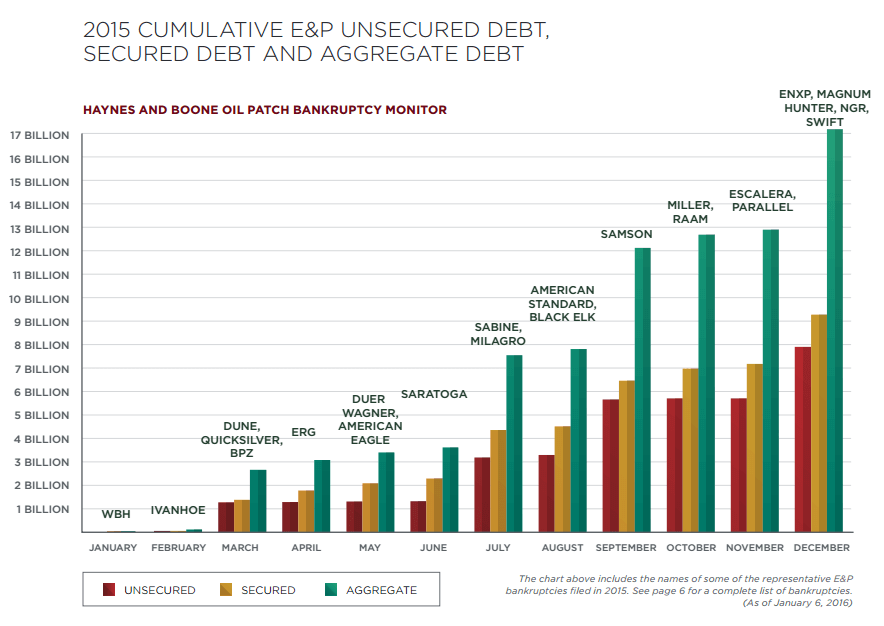

Naturally, the bulk of high yield defaults is still concentrated in the energy sector – but that hasn’t kept the energy sector from increasing its total debt load to a new record high. Apparently, investors haven’t received enough punishment yet… or maybe they are just masochists?

Cumulative debt defaults in the energy sector in 2015 (so far, the trend has continued in 2016). In spite of this, debt issuance by energy companies has just reached a new record high! – click to enlarge.

The FT inter alia quotes a number of market observers on the recent wave of foreign buying of US corporate debt. Note that not even the slightest trace of irony is detectable in these remarks, which is quite astonishing by itself:

“The reach for yield has morphed into a desperation for yield post the Brexit vote,” Nathaniel Rosenbaum, a credit strategist with Wells Fargo), says.

“You can feel this wall of money coming in,” says Stephen Kotsen, a portfolio manager with Nomura Corporate Research and Asset Management. “We are seeing flows from every region and every type of investor because of the central bank easing. That wall of money has to be put to work.” [TINA! TINA! TINA! ed.]

“What people are looking for is a little bit of yield [and] the chance of capital gains,” says Nick Gartside, JPMorgan) Asset Management’s fixed income chief investment officer, pointing to the difference between yields on European and US company bonds. “A yield of 2.83 per cent can fall a lot more than a [yield of] 0.71 per cent.”

Ah yes… why worry about tens of billions in defaults, when you can get that juicy 2.83% annual yield! To be fair, one of the pundits quoted in the article does mention that this mad rush into bonds harbors the potential for big losses at some point down the road (but of course, not yet).

