Activist hedge fund manager Bill Ackman succeeded in 2013 in ousting Procter & Gamble's (NYSE:PG) CEO Bob McDonald. It was noteworthy at the time because the company issued a strange memo repeating often verbatim answers to questions it posed to itself. Among them was if Mr. McDonald was fired or, as had been relayed publicly, he voluntarily retired. The memo merely thanked him for his 33 years of service and “notes the Company’s improving business performance.”

He was replaced by the man who picked him to be his replacement. A.G. Lafley was P&G’s CEO from 2000 to 2009. He turned over control in the executive suite to McDonald who was groomed for years by Lafley. It was then a largely uncontroversial succession.

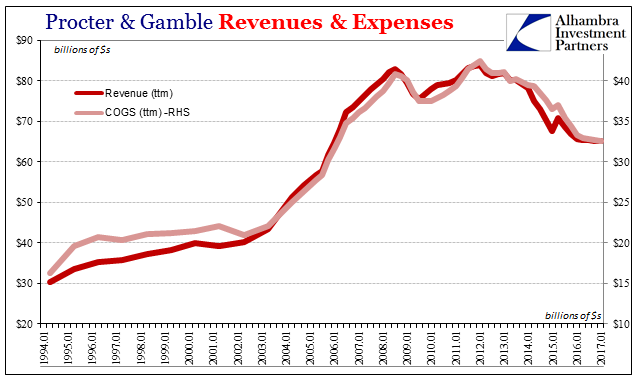

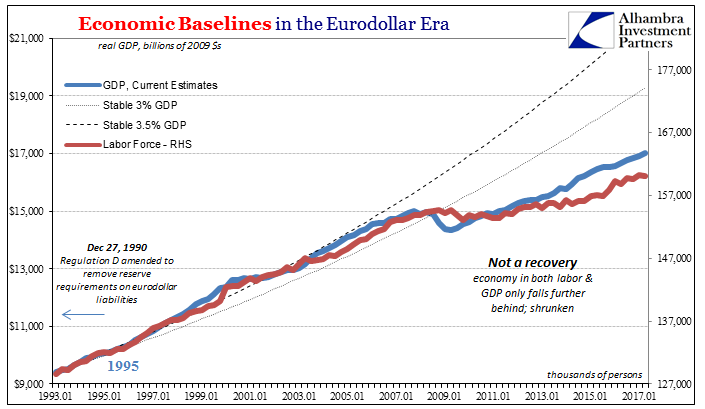

In 2012, however, McDonald was forced to undertake a massive cost reduction effort. The company aimed to reduce spending by $10 billion between that time and 2016. It had become apparent that growth in the developed world had stalled, an outcome that wasn’t supposed to happen so long after the Great “Recession.” Whereas recovery was thought to be literal, it took a very real detour around 2011.

Not only would P&G turn toward managing costs, it would also try to rebalance its business toward emerging markets. The company was already taking about 30% of its sales from those regions at the time, and it wanted more as a way to get out of the US/Europe rut. As McDonald said in June 2012:

We are making the necessary adjustments to our growth strategy to increase focus on our core business and to achieve more balanced growth across geographies, product categories and the top and bottom lines.

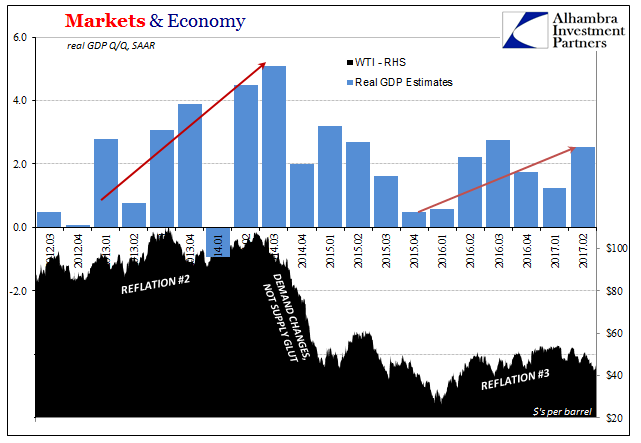

It was, of course, the exact wrong time to be transitioning in that way. Emerging market economies long thought immune to the kind of growth slowdown then plaguing the developed world would starting in 2013 experience one. The “rising dollar” that followed would not only wallop these economies, it would make financial translation of revenues and profits derived from them hugely unfavorable.

