The personal consumption and expenditure (PCE) data for January surprised to the upside by printing a 0.4% surge in expenditures and a 0.3% increase in incomes. This was much stronger than the expected 0.1% increase of expenditures and 0.2% rise for incomes. The immediate assumption is that the consumer is healthy and the economy is growing but the "devil is in the details" as usual.

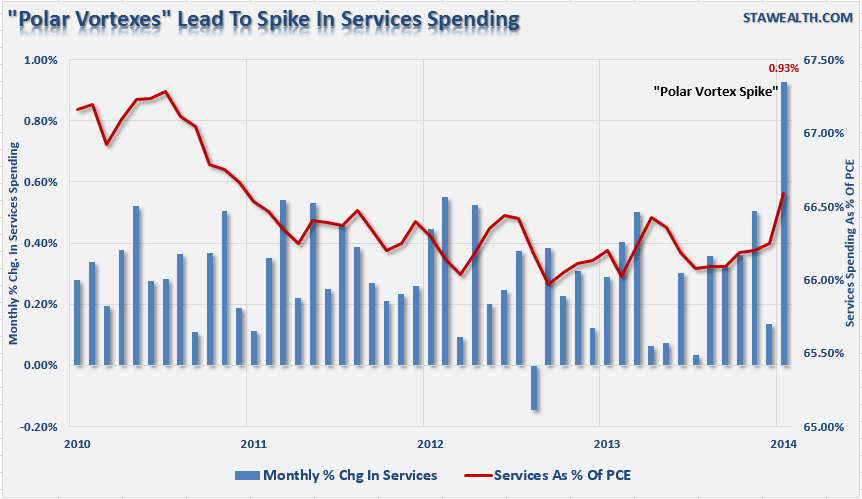

First, the impact of the extremely cold weather sent spending on utilities surging. This showed up as a sharp spike in "services" related spending to a record of $72 billion in the month of January. This increase also led to the fourth monthly decline in the personal savings rate to 4.3%, which is at the lowest level since March of 2013.

Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, validated this point stating:

"Excluding the 11.3% leap in real spending on utility electricity and gas — cold weather boosted demand for heating energy — real spending rose only 0.09%, compared to the 0.19% Q4 average. The core problem for consumers remains the sluggishness of real income growth, which rose 0.3% in January but fell 0.2% in December. The trend is running a bit below 2% at an annualized rate, and with the saving rate still very low at just 4.3%, it is hard to see scope for sustained gains in spending in excess of income growth."

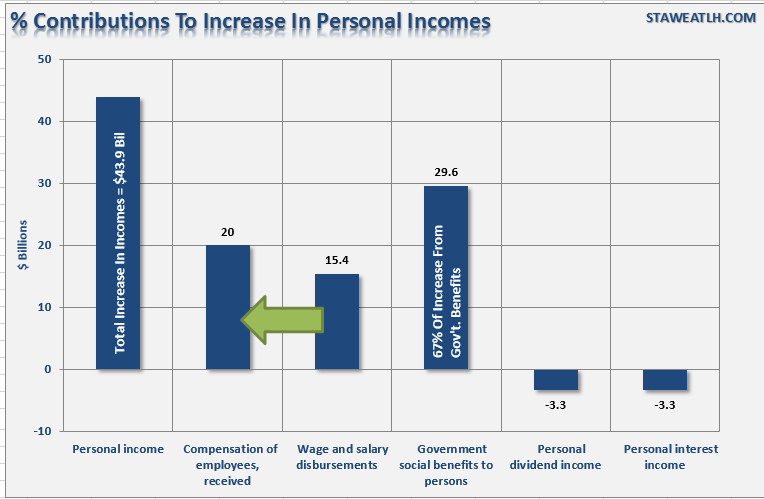

The problem of "real income growth" is the second point of this discussion. As shown in the chart below, more than 67% of the current increase in personal incomes came from "Government Social Benefits To Persons."

