There is little argument that the economic data has been "weaker than expected" with the reason being quickly attributed to "the weather." This has particularly been the case with regard to the recent housing data which has put a dent into the "housing recovery will drive future economic growth" story. However, is the reason for the weakness in housing really just a "weather" related story? Let's take a look at the data to make a more informed determination.

When the mainstream analysts and economists discuss housing data it is generally on a seasonally adjusted and annualized basis. For example, in January of this year we were told that on a "seasonally adjusted basis" the number of New Housing Starts was 880,000, this number was down from December's total of 1.48 million. However, 880,000 homes were NOT started in January but rather just 59,100 which is a much less exhilarating number. However, this is where the fun with numbers begins.

In order to get from 59,100 to 880,000, the U.S. Department Of Commerce assumes that 59,100 homes will continue to be built each month throughout the remainder of the year. Therefore, 59,100 new homes are multiplied by 12 months to get a total of 709,200 new homes on an "annualized" basis. However, the "fun with numbers" doesn't stop there. The 709,200 new homes is assumed to "be low" because January months are ALWAYS impacted by inclement weather which suppresses building activity. Therefore, the number of new homes is adjusted upward by 170,800 to account for the impact of "weather related conditions."

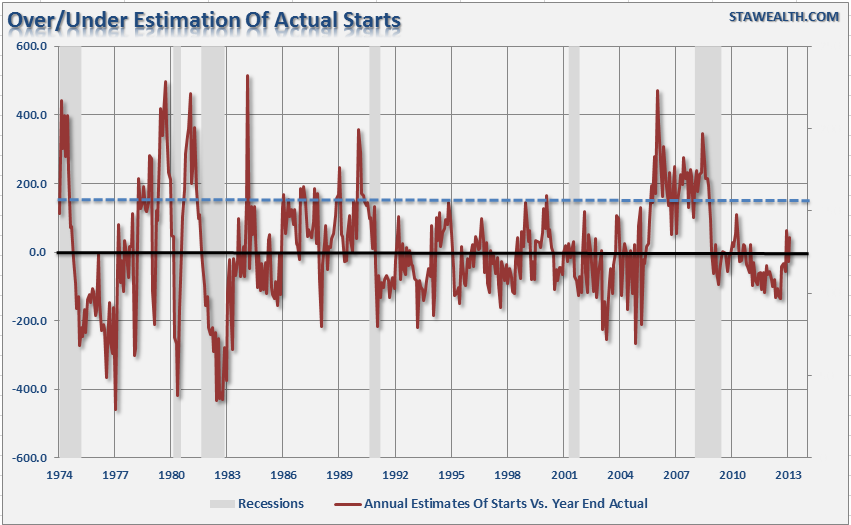

Let's take this one step further and look back 12 months ago at new home starts in February of 2013. At that time, it was reported that 969,000 homes were started on a seasonally adjusted and annualized basis. That number was derived from an actual number of starts of 66,100 multiplied by 12 months plus 175,800 additional homes to account for normal seasonal winter weather. Today we can look back and see that the estimate of 969,000 homes overshot reality by 41,800 new home starts or 4.3%. The chart below shows the seasonally adjusted estimates versus actual starts.

The dashed blue line is when estimates overshoot reality by 180,000 actual starts. When that level has previously been breached, the economy was slowing and a recession was approaching.

Important to this discussion of whether the slowdown in housing is merely weather related, the rise from under- to overestimation of new starts began in December of 2012. This suggests that the economy is already in the early stages of slowing, and the number of "real" housing starts is a reflection of that.

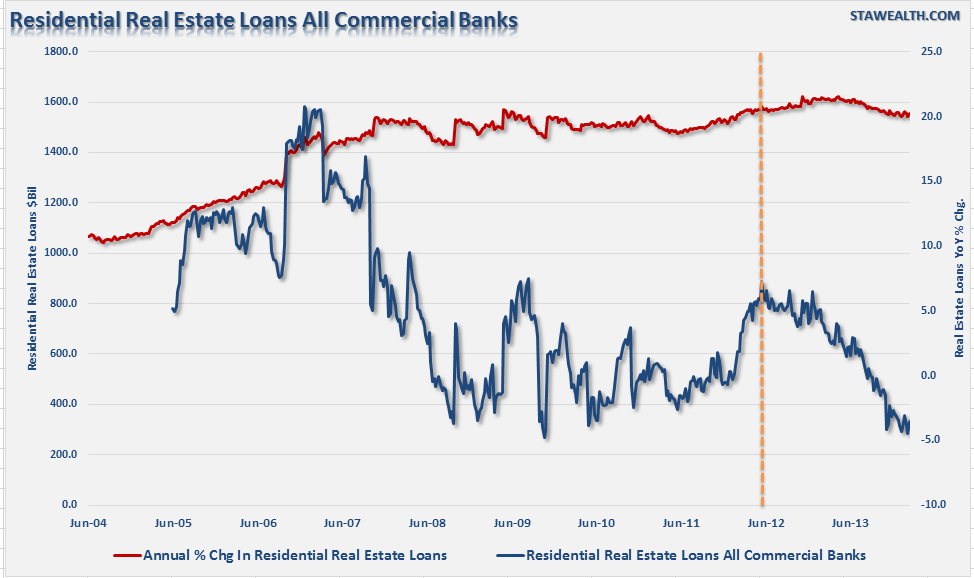

Another indicator that we can look at to determine the whether the weather is entirely to blame for the slowdown in housing is residential loan demand. The chart below shows residential loans by all commercial banks.