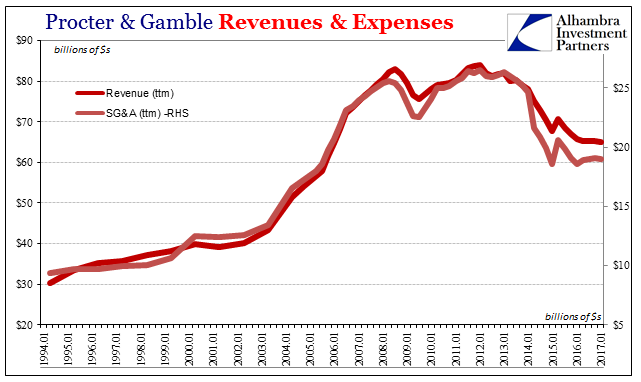

So in July 2015, amidst “unexpected” global turmoil, Mr. Lafley was allowed to retire a second time. And for the second time in six years he would be replaced by a P&G executive he had mentored for years. David Taylor was named CEO, and less than a year into his tenure he had announced a second $10 billion cost-cutting program (the first only achieved about $7 billion of the planned reductions).

When Taylor replaced Lafley, revenue at the global consumer products giant was considerably less than when Lafley replaced McDonald. Despite being six years after the official end of the Great “Recession”, revenue was lower in mid-2015 than at the worst of the global contraction in 2009. As of the latest earnings report, in 2017 sales are lower still.

What other choice does PG’s management have? It hasn’t seen sales growth really since 2008. There was a small recovery, mirroring the global economy at large, but only up to 2012 where it all fell apart almost everywhere around the world (delayed by “dollars” in EM’s). There was no longer any place to hide, no special region from which to magically capture revenue growth. It was, as PG and its open door management condition witnessed, all risk with very little return.

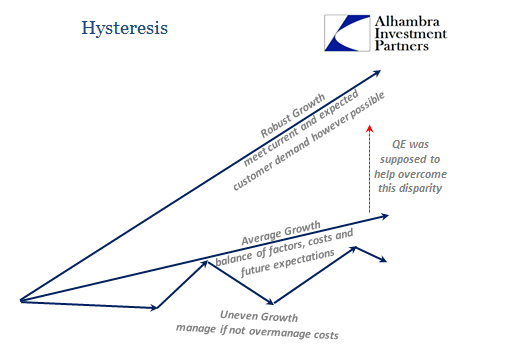

In times of topline advance, companies focus on managing growth; are we able to produce at a rate consistent with demand? Are we undertaking the proper growth strategy? When there is no revenue growth, the bottom line is scrutinized to an unhealthy degree (from a macro perspective). An on individual basis, it cannot be any other way since profit growth remains the central goal. For the economy, it’s a trap.