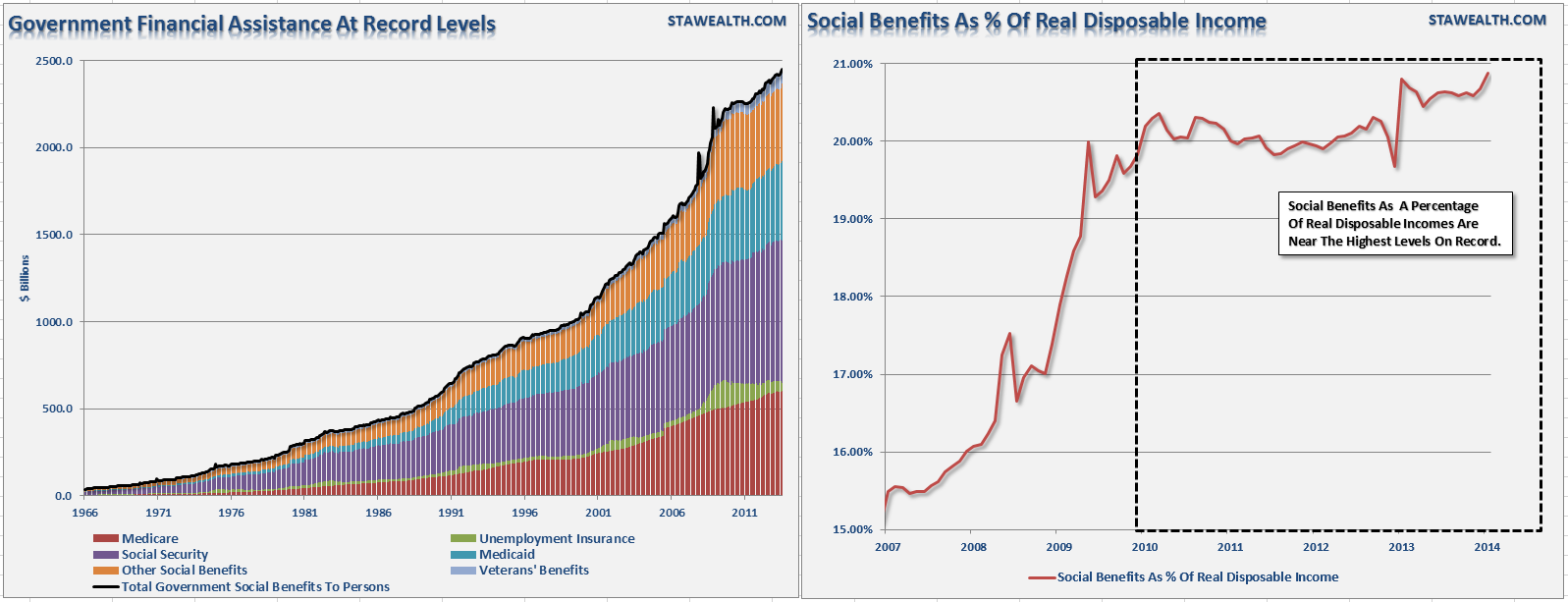

However, this is not a new phenomenon but an ongoing issue due to the long term deterioration of economic growth. The next chart shows both total government assistance, which is now at record levels, and social benefits as a percentage of real disposable incomes.

While personal incomes rose in January, they are not rising from underlying organic economic growth that is driving increases in employment and higher wages. Increases in jobs and incomes have primarily been a function of population growth rather than anticipation of accelerating economic expansion.

