“Wow!”

That is all I could utter as my brain spun listening to an interview with Chamrath Palihapitiya on CNBC last week.

“I don’t see a world in which we have any form of meaningful contraction nor any form of meaningful expansion. We have completely taken away the toolkit of how normal economies should work when we started with QE. I mean, the odds that there’s a recession anymore in any Western country of the world is almost next to impossible now, save a complete financial externality that we can’t forecast.”

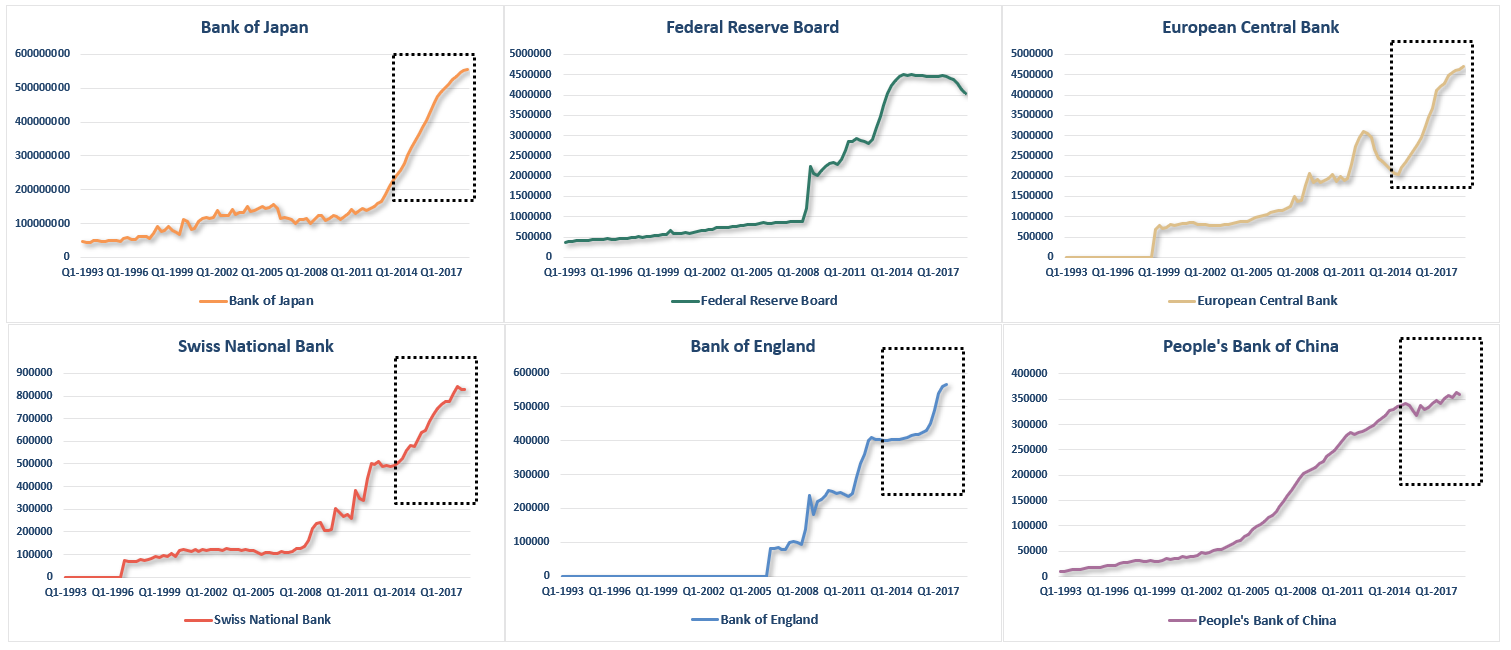

It is a fascinating comment particularly at a time where the Federal Reserve has tried, unsuccessfully, to normalize monetary policy by raising interest rates and reducing their balance sheet. However, an almost immediate upheaval in the economy, not to mention reprisal from the Trump Administration, brought those efforts to a halt just a scant few months after they began.

A quick Google search on Chamrath revealed a pretty gruesome story about his tenure as CEO of Social Capital which will likely cease existence soon. However, his commentary was interesting because, despite an apparent lack of understanding of how economics works, his thesis is simply that economic cycles are no longer relevant.

This is the quintessential uttering of “this time is different.”

Economists wanting to get rid of recessions is not a new thing.

Emi Nakamura, this year's winners of the John Bates Clark Medal honoring economists under 40, stated in an interview that she:

“…wants to tackle some of her fields’ biggest questions such as the causes of recessions and what policy makers can do to avoid them.”

