Last week, the Federal Reserve announced it would delay the interest rate liftoff yet again, but while everyone seems concerned about nominal rates—the federal funds rate, in this case—real rates have already risen about 5 percent since August 2011.

This “invisible” rate hike is much more impactful to commodity prices and emerging markets than a nominal rate hike, which is simply the “tip of the iceberg.”

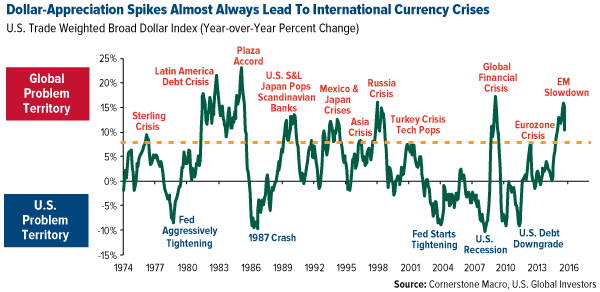

Since July 2014, the U.S. dollar has appreciated more than 20 percent. This has had huge implications for net commodity exporter countries, both developing and emerging, which typically see their currency rates fluctuate when prices turn volatile.

But why does this happen?

The main reason is that most commodities, including crude oil, metals and grains, are priced in U.S. dollars. They therefore share an inverse relationship. When the dollar weakens, prices tend to rise. And when it strengthens, prices fall, among other past ramifications, as you can see in the chart below courtesy of investment research firm Cornerstone Macro.

Indeed, commodities have collectively depreciated close to 40 percent since this time a year ago and are at their lowest point since March 2009. We might very well have reached an inflection point for commodities, which opens up investment opportunities.

Net Commodity Exporters Under Pressure

The number of developing and emerging markets that are dependent on commodity exports has risen in recent years, from 88 five years ago to 94 today, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Many of these countries—located mostly in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia—have a dangerously high dependency on a small number of not only commodity exports but also trading partners.

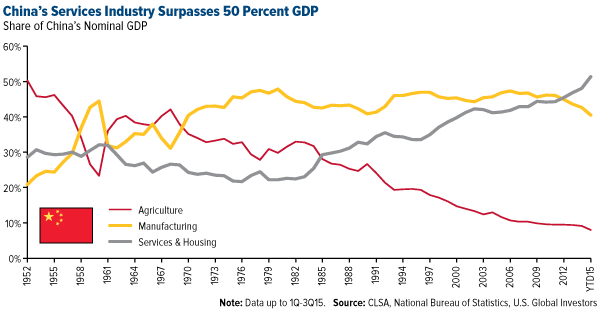

For many suppliers, China is the leading buyer. But the Asian giant’s imports have been slowing as its economy transitions from manufacturing to services and housing, forcing many net commodity export countries to rethink their dependency on China.

This is the position Indonesia finds itself in right now. As much as 50 percent of its total exports consists of crude oil, palm oil, copper, coal and rubber, of which China has historically been a vital importer. A stunning 95 percent of Mongolia’s exports flow into its southern neighbor, according to the World Factbook. For Chile, commodities represent close to 90 percent of total exports, about 25 percent of which goes to China.

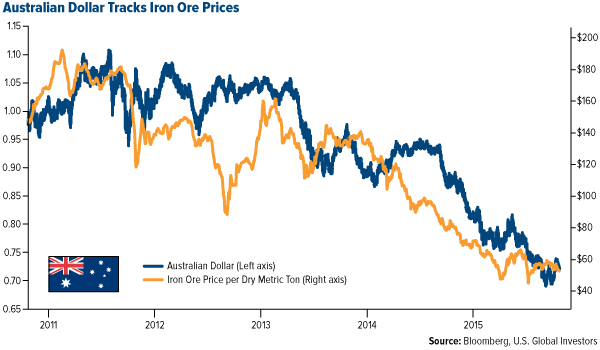

But countries needn’t have such a high dependency on commodities for their currencies to be affected. The Australian dollar, for instance, has a positive correlation with iron ore prices.

About 98 percent of the world’s iron ore supply is used to make steel. So important is the metal to the state of Western Australia, where most of the continent’s deposits can be found, that every $1 decline in prices results in an estimated $49 million budget loss.

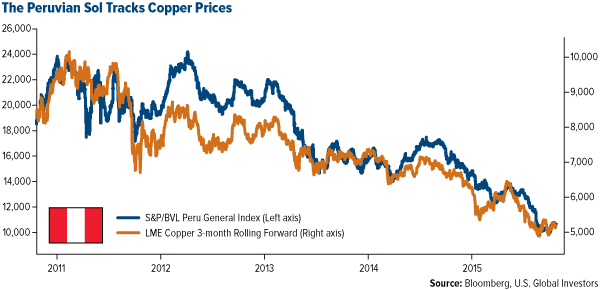

The same relationship exists between the Peruvian sol and copper. Peru is the fourth-largest copper producer in the world, preceded by Chile, China and the U.S.

