Part of the reason China’s economy has slowed is as a result of deliberate policy actions taken by Beijing to steer it from investment-led, export-orientated manufacturing toward a model based much more on domestic consumption.

The result has not been great for resource companies or economies around the world, but it will, in the long run, be a more sustainable model for China, and indeed for the world. China’s super-cycle was unsustainable in the medium- to longer-term, the sooner it was curtailed the lower the long-term fallout was likely to be.

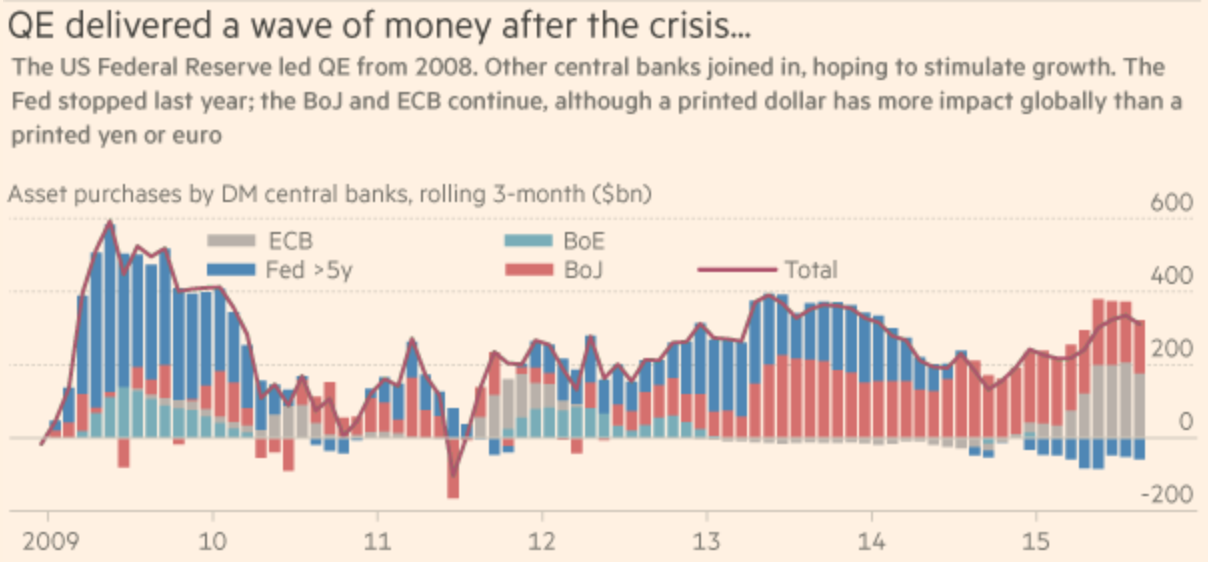

But there is another reason investment growth has slowed, not just in China but in virtually all emerging markets and that is because the US and other mature economies have on the whole reined in quantitative easing.

An article in the Financial Times states that as the Federal Reserve has purchased US treasuries, driving up bond prices and driving down yields, banks and pension funds have taken low-cost loans from recipients of those treasury sales — the banks — and invested them in higher-yielding assets, mostly corporate emerging market debt.

Emerging Markets

By some measures, the article says $7 trillion of quantitative easing dollars have flowed into emerging markets since the Fed began buying bonds in 2008, and that is before adding in QE from the UK, Japan and, more latterly, the European Central Bank. The FT quotes Andrew Hunt of Andrew Hunt Economics when it seeks to explain where those funds have gone and the impact all that loose money has had on emerging market debt levels, and I quote in part as follows.

How QE Money Gets To Emerging Markets

There are two main routes by which QE money reached emerging markets. One involved the Fed buying US treasury bonds, as outlined above, which results in savers going in search of higher yields — such as in mutual funds buying corporate and emerging market debt.

But Hunt estimates that although this is the effect most people focus on, it is in reality of less impact than the second route which involves the cash paid for treasuries going in search of higher yields to hedge funds and other investors.

How to Leverage QE Dollars

Hedge funds and so-called leveraged funds often use these loans to buy money-market instruments in the Singapore dollar, Philippine peso or Brazilian real, for example, in order to earn a higher yield. On this route, which Mr. Hunt believes is more widespread, some QE money would be multiplied before leaving the donor country: a leveraged fund might take $10 in cash, borrow another $30 and invest $40 in an emerging currency.