The problem with Central Bankers, economists, and politicians intervening to eliminate recessions is that while they may successfully extend the normal business cycle for a while, they are most adept at creating a “boom to bust” cycles.

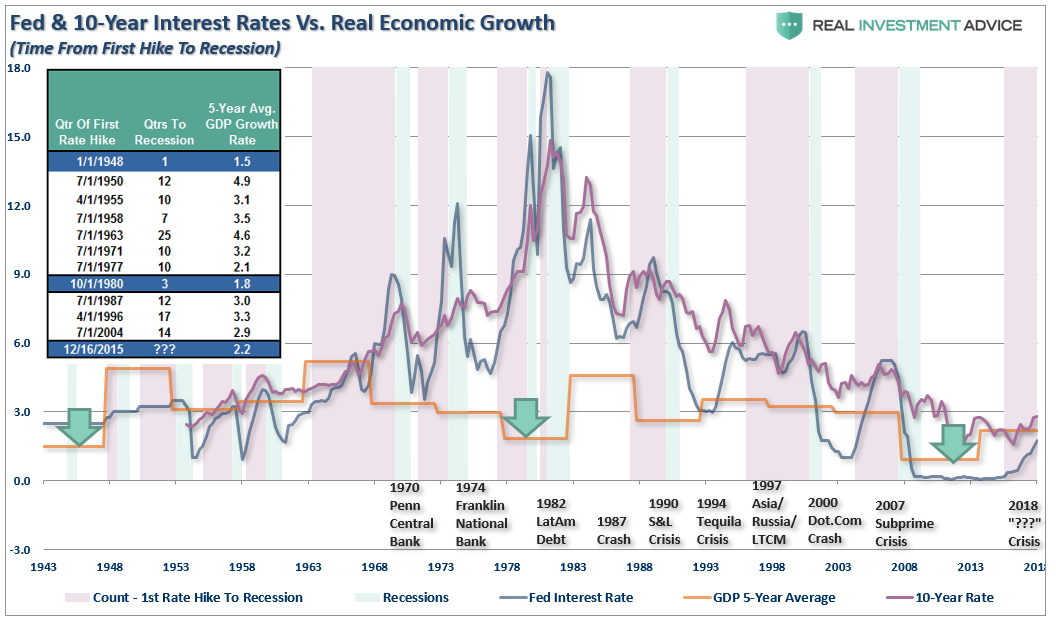

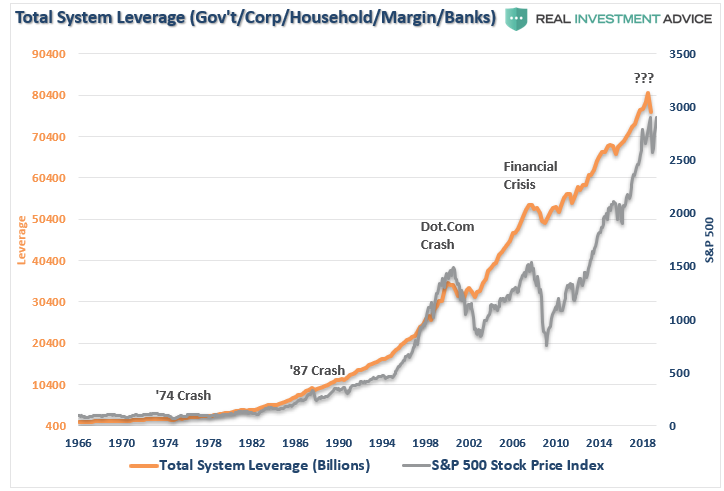

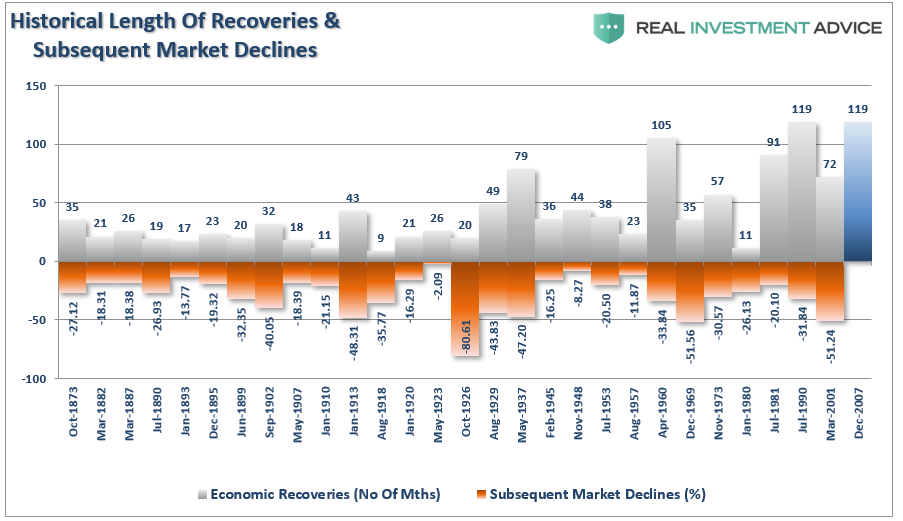

To be sure the last three business cycles (80s, 90s and 2000) were extremely long and supported by a massive shift in financial engineering and credit leveraging cycle. The post-Depression recovery and WWII drove the long economic expansion in the 40’s, and the “space race” supported the 60’s. You can see the length of