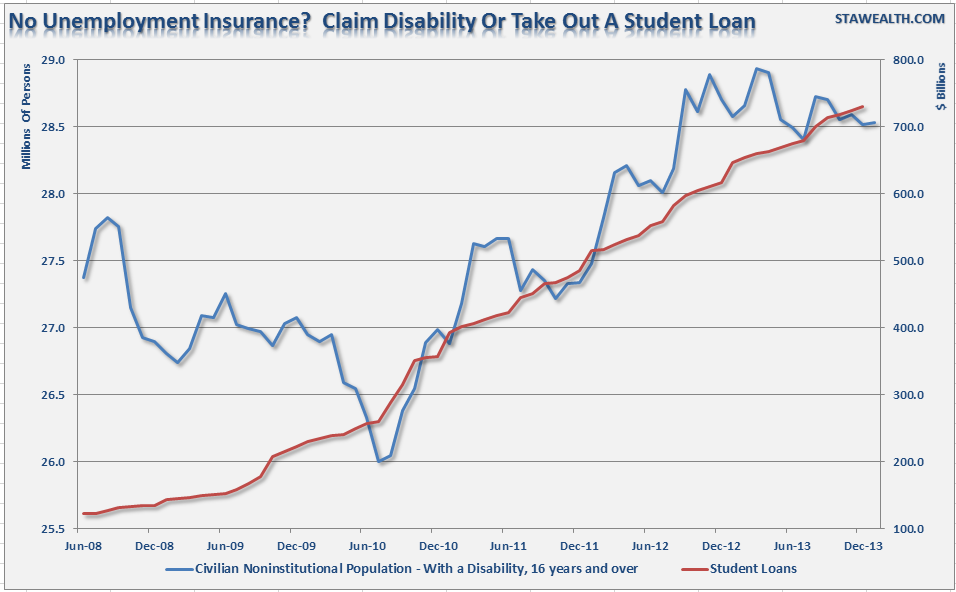

A couple of years ago I suggested that the surge in student loans was a function of individuals using them to maintain their standard of living (a cheap form of credit) rather than actually going to school. I posted the following chart previously which shows the rise in student loan debt and number of claimants on disability (which is also an easy form of welfare to qualify for.)

"However, if you cannot claim disability why not just say you are going back to school? Student loans have been hitting the mainstream media lately as the current administration debates the merits of lowering interest rates and forgiving student loan debt. We are told that we should pity the youth of America who are graduating college but so indebted that they can not service their debt or have a fair start at life. However, forgiving student loan debt when it wasn't used for education, but a new iPad instead, is another issue. Either I am correct about the real uses of student loan debt, or, we are about to embark upon the great educational renaissance."

I was chastised at the time for making such an "outrageous and insufferable" claim. Well, maybe it wasn't so outrageous after all, to wit from the WSJ:

"Some Americans caught in the weak job market are lining up for federal student aid, not for education that boosts their employment prospects but for the chance to take out low-cost loans, sometimes with little intention of getting a degree."

The problem for American families today, despite media commentary to the contrary, is simply the inability to maintain their current standard of living. The dichotomy between economic statistics and family budgets is stark. When there is an unusual disruption due to "polar vortexes" that sends utility costs skyrocketing, the increased spending boosts economic statistics. The reality for a family budget is quite different. For individuals they did not consume more gasoline when prices spike, they just pay more for the same amount of product. The same is true when there is an unusually cold winter which causes utility costs and usage to rise. These increases in costs are not necessarily a function of choice, but in some cases a matter of survival. Unfortunately, when incomes are primarily stagnant due to job loss or reduction in pay, the impact on families budgets is significant. Families must then make difficult choices about consumption or turn to debt to supplement the shortfall. The recent surge in consumer debt shows this to be the case.

These financial strains are pervasive and continue to weigh on families and their relationships. While it is true "money can't buy happiness," try asking a couple who are living on food stamps and working two part-time jobs to "get by" just how "happy" they are? Even as the media trumpets that the Fed has saved the economy from a "depression," it might just be a statistical victory at best. The government may say this is not the 1930's where bread lines formed outside the corner soup kitchen, however, for many American's the only difference is that those subsidies are found at the mailbox and online instead.