Some of it would not be leveraged, but all the money on this route is taking part in the “carry trade:” borrowing in currencies where interest rates are low and investing the proceeds where they are high. This works while exchange rates are favorable — but can go wrong when they change as has happened this year.

As this cash flows out to emerging markets, their central banks buy it up to prevent their own currencies appreciating and, in so doing, print cash as a liability to counter the asset these foreign deposits on their books represent.

Where Does This Cash Go?

Into the local banking sector almost forcing local banks to lend more. Banks are not the only lenders big, emerging-market companies have been issuing foreign currency bonds to, to take part in carry-trade lending into the “shadow” banking sector for higher yields.

Source: Financial Times

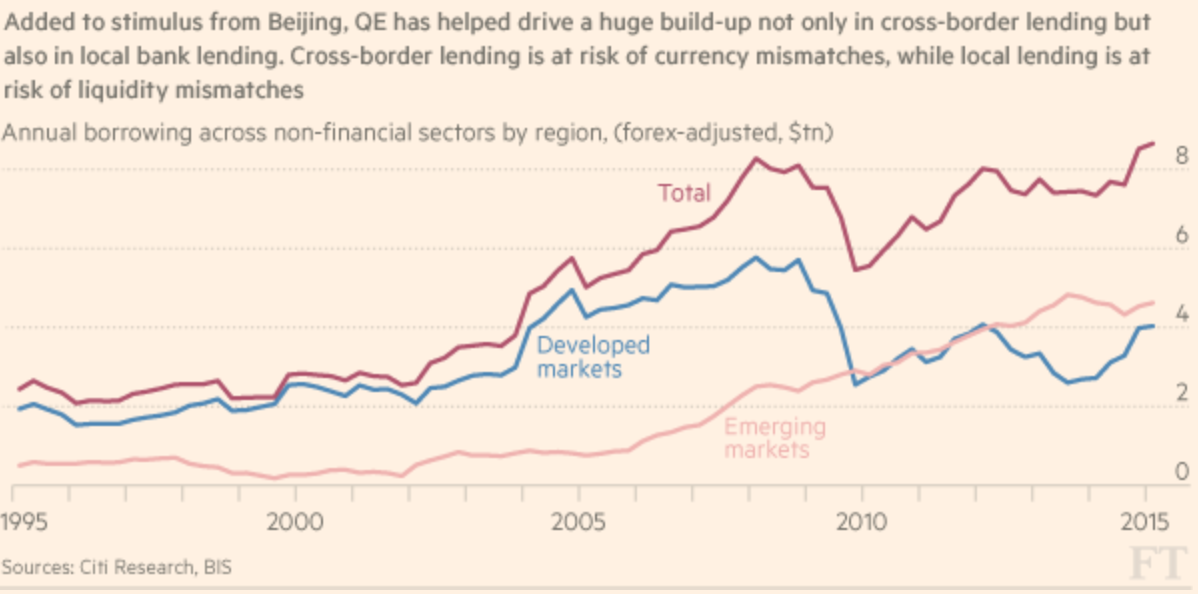

Taking on debt for productive investment is, invariably, a positive process but the article contends that, in far too many cases, that is not what has been happening.

The Bank for International Settlements looked at leverage and profitability at 280 big emerging-market corporate bond issuers. They found that while leverage at those companies was up, profitability was sharply down.

The Problem With Carry Trade Investments

As profitability decreases and repayments on foreign denominated debts increases, corporates are likely to withdraw funds, thus reducing liquidity in the banking system. Last week, the Institute of International Finance said bank lending conditions in emerging markets (a broad measure that includes credit demand, availability and non-performing loans) had deteriorated sharply, with some measures at their worst levels since the IIF began monitoring conditions in 2009, the FT reports.

Quoting the IIF’s managing director, who said emerging market companies are finding it harder to repay their debts and harder to raise new money for investment, putting further downward pressure on growth. This not only contributes to the slowdown, but reduces the chance of an early recovery.

The risk, the FT suggests, is not of a full-blown emerging market crisis, but of heavily indebted companies, and partner banks exposed to them, as they fall into a vicious circle of low profitability, higher non-performing loans and tighter credit conditions.