the economic recoveries in the chart below. I have also shown you the subsequent percentage market decline when they ended.

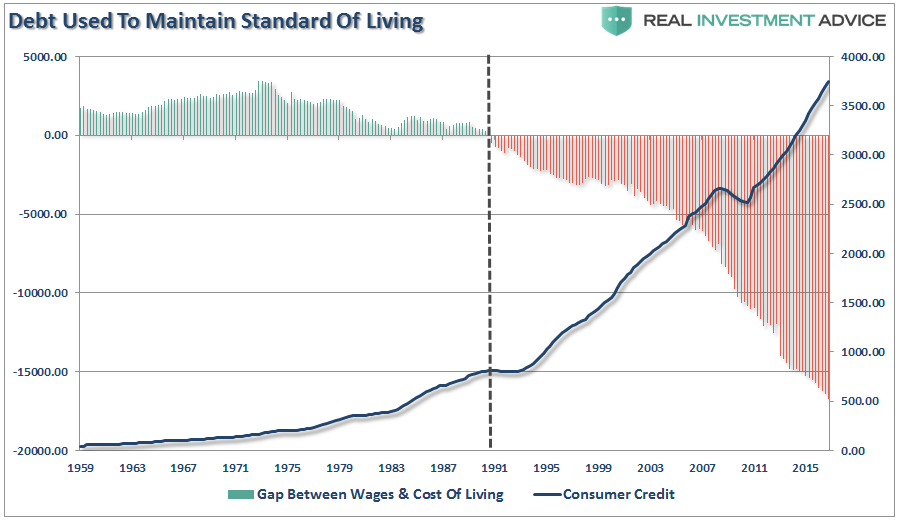

Currently, employment and wage growth is fragile, 1-in-4 Americans are on Government subsidies, and the majority of American’s living paycheck-to-paycheck. This is why Central Banks, globally, are aggressively monetizing debt in order to keep growth from stalling out.

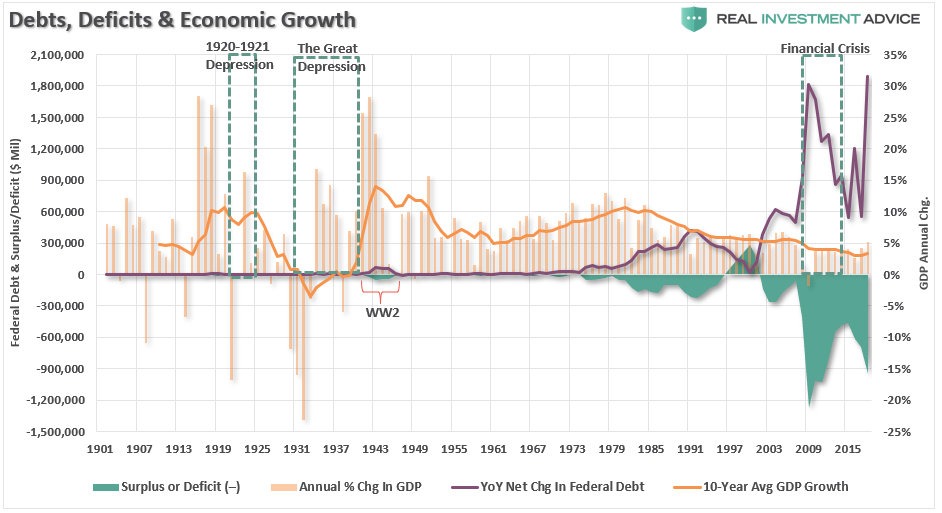

Despite a surging stock market and an economy tied for the longest economic expansion in history, it is also is running at the weakest rate of growth with the highest debt levels…since “The Great Depression.”

