With higher electricity prices (and even rising emissions) as a result of the EU’s ‘Green Adventure,’ it is no surprise, then, that the domestic aluminum smelting industry in Europe is at such risk.

Yet for a region so reliant on imported material, Europe still maintains an import tax on primary metal, maybe fearing that its removal would be the final nail in the smelting industry’s coffin.

According to the International Aluminium Institute, Europe’s aluminum production in 2013 was 3.525 million tons, but an EU report published in October of 2013 states that European smelters fall predominantly into two groups: those with captive power generation or long-term power contracts, and those for whom either long-term contracts have expired, or they buy closer to the spot industrial market.

So what are the production costs for each group?

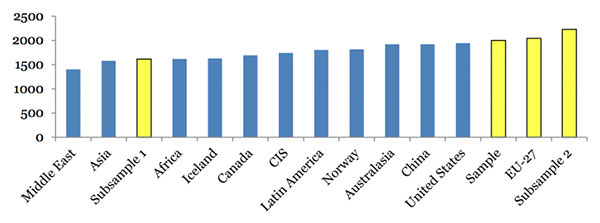

For the latter group, production costs in Europe are the highest in the world, in the region of $2,318 per metric ton when including capital costs and overheads. Even with a physical delivery premium approaching $400 per ton, such smelters are still losing money in today’s market.

For those in the former group, production costs estimated at around $1,992 per metric ton mean they remain competitive with the physical delivery premium.

The question, therefore, is: how much of Europe’s capacity is in the former and how much in the latter?

Of Europe’s approximately 3.5 million tons of capacity, about 2 million tons are estimated by the EU report as being in the higher category and 1.5 million tons in the competitive lower-priced category, supporting Citicorp’s warning that some 2 million tons of capacity is at risk.

The graph above, courtesy of the Citicorp report, of smelter business costs per ton illustrates the comparative positions of sub sample 1 – those smelters on long-term, low-cost power contracts or captive power – and sub sample 2, those buying closer to industrial spot prices.

What This Means for Metal Buyers

It is generally considered unlikely that higher aluminum prices are going to come to the rescue of Europe’s smelters.

Barclays bucks the trend, saying they expect a significant upturn in prices due to a 1.1-million-ton deficit this year and next year, according to Platts. Although they don’t say it outright, that probably pre-supposes the stock and finance model continues. European smelters must be clinging to the hope it does.

by Stuart Burns