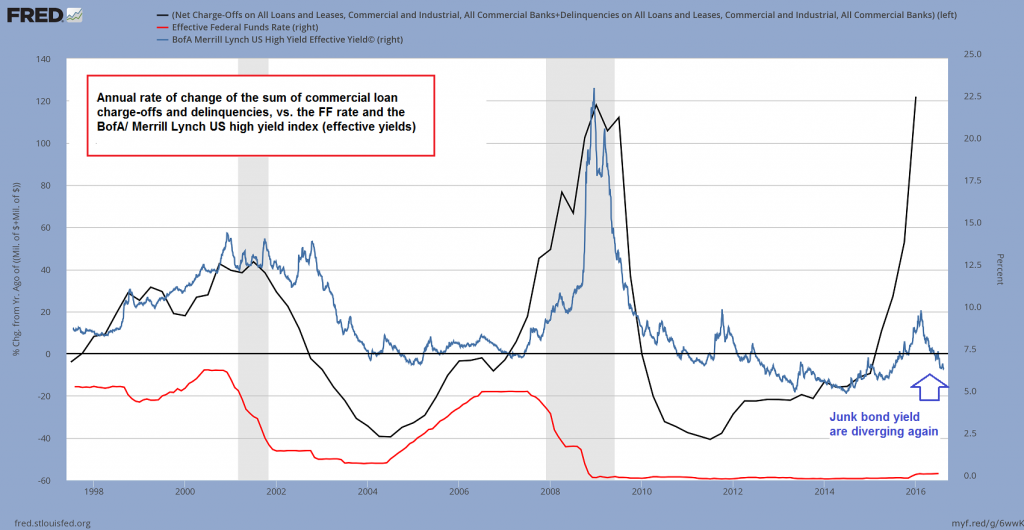

Ever since investors have become convinced that the Fed will remain on hold with respect to rate hikes and that even more central bank stimulus is on its way around the world, market distortions have intensified sginificantly. Consider for instance the divergence illustrated by the next chart:

The annual rate of change of the sum of commercial loan charge-offs and delinquencies (black line, lhs), US junk bond yields (blue line, rhs) and the FF rate (red line, rhs). Normally, junk bond yields and the rate of change of commercial loan charge-offs are very closely correlated. Most of the time junk bond yields are exhibiting a slight lag. An unusually large divergence is currently in evidence –

As an aside to the above chart (which we have shown previously, excl. the comparison to junk bond yields), it has come to our attention that it has apparently been misinterpreted by some people. The black line shows merely a rate of change – it illustrates how quickly loan charge-offs and delinquencies are growing relative to their level of one year ago. The fact that the pace of charge-offs has recently been even faster than in 2008/9 does not indicate that there are now more defaults than occurred at the time.

It is only telling us that loans are going sour very quickly, albeit from a very low base. Nevertheless, given the cumulative amounts of corporate defaults over the past 18 months (shown in the chart further above), the actual level of defaulting debt is slightly disconcerting as well by now.

Sovereign Bonds – Even Greater Risk?