Recessions Are An Important Part Of The Cycle

I know, I get it.

If you mention the “R” word, you are a pariah from the mainstream proletariat.

This is because people assume if you talk about a “recession” you mean the end of the world is coming.

The reality is that recessions are just a necessary part of the economic cycle and arguably a crucial one. Recessions remove the “excesses” built up during the expansion and “reset” the table for the next leg of economic growth.

Without “recessions,” the build-up of excess continues until something breaks. The outcomes of previous attempts to manipulate the cycles have all had devastating consequences.

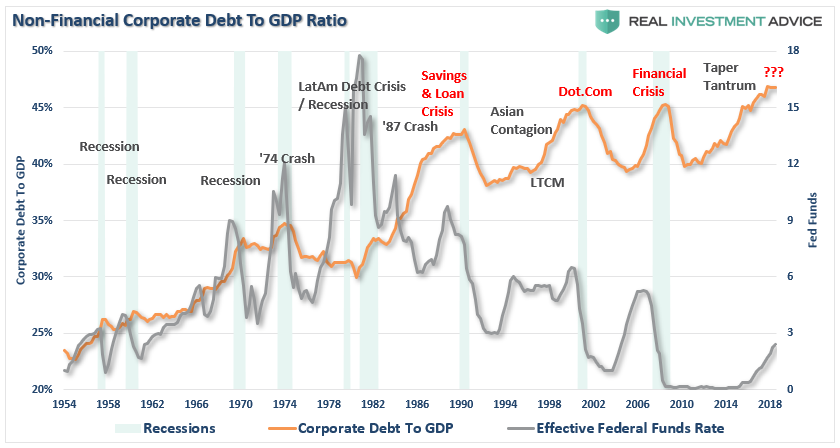

In the current cycle, the Fed’s interventions and maintenance of low rates for a decade have allowed fundamentally weak companies to stay in business by taking on cheap debt for unproductive purposes like stock buybacks and dividends. Consumers have used low rates to expand their consumption through debt once again. The Government has piled on debts and increased the deficit to levels normally seen during a recession. Such will only serve to compound the problem of the next recession when it comes.

However, it is the Fed’s mentality of constant growth, with no tolerance for a recession, has allowed this situation to inflate rather than allowing the natural order of the economy to perform its Darwinian function of “weeding out the weak.”

The two charts below show both corporate debt as a percentage of economic growth and total system leverage versus the market.

Do you see the issue?

The fact that over the past few decades the system has not been allowed to reset has led to a resultant increase in debt to the point it has impaired the economy to grow. It is more than just a coincidence that the Fed’s “not-so-invisible hand” has left fingerprints on previous financial unravellings.

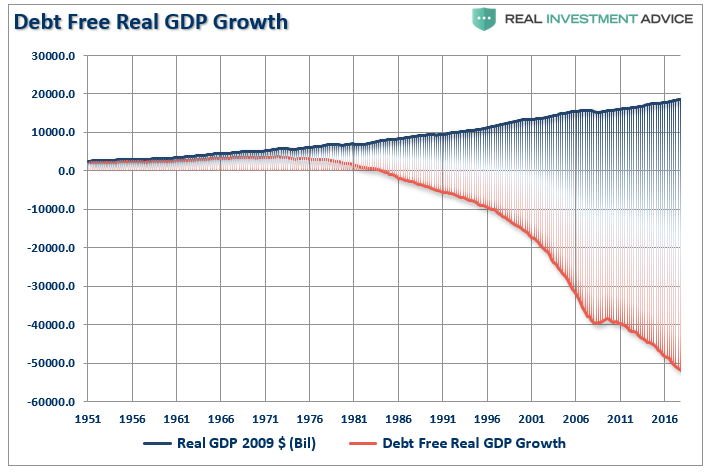

Given the years of “ultra-accommodative” policies following the financial crisis, the majority of the ability to “pull-forward” consumption appears to have run its course. This is an issue that can’t, and won’t be, fixed by simply issuing more debt which, for the last 40 years, has been the preferred remedy of each Administration. In reality, most of the aggregate growth in the economy has been financed by deficit spending, credit creation, and a reduction in savings.