The demand for loans also began to slow in 2012, which confirms the slow down in new home starts above.

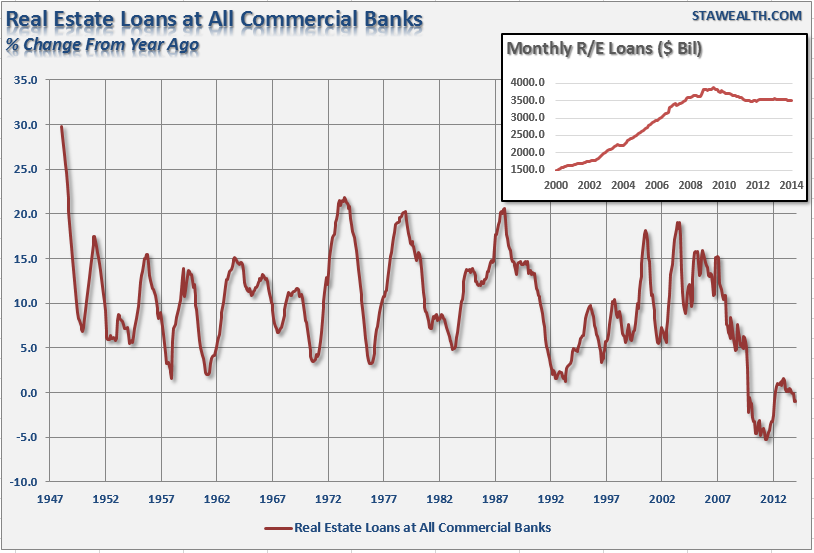

The same is shown in the next chart which is all real estate related loans at all commercial banks. What is also interesting is that loan demand was only able to rise to levels that were previously low points of loan demand going all the way back to 1947. This isn't a sign of a strong and growing economy.

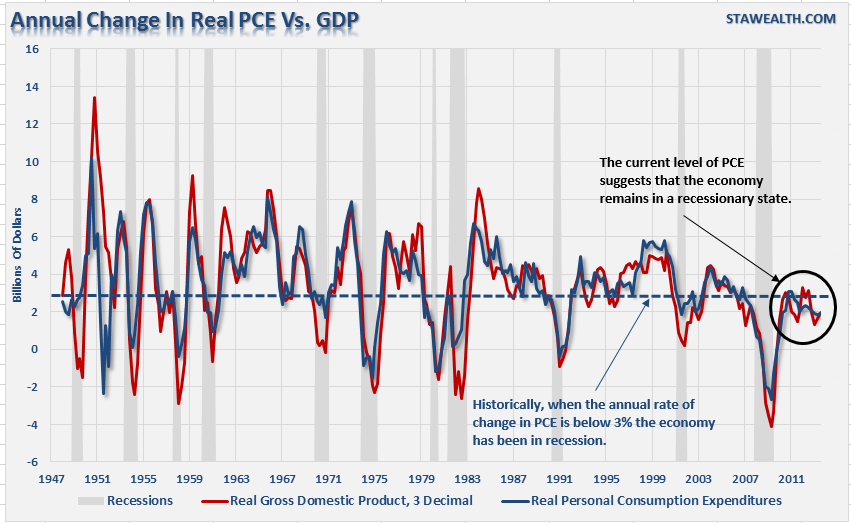

If we step outside of housing, and look at the annualized change in personal consumption expenditures, we see the same evidence of a weakening economic trend. The chart below compares the annual changes of inflation adjusted PCE to GDP. Considering that PCE makes up almost 70% of economic growth today it is not surprising to see such a tight correlation between the two data points.

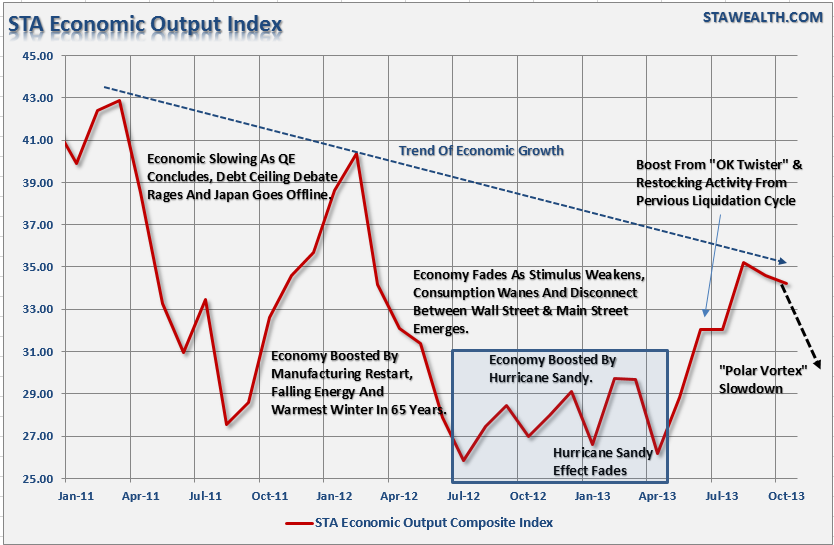

All of the data herein suggests that the current weakness in both housing and the economy is more than just a temporary weather related issue. The good news is that, as discussed previously, the current economic slowdown will likely again lead to an "inventory" restocking cycle.

This has been the case repeatedly seen over the last four years. The problem is that each cycle has been reduced in magnitude as we progress through the current economic "recovery". While the Federal Reserve's artificial interventions continue to pull forward future consumption, the reality is that we are likely much closer to the next recession than not.