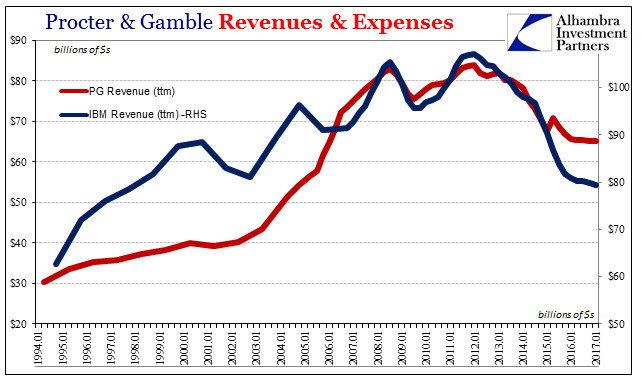

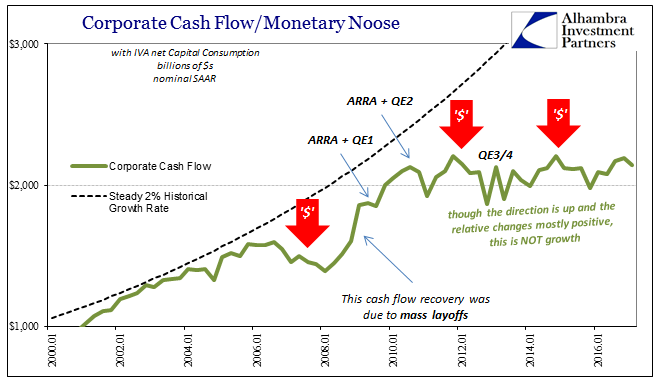

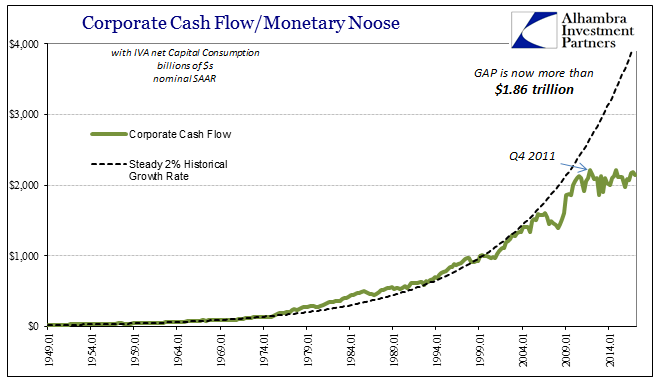

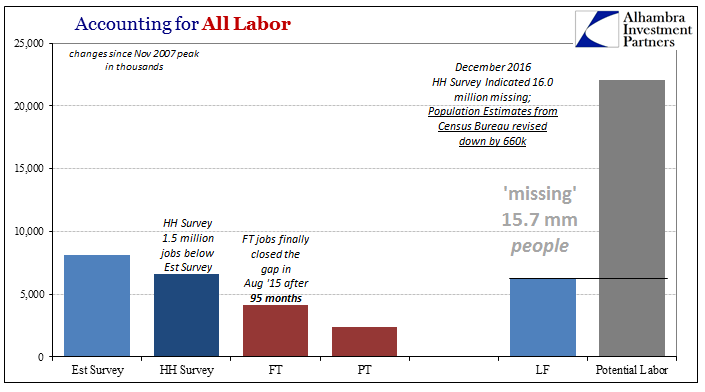

If Procter & Gamble was just some unique anecdote like IBM (NYSE:IBM) or Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO), a dinosaur (they say) being passed by the capitalist advance of innovation and sustainable evolution then we might not care that Big Blue’s revenue chart is far too much like PG’s. They are not isolated cases, however, far too representative of the actual economy. By any standard economic measure, especially corporate cash flow, we can appreciate the labor participation problem (either in the US fashion, or Europe’s) in a way that has nothing to at all to do with Baby Boomers or opioids.

It is an economic climate far worse than even the massive contraction of late 2008/early 2009. That one was at least temporary, or thought to be. This downturn or slowdown is relentless and never ends, and even the most reluctant business has had to come to terms with it. Sure, it changes here and there from somewhat negative to somewhat positive, but it never attains momentum that might allow companies like PG or IBM to go back to growth; and these are real businesses that put in tangible statements what might be otherwise left to a limited sense of proportion to what is really going on.

These are more than just government statistics, they are very real circumstances where tomorrow can only include the next multi-billion dollar cost cutting scheme. The media can talk about a labor shortage all it wishes, but PG, IBM, and calculated wage gains show that there is no such thing. Corporate America is in no rush to hire anyone but the executive with the strategy for the leanest.