Below, Simon White explains what George Osborne’s recent announcement in regard to "spare QE" money really means in regard to government spending and the value of our money. Self-control by government when it comes to budgets in something of great concern to those interested in gold investment, the less restraint shown the greater the chances of an inflationary effect. As the author states, hyperinflation can appear worryingly quickly meaning the decision to invest in gold will not be one that comes back to haunt you.

The UK government recently decided to transfer the coupon income from the Bank of England’s gilt buying program (Asset Purchase Facility (APF)) to the UK Treasury. This is not only an interesting development in itself, but is yet another marker in the slowly evolving relationship between the central banks of the struggling developed market economies and their governments.

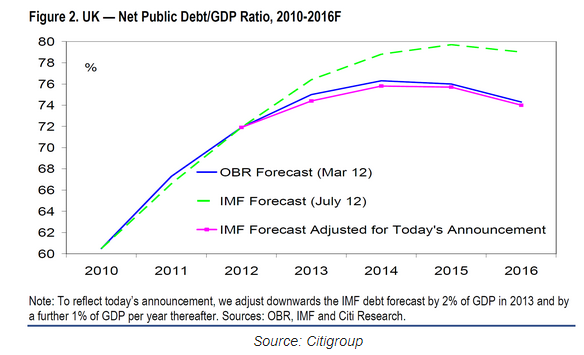

Looking at the UK’s recent action, there are two main effects. First, it will reduce UK’s debt/GDP ratio. The transfer of £35bn initially and roughly £15bn each year after to the UK Treasury will have a material affect on the debt ratio, leaving it about 4% points lower in 2016 (all other things equal) than the IMF’s recent forecast (at 74%).

Secondly, transferring the income has the same effect as buying more gilts as the Treasury has stated it will use the cash to enable it to issue less debt. So, ultimately, the action results in there being less gilts in the market. This is de facto QE, as Mervyn King, the BoE Governor, stated in his letter to the Chancellor acceding to the Treasury’s request.

Except, of course, this was not a request. This is another incremental move towards "fiscal dominance." This is where the fiscal authority ultimately gains the upper hand from the central bank and we see monetisation of public sector deficits and debt. This is the diametric opposite of "monetary dominance," where the central bank forces the government to cut its primary deficit and stabilise the level of public debt outstanding.

It may be eminently sensible for the Treasury, in this case, to receive the interest income, especially as the Bank of England probably would have decided to reinvest the coupon income in more gilts anyway (as the Fed has done with MBS). But what if it had not? This would then have been the Treasury forcing the Bank to ease policy against its will. A clear move towards fiscal dominance.

As Willem Buiter, Citibank’s Chief Economist, has stated, over history, fiscal dominance is the norm. The previous 30 years gave birth to more independent central banks. Governments were happy to allow this as these – as we now know – were the exceptional, NICE (non-inflationary continuous expansion) decades. Governments had little debt so there was no real harm – and indeed perceived benefits – in allowing independent central banks set interest rates to target (principally) inflation.

With the end of the NICE times and many developed governments running large fiscal deficits and alarming debt/GDP ratios, history is stirring, and there is a gradual return to fiscal dominance. In Japan, the line is even less blurred as Ministry of Finance officials have recently attended Bank of Japan policy meetings, and government ministers have spoken openly about wanting easier monetary policy.

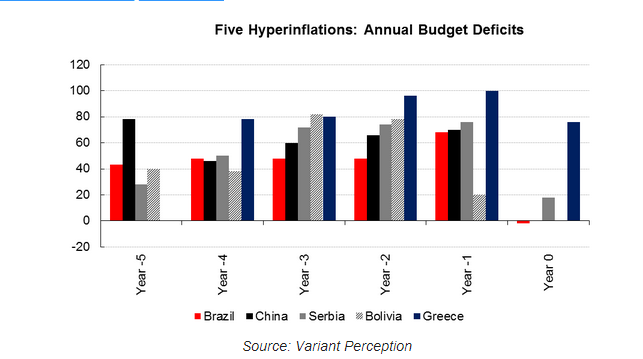

Large and persistent budget deficits, it has been well documented*, are associated with episodes of hyper inflation, as the following chart shows.

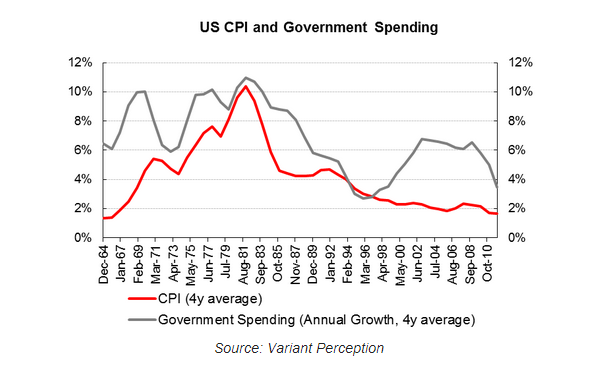

Furthermore, even periods of high, rather than hyper, inflation are associated with high government spending.

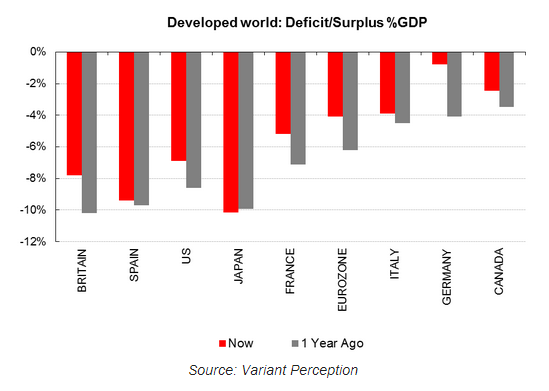

Already, most developed market countries are behind their projections for where they expect their budget balances to be, and almost none have made any serious progress in bringing their deficits down.

The policy of incrementalism towards fiscal dominance in the developed world has profound implications. Governments will show less – not more – restraint with their budgets. The prospect of higher inflation in the years to come is virtually assured, and the aberration of hyperinflation – which has the unsettling knack of taking root alarmingly fast – is no longer dismissible as the prognostications of fantasists.

* Monetary Regimes and Inflation, Peter Bernholz

Please Note: Information published here is provided to aid your thinking and investment decisions, not lead them. You should independently decide the best place for your money, and any investment decision you make is done so at your own risk. Data included here within may already be out of date.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Hinde Capital: The Return To Fiscal Dominance

Published 11/18/2012, 04:22 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

Hinde Capital: The Return To Fiscal Dominance

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.