The chances of a disorderly Greek exit from the euro have risen materially in the past couple of weeks, in our view. And after the weekend's "No" vote, we now think the chances of that happening are slightly more than 50%. So it is still a close call.

At this stage, we'd emphasise the uncertainty, rather than absolute probabilities. That may not be ideal, but it is realistic. There is still a chance of a deal between Greece and its creditors. And, even in the event of failure, a Greek exit from the euro would not be definite, even if might be the likely outcome.

In this note we lay out the various turnings from which Greece, its creditors, or the ECB could swerve away from the more negative outturns, as well as examine the short- and medium-term risks of economic and financial contagion. Given the erosion of trust between the creditors and Greece, if there were to be a last minute deal, it would need to be crafted extremely sensitively. And even then, it is by no means clear it would be acceptable to the governments – and some parliaments – of euro area member states. But there is still a chance.

The lifeline that is keeping Greece in the single currency (or indeed, the single currency in Greece) is the ECB's provision of Emergency Liquidity Assistance to the Greek banks. While it remains capped, the banks will need to remain closed. But while it remains in place, they'll at least remain going concerns. Although yesterday's increase of collateral haircuts should have no material impact, we'd read it as a strong signal that the ECB would have no compunction withdrawing support of Greek defaults to the ECB on 20 July.

As we discussed last week, if ELA were to be withdrawn, the consequences for the Greek banking system would be grave, and of the options available to the Greek government at that point, a switch to a new currency – though challenging – would be the most likely outcome.

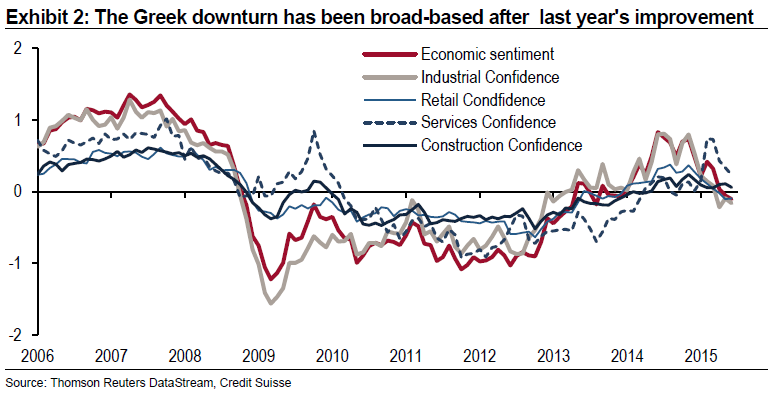

Finally, we revisit the possible channels of contagion. In the near term, the main vulnerability could be business confidence. Uncertainty has risen materially, sufficient to dampen corporate animal spirits. So there are material downside risks to our growth forecasts.

Financial contagion has, so far, been limited. But it may just be dormant. In particular, we'd worry that the correlation between the election of a radical government and the collapse of its banking system means markets will be acutely sensitive to rising support for radical parties – left and right – elsewhere in the euro area.

A new hope after the referendum. Can a deal be made?

Time is short, with political and implementation hurdles still high, but a deal could be reached nonetheless. We lay down below the conditions and tentative timetable for a possible positive outcome in the negotiations.

Pre-condition for a deal. For a compromise to be reached, the first – necessary, but not sufficient – condition was to bring to the negotiation table a proposal of the Greek government that could be seen as credible and acceptable by the Eurogroup, firstly – as the latter needs to validate the request for any ESM support – and then by the institutions, which need to check the technical viability of the proposal.

United Parties of Greece. This proposal has apparently only been delivered orally to euro area partners today in Brussels, which is not ideal – with the promise to provide a more formal document tomorrow. The fact that Greek PM Tsipras got the backing for negotiations from the main pro-European Greek opposition leaders reinforces at the margin its political appeal for the creditors, in our view, as well as insuring the parliamentary approval of a final agreement, if and when it is concluded. Indeed, it suggests to us that the country as a whole is behind the negotiations, in a move towards national responsibility that is a first since the start of the crisis.

Restart negotiations from where they left off before the referendum… Although at the time of writing we don’t have the details of the Greek proposal, the contours should be close to the draft sent by Tsipras to the Institutions on 1 July – at least in spirit, given that the economy has deteriorated over the past few weeks and a new economic scenario has to be taken into account to make sensible fiscal projections.

That draft proposal largely mimicked the one presented a couple of days before by the Institutions – with identical targets for primary surpluses over 2015-2018, matching VAT rates and important concessions from the Greek government on pensions – with only minor remaining differences (see Exhibit 4 below).

In addition, PM Tsipras is asking for some more explicit debt relief, albeit in a 'soft' form. Indeed, the Greek parties' joint statement asks for:

“a commitment to the start of an essential discussion as regards tackling the problem of the sustainability of Greek public debt”.

The debt question. Debt relief, in that 'soft version', could be discussed in the Eurogroup, in our view. Some form of conditional relief should be acceptable for creditors, as it was more or less explicitly promised in November 2012 by the Eurogroup itself. The key conditions for debt relief to be included in negotiations are: (1) the absence of outright (nominal) debt cut requests, and (2) that any maturity extension or lower interest payments are conditional on the implementation of the programme.

