The net result of these dynamics is official unemployment can soar, but employers will still be scrambling to find qualified, willing employees.

The labor market is viewed as a sea of fluid workers. When one industry shrinks and lays off workers, it's presumed the workers will find employment in an expanding sector. So laid-off construction workers will transition to insurance sales, become waiters, go back to school to train for jobs in the healthcare sector, and so on.

It's also presumed that young workers will automatically be hired and trained in whatever sectors are expanding. The fresh clay of high school/college graduates will be molded into whatever workers employers need.

This isn't how the labor market actually works. People have constraints that limit their willingness and/or ability to transition to new kinds of work. These constraints may be physical--many are unable to do demanding physical work--intellectual--they lack the training or mindset needed for demanding knowledge-work--or emotional: high-stress jobs burn people out.

There are social, cultural, and financial constraints as well. For example, young people will not take jobs in sectors they have no interest in. Trendy fields attract talent, staid fields are avoided. There may be an expectations gap between what young workers expect in pay and workload and what employers are offering.

Although few seem to have noticed, the pandemic lockdown pushed millions of people into discovering ways to survive without taking full-time jobs. People get creative when they have to, and as a result of the lockdown, people found they could get by on much less than they once thought. People found nooks and crannies in the economy outside the conventional mainstream of full-time work in government or Corporate America. They have side hustles, work for cash, rent out rooms, live with Grandma and Grandpa (two Social Security checks, yowza), live in a rent-free micro-house, and so on.

In other words, there is a vast spectrum of mismatches between what employers want and what the workforce is able to do and willing to do for the pay and work being offered. This has forced employers to loosen conventional demands--for example, offering flex-time for working parents, conceding to remote work, etc.--and offers higher pay and upsides (bonuses, stock options, etc.) to retain workers and poach experienced, willing workers from other employers.

As I noted in Here's How We'll Have Labor Shortages and High Unemployment at the Same Time (April 3, 2023), there are also demographic and generational forces in play. Retiring workers are in many cases taking irreplaceable work experience with them, and the replacement workers lack the requisite training and on-the-job problem-solving. Expectations and standards change with each generation.

As I explained in Wages Going Up for Good: Catch-Up and Blowback (May 24, 2023), wages must play catch-up after 45 years of declining purchasing power. A "living wage" in an era of relentlessly higher costs due not just to inflation but to credit-asset bubbles is much higher than it was in previous, lower-cost eras.

Many workers are still earning close to the same hourly rate I made in 1985 ($12/hour) while official inflation has tripled and the cost of housing has risen five or six-fold, along with higher education, childcare, health insurance, etc.

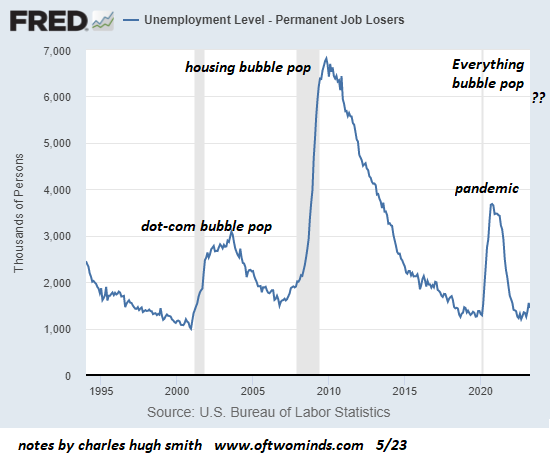

The net result of these dynamics is official unemployment can soar but employers will still be scrambling to find qualified, willing employees. Wages have to rise regardless of unemployment or recession, but few analysts seem to grasp the social and economic forces in play stretch back generations.