One of the most important trends underway in North American energy markets has been the shift of drilling activity to fields rich in oil and natural gas liquids (NGL) from plays that primarily produce natural gas. Robust drilling activity in these liquids-rich plays explains why US natural gas production has remained resilient, despite depressed prices that render output from many fields uneconomic.

When exploration and production companies flow raw natural gas from a well, this stream often contains a number of other hydrocarbons and impurities. For example, some gas fields also contain large quantities of carbon dioxide, while wet-gas plays hold large quantities of NGLs such as ethane, propane and butane. Dry-gas plays, on the other hand, contain little or no NGLs.

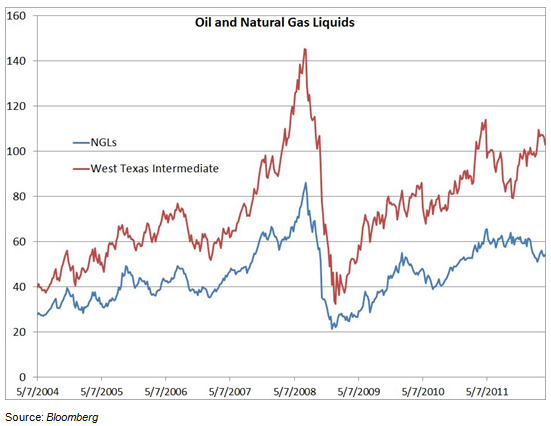

The price of a mixed barrel of NGLs historically has followed crude oil prices far more closely than the price of natural gas.

This graph depicts the price of a mixed barrel of NGLs that includes ethane, propane, butane and iso-butane and the cost of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil. Prior to mid-2008, a mixed barrel of NGLs usually traded at about 60 percent to 70 percent of the market value of a barrel of crude oil.

Recently, however, this relationship has broken down. In spring 2011, for example, the price of oil spiked because of the outbreak of civil war in Libya and concerns about supply disruptions resulting from the Arab Spring uprisings. Although NGL prices remained firm, they did not participate in the rally. NGL prices have declined slightly in 2012, whereas oil prices have moved higher.

The price relationship has deteriorated because of increased domestic production of NGLs. With natural gas prices hovering around depressed levels, producers have ramped up drilling activity in NGL-rich plays to improve wellhead economics.

Key liquids-rich plays include the prospective Eagle Ford Shale in southern Texas, the ethane-laden Marcellus Shale and the Granite Wash in the Texas Panhandle and Oklahoma. Oil-centric fields such as the Bakken Shale in North Dakota and the Permian in West Texas also produce meaningful volumes of associated natural gas and NGLs.

Rising NGL production accounts for the slight decline in the price of a mixed barrel of NGLs, while the strength of oil prices reflects a tightening global supply-demand balance and geopolitical risks to supplies. For these reasons, NGL prices haven’t responded to recent fear-induced spikes in oil prices.

That being said, the price relationship between NGLs and oils hasn’t completely broken down, in part because NGLs are widely used in the petrochemicals industry as a substitute for naphtha and other crude-derived feedstock.

At the same time, the US also has significant capacity to export propane and chemicals produced from NGLs, a release valve that the North American natural gas market currently lacks. Exports allow NGL producers to take advantage of much higher prices and tighter supplies in international markets.

Recently, a mixed barrel of NGL has traded at 45 percent to 55 percent of the cost of a barrel of WTI–less than the long-term average of 60 percent to 70 percent. With oil prices at elevated levels, NGL prices remain at levels that generate solid returns on investment.

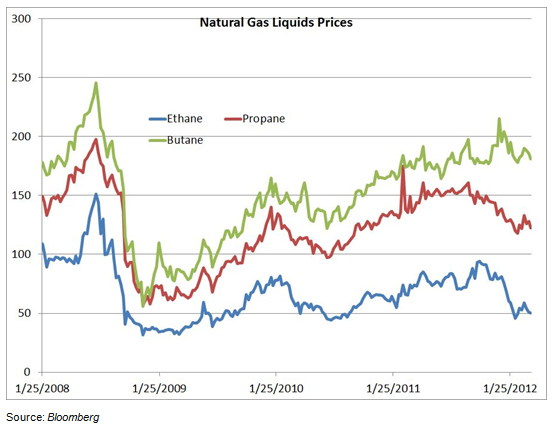

Also, the cost of a barrel of mixed NGLs obscures pricing trends affecting individual hydrocarbons.

Whereas the prices of heavier NGLs such as propane and butane have climbed with oil prices, ethane’s market value has come under pressure. Ethane is the lightest and most common NGL, making up as much as three-quarters of the total NGL volume produced from many natural gas fields. Much of this ethane goes to the petrochemical industry, which uses the NGL to create ethylene, a base chemical used to make some forms of plastic.

During conference calls to discuss last quarter’s earnings, analysts often asked about the extent to which weaker NGL and ethane prices would weigh on distributable cash flow. At this point, the downside risks for strong NGL-levered energy stocks remain modest and manageable.

The business that’s most likely to be impacted by weaker NGLs prices is gathering and processing. Gathering systems consist of small-diameter pipelines that collect oil, natural gas and NGLs from individual wells and transport these hydrocarbons to gas-processing plants. These facilities separate natural gas from NGLs, while fractionation plants isolate the mixed NGLs into individual hydrocarbons.

The gathering business would suffer from a reduction in drilling activity; fewer new wells to hook up to the system translate into fewer volumes to transport. But most MLPs that own gathering systems have reported little change in the long-term trends for this business. Producers have reduced their activity in dry gas plays and relocated rigs to oil- and NGL-rich basins, a trend that continues to benefit MLPs with assets located in liquids-laden plays.

For example, MLPs that own gathering systems in the Granite Wash have benefited from an upsurge in drilling activity and NGL production. Consider these comments from Joseph Mills, CEO of Eagle Rock Energy Partners LP (NSDQ: EROC) during the MLP’s Feb. 23 conference call:

In terms of the producers I would tell you that we’ve not seen anybody slow down the drilling activity based on this commodity price environment. I’ll say some of the operators that we service are big players that have natural gas exposure in other areas. And so we are concerned about – the hope is that they are going to redirect more capital to the Granite Wash. Some have balance sheet challenges. So we’re not sure if they’re going to be able to direct a whole lot more capital.

Eagle Rock Energy Partners’ management team also noted that capacity utilization rates at its processing facilities in the region continue to exceed 90 percent. However, Mills also indicated that producers with exposure to natural gas prices may not be able to raise the capital to accelerate activity in the Granite Wash to the extent previously hoped. This is only a modest headwind.

The processing business is tougher to analyze. Demand for processing tends to be hinged on the so-called frac spread, or the price of natural gas relative to the value of NGLs. When NGLs prices are high relative to the price of natural gas, demand for processing increases. That’s because producers want to remove every possible barrel of NGLs from their raw gas streams to take advantage of higher liquids prices. Although ethane prices have fallen and NGLs haven’t fully participated in the rally in oil prices, the price of natural gas has plummeted–frac spreads continue to hover at historically high levels.

Processors are compensated for their services in a number of different ways, including simple fees based on the volume processed or percent-of-proceeds (POP) arrangements where they receive the value of a portion of the gas and NGLs sold. The latter type of contract would benefit from still-attractive NGLs prices.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

How Will MLPs Fare With Weaker NGL Prices?

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.