We would also argue that debt relief is not, in our view, a key relevant financial issue – see the box below – although it is clearly a strong political one for Greece, that could constitute a deal breaker if formulated sensitively.

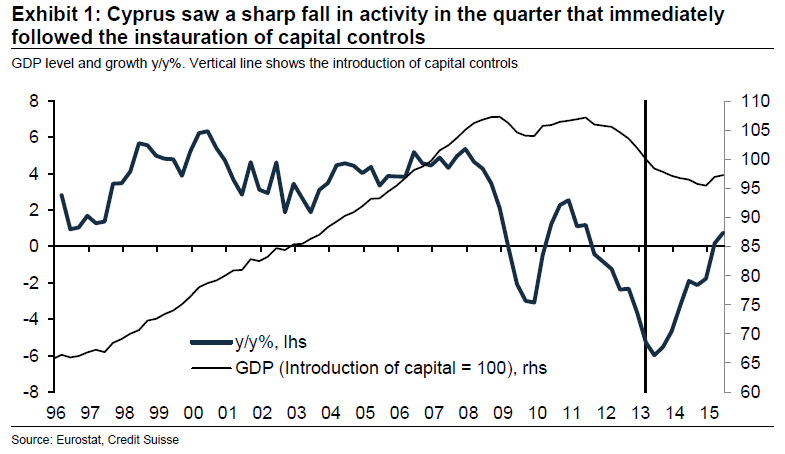

Closed banks and a deteriorated economic backdrop will require new funds. More relevant than the debt question is the fact that the economy is now in recession and that banks are closed. Cyprus saw a sharp fall in activity in the quarter that immediately followed the instauration of capital controls, although it can be showed that it was also the trough in momentum for that economy (Exhibit 1).

For Greece, it means that additional resources would likely be needed to recapitalise the banks and to deal with the cyclical deterioration and its impact on fiscal dynamics. That means additional austerity, or more money from the creditors, which some members might be reluctant to provide, especially in the absence of a very strong commitment from the current government to enact the program's action points in full.

Both sides need to move to reach a positive outcome. Overall, if Greece is willing to start afresh and be both more conciliatory and committed, helped by the backing of a very large majority in the Parliament, and if the creditors are willing on that basis to consider providing additional support, then we believe a deal remains possible in the coming days.

Timetable for a potential deal – The Eurogroup must first agree to restart negotiations with Greece. That requires a formal request for entering a programme from Greece, and unanimity of the finance ministers – they must all be convinced that Tsipras' proposal is serious and that he wants to credibly engage in a negotiation process. If that's the case, and given that a formal request was still not provided today by the Greek government, tomorrow is the earliest possible date for such a first step, although it might instead come after further negotiations (and other extraordinary Eurogroup meetings) in the coming days.

Once this is done, the institutions will need to work on the technical aspects of an agreement, in order for it to be compatible with the targets in the context of a revised (deteriorated) economic and financial outlook.

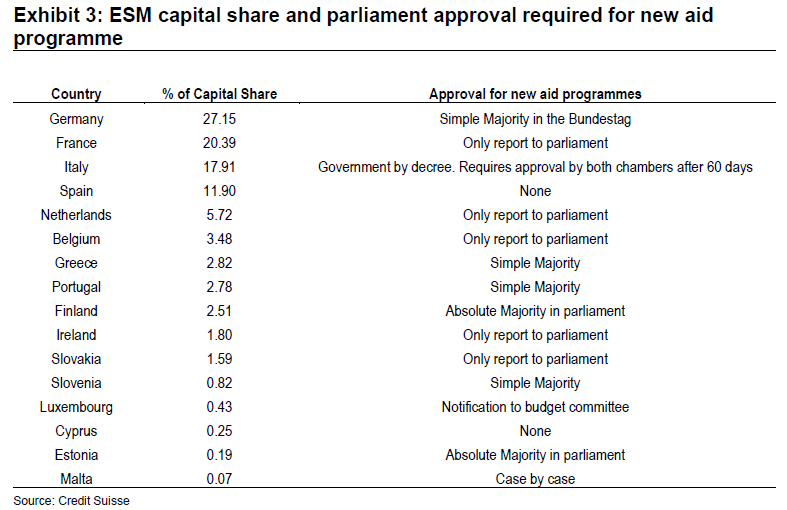

A final version of the proposal, with the approval from the Institutions, should pave the way for an ESM programme that would then be approved by the Greek parliament, with swift implementation of the so-called "prior actions", followed by the approval from the ESM (and from the relevant national parliaments as well, see Exhibit 3) of the agreement. The ESM would then be in the position to release funds in the following days (technically, it would be possible to disburse funds in only a few hours after a positive decision to proceed with a programme) – hopefully in time for the repayment of the ECB-held GGBs, maturing on 20 July. That date might be a stretch, but possible if all proceeds according to the optimistic plan we have discussed above.

Even under this positive scenario, however, banks will remain under capital controls for several months, we believe, with probably only a progressive relaxation of the restrictions, as in the case of Cyprus in 2013.

To Read the Entire Report Please Click on the pdf File Below