At long last, the moment you've been hoping for has arrived: you're pitching your screenplay to a producer. Your agent is cautious but you're confident nobody else has concocted a story as outlandish as yours. Your agent gives you the nod and you're off and running:

Writer: Two guys start a cryptocurrency as a joke to parody the crypto craze, and they name it KittyCoin. It goes nowhere but then the greatest speculative bubble of all time takes off, it's the dot-com and housing bubble times 100 but in everything, and within a couple months the entire economy is dependent on this bubble, and the bubble is dependent on KittyCoin, which has shot up 15,000 percent in a few weeks. A celebrity CEO who's been promoting KittyCoin is invited to host a failing TV variety show, and now the whole economy depends on KittyCoin soaring even higher.

Producer: So it's 'The Big Short' plus 'Network'.

Writer: Something like that, only zanier.

Producer: I get the zaniness but it's so implausible -- it's preposterous.

Writer: It's an absurdist comedy.

Producer: But it ends with everyone being wiped out.

Writer: OK, a tragi-comedy.

And here we are, in the Greatest Bubble of All Time (GBOAT) hanging on the thin thread of speculators rotating out of one bubble into another even more improbable bubble. If there is no heir-apparent for the rotation, then players rotate back into an asset that already reached bubblicious heights and is awaiting the next booster.

The Everything Bubble is one for the ages, but alas, even the most glorious global Tulip Bulb manias crash back to Earth. So how do Everything Bubbles end? Like every other bubble ends:

Preposterous moves to implausible which moves to plausible which moves to inevitable. In other words, bubbles inflating to even more outlandish valuations are no longer merely plausible, they've become inevitable: the Federal Reserve will continue printing money forever, Americans have trillions of dollars in stimmy and savings they're itching to spend, and so on.

All bubbles reach their zenith when plausible becomes inevitable. In the 1920s, it was radio which was clearly the next big thing and indeed it was. But the prospect of decades of growth drove valuations to heights which were disconnected from actual revenues and earnings, and so the bubble burst.

The same thing happened in the dot-com bubble, as the euphoria about decades of future growth lifted valuations to preposterous levels.

Every bubble has a speculative mania component and a credit-leverage component: since gains are inevitable, it would be irrational not to borrow money and leverage greater gambles to maximize the guaranteed gains.

Easy money is an essential fuel in the bubble rocket. With money this easy to borrow and leverage, it's a slam-dunk that the bubble can keep expanding until some far distant time that's so remote we don't have to worry about it, because we'll all sell at the top and be out long before the bubble pops. Uh, right. That's exactly how it works.

Well, not quite. Almost no one gets out at the top, and many of those few who do anxiously re-enter just before the bubble finally pops. This is the pernicious consequence of bubbles becoming inevitable: there is simply no way the Fed will stop printing money, no way Americans won't spend their stimmy, no way inflation won't keep soaring, etc., and so future gains are inevitable.

This certainty pushes valuations to preposterous levels, but they keep on rising, proving the inevitability of continued expansion. This rational exuberance is based on the idea that the rocket will never run out of fuel. Put another way, easy money will always be available to greater fools who will gladly take an asset off our hands at much higher prices.

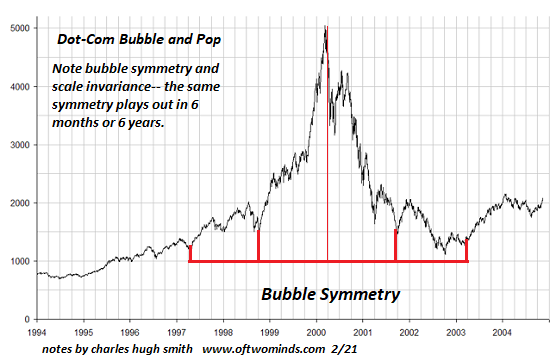

But weirdly, and irrationally, bubbles pop anyway. Bubbles tend to display symmetry, i.e. follow the same trajectory down that they took on the way up, but this isn't a law of nature, it's just a manifestation of psychology: there's typically a last buy the dip pop higher as the multitudes (and their trading bots) have been trained by the inevitability of gains to consider every tiny dip lower as an opportunity to lock in ever greater gains.

The zaniness moves from absurd to tragi-comedy before anyone is aware the third act has begun.