“Of course there are true copper bottomed mistakes, like spelling the word “rabbit” with three m’s, or wearing a black bra under a white blouse, or, to make a more masculine example, starting a land war in Asia.” — John Cleese

We all make mistakes, but some are bigger than others. An example of a serious one that’s both potentially catastrophic and easily avoided is to lend money for long periods during a time of rising debt and financial instability.

Who, for instance, would commit capital for 30 years to Italy by buying that country’s long-dated government bonds? “No one” is the sane answer, yet those bonds do find buyers.

Even higher on the crazy scale is the following:

Ireland Sells First 100-Year Bond, Staying on Comeback Trail:

Ireland sold its first so-called century bond, less than three years after it regained economic sovereignty by exiting an international bailout program.

The nation’s debt office sold 100 million euros ($113 million) of the securities at a yield of 2.35 percent. By contrast, investors are demanding a yield of 2.66 percent to lend to the U.S. government for 30 years.

With the nation in the midst of commemorating the centenary of the 1916 rebellion that eventually led to Ireland’s breaking from the U.K. in 1922, Ireland is seeking to lock in lower borrowing costs amid the European Central Bank’s unprecedented stimulus. Last year, Mexico sold the world’s first 100-year government notes in euros.

The sale “is both a testament to the restored confidence markets have in Ireland’s creditworthiness, as well as a sign that duration- and yield-hungry investors are looking to extend to the max along the curve,” said Owen Callan, a fixed-income strategist at Cantor Fitzgerald LP in Dublin.

Irish borrowing costs have plunged since it exited an international bailout at the end of 2013, aided by a recovering economy and ECB President Mario Draghi’s pledge to do whatever it takes to save the euro.

The yield on Ireland’s benchmark 10-year bonds peaked at 14.2 percent at the height of its crisis in 2011. The yield on the securities has since fallen to below 1 percent and was at 0.73 percent as of the 5 p.m. London close.

The ECB has begun a second year of buying sovereign debt, part of a stimulus plan that includes imposing negative deposit rates for banks, which have served to crush yields across the eurozone. In Germany, bonds maturing in as long as eight years have yields below zero.

In December, the debt office said it would seek to sell 6 billion euros to 10 billion euros of bonds in 2016. Wednesday’s sale was by private placement through Goldman Sachs and Nomura Holdings.

“This ultra-long maturity is a significant first for Ireland and represents a big vote of confidence in Ireland as a sovereign issuer,” Frank O’Connor, the Dublin-based sovereign issuer’s director of funding and debt management, said in an e-mail statement.

A few questions

If you’re a “yield-hungry” investor, what do you gain with a bond that returns 2.35%? By any historical measure that’s ridiculously low. The average bank savings account had a higher return for the 50 years following WWII.

And since institutions like pension funds and insurance companies as well as individual retirees have based their plans on projected returns two or three times this high, owning such bonds doesn’t make these entities any more viable.

So let’s go with “who the hell knows?” as the only reasonable answer to the above question.

Meanwhile, if you’re “duration hungry”, how does locking in a low rate for a longer time help you match your book — that is, line income streams up with obligations so that when the latter come due the former are guaranteed to be there? What obligations both run for a century and can be predicted with anything other than simple extrapolation (which is to say pure guesswork)?

The answer is that there are none. Sure, pension funds and insurance companies might need to pay out benefits in 2116, but they also might have long since been replaced by an artificial intelligence that meets the needs of its human slaves without recourse to archaic concepts like money. So planning for something that distant and nebulous is silly.

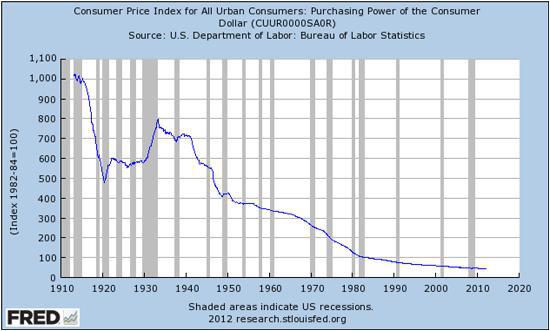

And the big one: Who in their right mind would tie up money for five years in this world, let alone 100? Here’s a chart of the dollar’s value over the previous century:

Remember that this is the best currency. Most others have lost even more value. And this decline happened when global finances were far, far stronger than they are today.

Had you bought 100-year bonds in, say, 1920 you might still be getting paid, but in 95% cheaper dollars. And your principal would be so diminished as to be hardly be worth considering.

Going forward, even economists who think the global financial system is fixable define the fix as a burst of inflation that allows debtors to pay their interest in cheaper currency.

A 4% inflation rate achieved through sustained currency devaluation would make today’s 100-year bonds the platonic ideal of a bad investment. And that’s the best case scenario — all the others involve extinction-level events for financial assets.