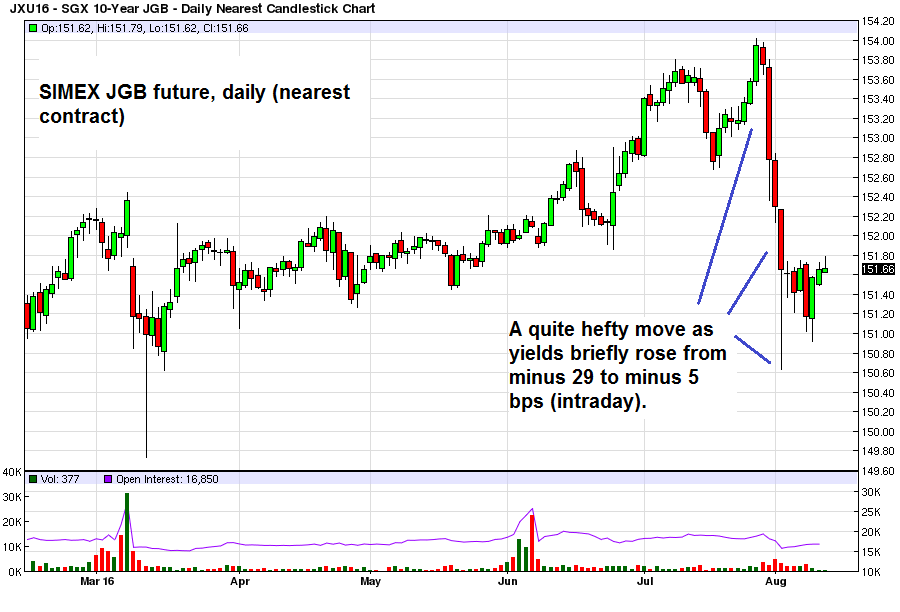

In the long run, investors in negative-yielding sovereign bonds may be incurring even greater risks. A reminder of the convexity effect at ultra-low and negative yields was provided by the JGB market two weeks ago, when yields moved from minus 29 bps to approx minus 5 bps intra-day in four trading days (current level approx. minus 11 bps):

JGB futures daily… yes, government bond prices can actually fall as well… – click to enlarge.

Anyone buying sovereign bonds at negative yields to maturity risks staggering losses should yields merely move back to the levels seen two or three years ago. Given that headline CPI is set to rise in the major currency areas on account of base effects alone (reflecting higher energy prices) we certainly wouldn’t rule out that something of the sort could actually happen.

Moreover, positioning in the bond market has reached an extreme. The net speculative long position in US treasury bond futures is currently at the highest level since the Russian crisis in 1998:

Net commercial hedger position in 30-year Treasury bond futures (the inverse of the net speculative position). Speculators positively hated the long bond in early 2006, when it still offered a respectable yield – but they love it now, at record low yields.

As we often point out, a large speculative net long position in futures markets is not a bearish signal per se – but it does mean that the market concerned is vulnerable. It not only reflects very one-sided sentiment, but will tend to exacerbate downturns if/ when major technical levels are taken out in a decline, as futures traders tend to use fairly tight stops.

European Banks and LIBOR

We have not yet had the time to comment on the EBA bank stress test in Europe, but most of our readers are probably aware by now that the test once again mainly seemed to serve propaganda purposes. In short, it was mainly an attempt to shore up “confidence”.

A recent study by Germany’s ZEW Institute has concluded that if one were to subject euro area banks to a more demanding stress test – this is to say, one that actually simulates tail-risk type crisis conditions – the big banks would have truly stunning capital shortfalls. This is a far cry from what the EBA reported (see also Mish’s discussion here).

We do have a few more things to add to the stress test results, but will do so in a separate post. For now let us just say that it had major flaws that to our mind basically invalidate its conclusions almost completely. This doesn’t mean that the data collected and published by the EBA are worthless – on the contrary, it is actually great to have them available. We are merely talking about the test as such, and the “everything is fine” message implied by its result.

Right after the publication of the test, European bank stocks went into free-fall again, but have slightly recovered since then. These stocks are very “oversold” in every conceivable time frame (e.g., Deutsche Bank (NYSE:DB) was recently down 90% from its 2007 high, Commerzbank (OTC:CRZBY) more than 98% and Italian zombie Monte dei Paschi (OTC:BMDPY) more than 99%), so a bounce almost had to happen at some point.

We believe the long-term losses in market capitalization almost speak for themselves.

EURO STOXX Banks Index – a small bounce over the past several days, but overall the chart still looks awful.

One reason why we mention banks and bank stocks here is the fact that sovereign bond yields and bank stocks are in a kind of negative feedback loop at the moment. Every time yields rise, bank stocks are actually getting a boost, as the market apparently figures that this will be positive for their currently extremely depressed interest margins.

On the other hand, we believe sovereign bond yields are inter alia so low because large investors are worried about bank solvency and the possibility of getting “bailed in” if they hold large deposits. Effectively, sovereign bonds are now treated as a kind of “cash substitute”. A bond with a negative yield to maturity is certainly no longer comparable to a traditional bond investment.