In turn, this surge in debt reduced both productive investments into, and the output from, the economy. As the economy slowed, and wages fell, the consumer was forced to take on more leverage which continued to decrease the savings rate. As a result, of the increased leverage, more of their income was needed to service the debt.

Since most of the government spending programs redistribute income from workers to the unemployed, this, Keynesians argue, increases the welfare of many hurt by the recession. What their models ignore, however, is the reduced productivity that follows a shift of resources from productive investment to redistribution.

All of these issues have weighed on the overall prosperity of the economy and what has obviously gone clearly awry is the inability for the current economists, who maintain our monetary and fiscal policies, to realize what downturns encompass.

The Keynesian view that “more money in people’s pockets” will drive up consumer spending, with a boost to GDP being the result, is clearly wrong. It has not happened in four decades. What is missed is that things like temporary tax cuts, or one time injections, do not create economic growth but merely reschedules it. The average American may fall for a near-term increase in their take-home pay and any increased consumption in the present will be matched by a decrease later on when the tax cut is revoked.

This is, of course, assuming the balance sheet at home is not broken. As we saw during the period of the “Great Depression” most economists thought that the simple solution was just more stimulus. Work programs, lower interest rates, government spending, etc. did nothing to stem the tide of the depression era.

The problem currently is that the Fed’s actions halted the “balance sheet” deleveraging process keeping consumers indebted and forcing more income to pay off the debt which detracts from their ability to consume. This is the one facet that Keynesian economics does not factor in. More importantly, it also impacts the production side of the equation since no act of saving ever detracts from demand. Consumption delayed, is merely a shift of consumptive ability to other individuals, and even better, money saved is often capital supplied to entrepreneurs and businesses that will use it to expand, and hire new workers.

The continued misuse of capital and continued erroneous monetary policies have instigated not only the recent downturn but actually 40-years of an insidious slow moving infection that has destroyed the American legacy.

Here is the most important point.

“Recessions” should be embraced and utilized to clear the “excesses” that accrue in the economic system during the first half of the economic growth cycle.

Trying to delay the inevitable, only makes the inevitable that much worse in the end.

The “R” Word

Despite hopes to the contrary, the U.S., and the globe will experience another recession. The only question is timing.

As I quoted in much more detail in this past weekend’s newsletter, Doug Kass suggests there is plenty of “gasoline” awaiting a spark.

- Slowing Domestic Economic Growth

- Slowing Non-U.S. Economic Growth

- The Earnings Recession

- The Last Two Times the Fed Ended Its Rate Hike Cycle, a Recession and Bear Market Followed

- The Strengthening U.S. Dollar

- Message of the Bond Market

- Untenable Debt Levels

- Credit Is Already Weakening

- The Abundance of Uncertainties

- Political Uncertainties and Policy Concerns

- Valuation

- Positioning Is to the Bullish Extreme

- Rising Bullish Sentiment (and The Bull Market in Complacency)

- Non-Conformation of Transports

But herein lies the most important point about recessions, market reversions, and systemic problems.

What Chamrath Palihapitiya said was both correct and naive.

He is naive to believe the Fed has “everything” under control and recessions are a relic of the past. Central Banks globally have engaged in a monetary experiment hereto never before seen in history. Therefore, the outcome of such an experiment is also indeterminable.

Secondly, when Central Banks launched their emergency measures, the global economies were emerging from a financial crisis not at the end of a decade long growth cycle. The efficacy of their programs going forward is highly questionable.

But what Chamrath does have right were his final words, even though he dismisses the probability of occurrence.

“…save a complete financial externality that we can’t forecast.”

Every financial crisis, market upheaval, major correction, recession, etc. all came from one thing – an exogenous event that was not forecast or expected.

This is why bear markets are always vicious, brutal, devastating, and fast. It is the exogenous event, usually credit related, which sucks the liquidity out of the market causing prices to plunge. As prices fall, investors begin to panic sell driving prices lower which forces more selling in the market until, ultimately, sellers are exhausted.

It is the same every time.

While investors insist the markets are currently NOT in a bubble, it would be wise to remember the same belief was held in 1999 and 2007. Throughout history, financial bubbles have only been recognized in hindsight when their existence becomes “apparently obvious” to everyone. Of course, by that point is was far too late to be of any use to investors and the subsequent destruction of invested capital.

This time will not be different. Only the catalyst, magnitude, and duration will be.

My advice to Emi Nakamura would be instead of studying how economists can avoid recessions, focus on the implications, costs, and outcomes of previous attempts and why “recessions” are actually a “healthy thing.”