Much of the media is describing the Federal Reserve’s shift to tightening monetary policy, announced last week, as a pivot, which is a graceful word that sounds so much better than “botched call.”

Critics question whether there has been enough of a shift to address the problem of rapidly rising inflation. Even though the Federal Open Market Committee decided at its meeting to speed up its extremely slow tapering, it is still very slow, as the Fed continues to buy billions of bonds each month in the face of a sharp rise in prices.

Wall Street Journal editors even suggested that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell still believes inflation is transitory even though he won’t use the word after so much criticism.

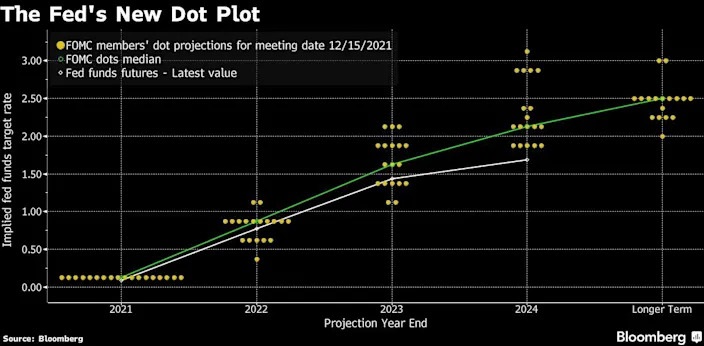

Those embracing the notion of pivot eagerly latched on to the dot-plot graph showing that a majority of FOMC members are now forecasting three rate hikes next year when not so long ago they saw none.

Source: Bloomberg

This is the dot-plot graph, part of the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) released every quarter, that Powell says we should not attach too much importance to.

The Fed has hardly covered itself in glory in 2021. Even if you are willing to consider that the shift announced last week to end bond purchases in March is a significant shift, it is painfully reminiscent of the about-face in 2019 when the Fed reversed its march to higher rates and gradually decreased the Fed funds target until COVID-19 hit and policymakers reduced it to near zero, where it has stayed.

Then-President Donald Trump bullied and scolded the Fed to change course and it duly happened, as the Fed admitted it perhaps had erred too much on the side of caution. Afterwards, the Fed changed its policy and said in the future it would not preemptively raise rates just because inflation is running hot.

The idea that 6.8% inflation is going to average out to a tolerable level above the Fed’s target of 2% is becoming almost laughable, whatever the putative gains in employment.

The notion that the Fed is politically independent is also falling by the wayside. By some strange coincidence, Powell’s pivot to a more hawkish stance, such as it was, came at the first policy meeting after he had secured the nomination to a second term.

There may be good reasons to keep Powell on, but it’s not because he’s doing such a bang-up job. Kevin Warsh, who was on the Fed’s board of governors from 2006 to 2011, was highly critical of Fed policy in an op-ed last week, blaming it for the current inflation:

“The risk of an inflationary spiral arises when policymakers first dismiss the problem and then cast blame elsewhere. Inflation becomes embedded in the price-formation process when the central bank acts belatedly or with insufficient conviction. To date, the Fed has acted as an enabler.”

Due Delibaration Or Erroneous Wait-And-See Attitude

Fed defenders say policymakers are acting with due deliberation as they recalibrate according to economic data. Typical is last week’s apologia from San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly, a longtime dove who now agrees that interest-rate hikes need to come next year, but insists that the Fed acted smartly and is now in a “good place.”

“The most important thing about being in a good place is you have optionality. And we will have the optionality to raise interest rates faster than the SEP currently says or raise them slower than the median on the SEP currently says or do just exactly what the SEP median says.”

Her argument is that a “premature” tightening of policy would have slowed down the economy—which of course is exactly what it is intended to do. The debate turns on when that measure is premature or timely.

Mickey Levy is a US economist who works for the New York capital markets unit of the German bank Berenberg. He says the wait-and-see attitude espoused by Daly and other members of the FOMC is a mistake because inflation will not go away by itself and requires immediate action.

“Supply bottlenecks have clearly pushed up prices, but robust growth in aggregate demand driven by excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus has been a primary source of inflation. The supply constraints will eventually dissipate. Policy makers can’t wait to tone down the bulging pipeline of monetary and fiscal stimulus.”

Levy is a member of the Shadow Open Market Committee, an independent group of economists which, as its name implies, stands in opposition to its official counterpart. Levy goes on to call for the FOMC to start raising rates at its next meeting, in January. “The stock market may fall in response, but delaying monetary normalization may undercut the sustainability of healthy economic growth,” he says.

The consumer price index for November hit 6.8%, the highest mark in 39 years, and the producer price index hit 9.6%, the highest on record. The data doesn’t indicate a good performance by the Fed in 2021 and doesn’t offer a rosy outlook for 2022.