Presumably large investors figure that in the event of a crisis, they are more likely to get their money back if they hold government bonds rather than holding electronic deposit money with banks. Deposit money is largely uncovered and could evaporate into thin air due to bail-ins once the next crisis hits – and we think it is an almost apodictic certainty that there will be another crisis in the not-too distant future.

In other words, negative yields probably don’t really reflect low “inflation expectations”, but are inter alia mainly a reflection of the risk premium component embedded in sovereign bond yields. It has become deeply negative, simply based on a comparison with the risk that large deposits held with banks entail (we will have more in this in an upcoming discussion of interest rate theory and “trust money”).

In the meantime fresh trouble has emerged for banks in need of dollar funding due to upcoming changes in US money market fund regulations. US MM funds were hitherto the biggest buyers of USD commercial paper issued by European banks. They have essentially retreated from this market, and euro-land banks can no longer can rely on cheap funding from this source. As a result, LIBOR has exploded relative to other USD interest rates:

1 and 3 month LIBOR: interbank lending in USD in Europe is becoming prohibitively expensive compared to other USD rates.

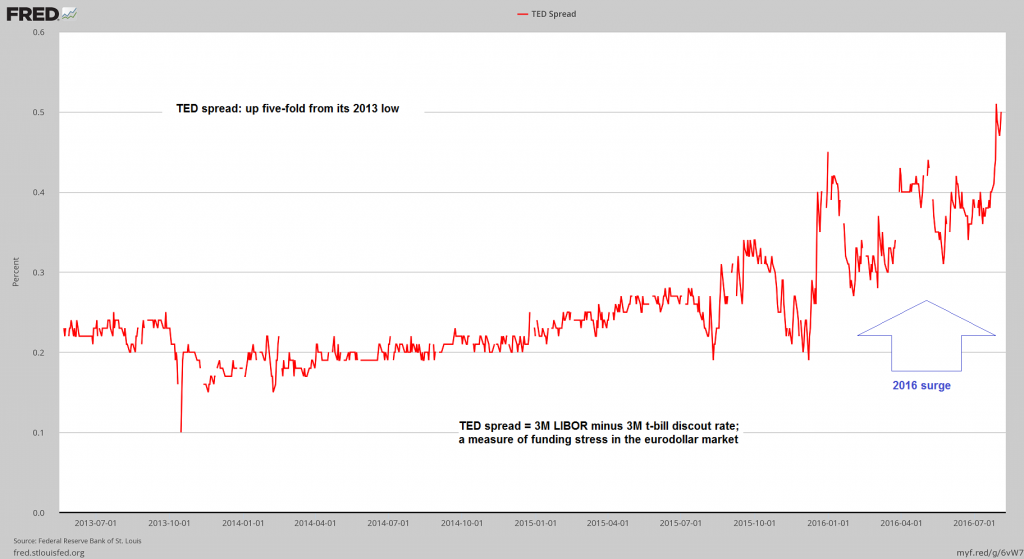

Euro basis swaps have plunged back into negative territory as well, and the TED spread also illustrates that this is becoming painful (always keeping in mind that we live essentially in a ZIRP world otherwise):

The TED spread has surged quite significantly – this is usually seen as a measure of funding stresses in the euro-dollar market, and the fact that it is allegedly “only” happening due to new MM fund regulations is surely cold comfort for the banks – click to enlarge.

Conclusion:

Distortions in financial markets keep growing, as central banks all over the world are desperately intensifying monetary pumping. What is currently happening in various bond markets as a result of this and other interventions is simply jaw-dropping insanity.

It is not so much that it defies rational explanation – in fact, all of these moves can be explained. What makes the situation so troubling is the fact that investors seem to be oblivious to the enormous risks they are taking. They are sitting on a powder keg.

A powder keg full with debt…

Charts by: S&P, Haynes and Boone, St. Louis Federal Reserve Research, StockCharts, BarChart, SentimenTrader, BigCharts