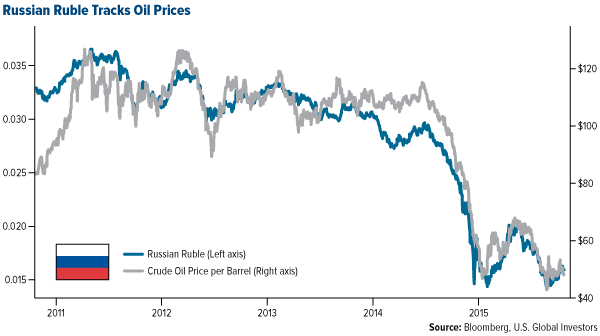

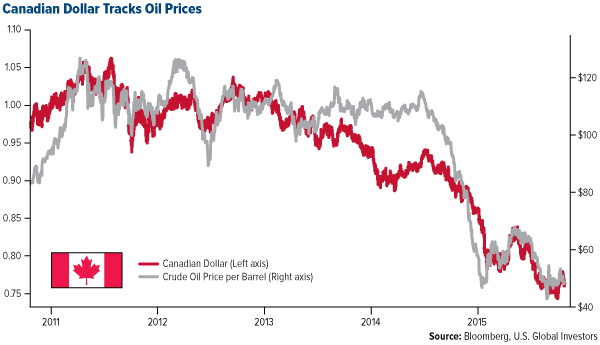

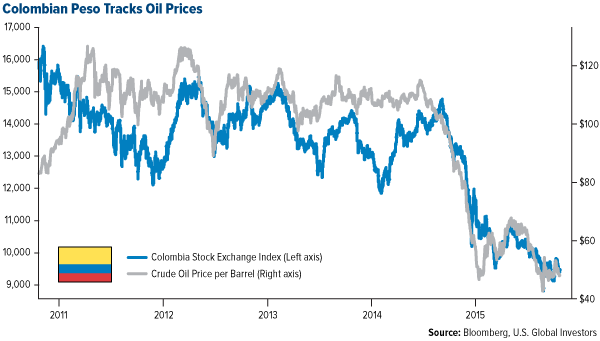

The Russian ruble, Canadian dollar and Colombian peso all follow crude oil prices. (Russia is the third-largest oil producer in the world; Canada, the fifth-largest; Colombia, the 19th-largest.)

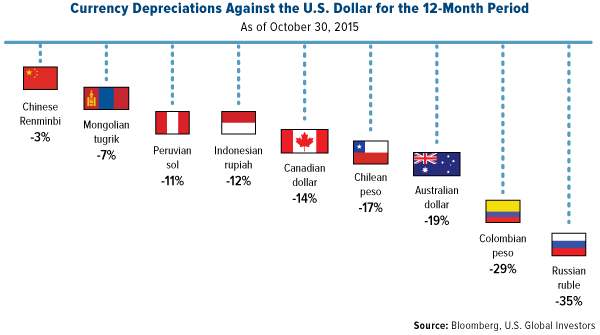

It’s important that we see stability in emerging market currencies, which would help support resources demand. We’ve seen some stabilization in the Chinese renminbi after it was depreciated in August, but a few others are down pretty significantly.

Global Manufacturing Could Reverse Course Sooner Than You Think

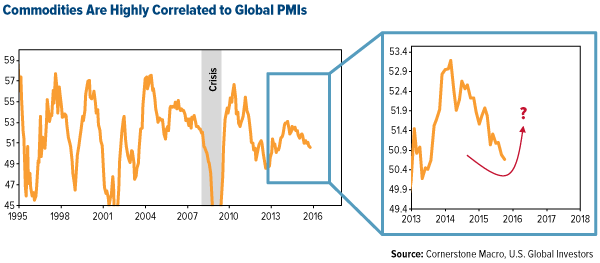

I’ve shown a number of times that commodity demand depends on manufacturing strength, as measured by the J.P. Morgan Global Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI). This indicator has steadily been trending lower. Although the reading is still above the neutral 50.0 line, commodity prices have reacted negatively.

Cornerstone Macro believes both the Chinese and global PMI are “likely” to rise in October, leading to a full year of upside potential. If true, this is indeed welcome news, but it’s worth remembering that the PMI looks ahead six months, meaning it’ll take approximately that long for commodities to recover.

In any case, now might be a good time for investors to consider getting back into commodities and natural resources since we could be in the early innings of an upturn. “You want to buy commodity stocks when they’re out of favor, because they are cyclical,” Brian Hicks, portfolio manager of our Global Resources Fund, told The Energy Report last week. “If you look out 12, 18, 24 months from now, those equity values should reflect equilibrium commodity prices and move significantly higher from here.”

Disclosure: The J.P. Morgan Global Purchasing Manager’s Index is an indicator of the economic health of the global manufacturing sector. The PMI index is based on five major indicators: new orders, inventory levels, production, supplier deliveries and the employment environment.

All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the link(s) above, you will be directed to a third-party website(s). U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by this/these website(s) and is not responsible for its/their content.