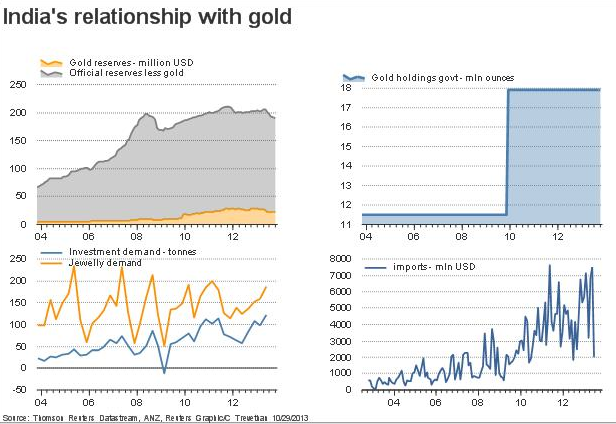

India is the world’s largest gold importer, consuming approximately 20% of global demand. As a result, changes in India’s imports (and it imports virtually all its consumption) can have a significant impact on gold price and supply.

Gold has a special place in India’s culture and society. Families and individuals keep gold as an investment and insurance against hard times. Temples and other religious bodies are also recipients of gold gifts, and over the generations, they have become significant holders of gold. So what? Nothing new in that position. Except the government, facing a worrying slide in the value of the rupee, a ballooning current account deficit, and a rising crisis of confidence in the Indian economy, is searching around for solutions.

The country’s total gold consumption is around 900 tons a year, two-thirds of which go into manufacturing and the rest into investments. Haresh Son, chairman of the All India Gems & Jewellery Trade Federation (GJF), was quoted in the Times of India, saying that the country imported 354 tons of gold in April-September 2013, of which 118 tons came in April, 162 tons in May, 31 tons in June, 41 tons in July, 2 tons in August and nothing in September.

The fall-off started with the threat — then implementation — of controls on imports, three tariff increases this year, and an 80:20 rule that dealers had to export 20% of what they imported as pure metal as finished jewelry. Illegal imports are estimated to have rocketed, as Indians won’t stop buying gold.

The government has been trying to tackle a growing current account deficit and a falling rupee. A surprise move on the part of Raghuram Rajan, the new governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), to raise interest rates has helped the rupee claw back some of its lost ground. The rupee tumbled to a record 68.845 against the dollar on Aug. 28 and was at 61.51 yesterday.

The RBI’s move was in response to fears that rampant food inflation would spill over into general inflation. The current account deficit widened to $21.8 billion in April through June from $18.1 billion in the previous quarter, the central bank said on Sept. 30. The gap was a record $87.8 billion in the year ended March 31 and prompted attempts by the government to curtail non-essential imports, the largest of which is gold.

by Stuart Burns