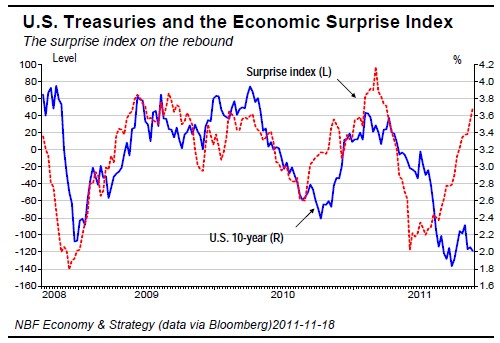

Last month we noted that economic indicators had become more encouraging, a development that did much to dissipate market apprehensions of a second U.S. dip into recession. Indicators since then have generally continued to surprise on the upside. Retail sales and industrial production were both up strongly in October. In mid-November the four-week moving average of U.S. initial jobless claims fell below 400,000 for the first time in seven months. The fourth quarter has started on an upbeat note.

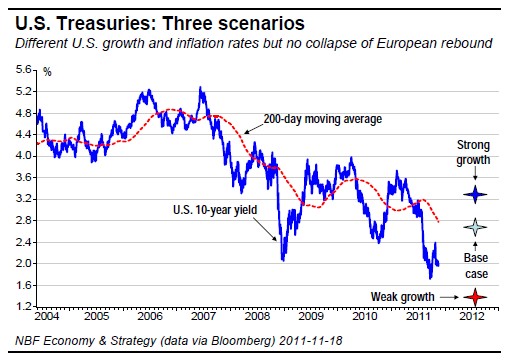

Treasury yields would normally have been expected to react to the run of good news more vigorously than they did. Though declines in commodity prices suggest that 12-month inflation will decelerate further in 2012, 10-year Treasuries are in our view trading at a lower yield than purely domestic economic factors would suggest.

The FOMC‘s program of selling short-term securities to extend the average maturity of its balance sheet is obviously a factor (a contribution of 20 to 30 basis points) in keeping the 10-year yield close to 2%. So are comments by some Fed officials expressing unhappiness with the high unemployment rate and an inclination to support further Fed initiatives as long as expected benefits are greater than costs.

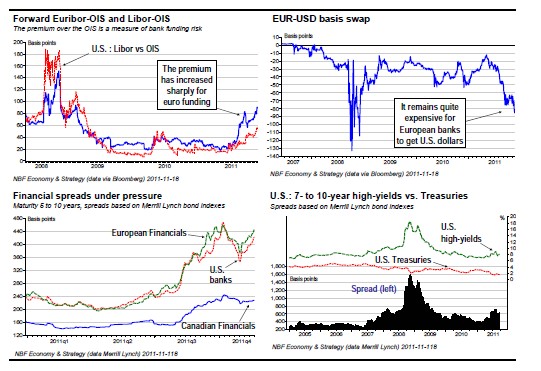

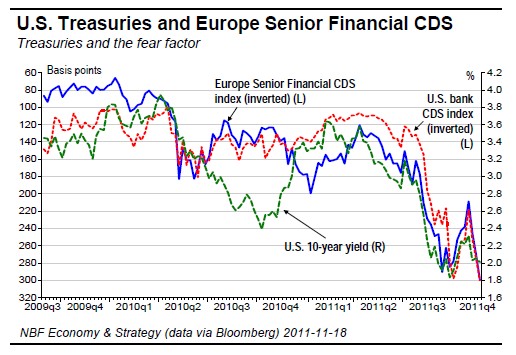

That said, the European sovereign-debt crisis remains a major source of economic and financial risk to the world economy. Many indicators are flashing the persistent concern of credit-markets about Europe and the risk of contagion it presents to international financial markets.

On this subject, Fitch Ratings noted recently that while “U.S. banks have hedged part of their European exposure through the credit default swap market, this tactic could prove problematic if ‘voluntary’ debt forgiveness becomes more prevalent and [sovereigndebt] CDS contracts are not triggered.” In other words, the balance sheets and credit ratings of U.S. banks could be affected. It is not just investors who are worried about the threat to liquidity and financial intermediation presented by the sovereign-debt crisis central bankers also appear ill at ease. As Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney noted in a recent speech: “Global liquidity has fluctuated wildly over the past five years, and we are on the cusp of another retrenchment. There are steps that can be taken to mitigate, but not eliminate, the negative effects of the current wave. How European banks choose to delever will determine which ones authorities around the world need to take.”

This is obviously an environment more favourable to safe and liquid assets like Treasuries than to risky ones. Thus it is not surprising to see 10-year Treasuries correlating more closely with measures of risk, such as credit default swaps on financial institutions, than with some recent economic data.

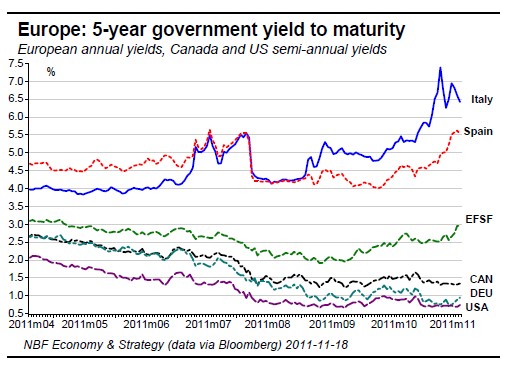

The state of the European economy, whose weakening growth going into 2012 is likely to raise more questions about the health of Italian and Spanish public finances, is a key consideration in forecasts of U.S. interest rates in the coming months.

Investor confidence in the ability of European authorities to put an effective firewall in place appears somewhat shaky. The yield spread between 5-year bonds issued by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and those issued by Germany has widened from 45 basis points to 200.

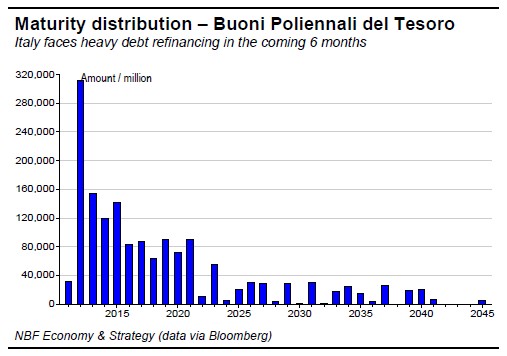

Political pressure on the European Central Bank to intervene more aggressively is mounting. Over the next five months Italy must refinance more than €200 billion of its debt. The ECB certainly has the resources to move more aggressively to support the functioning of the bond market. Yet the truth of the matter is that credible long-term fiscal plans and structural reforms are a prerequisite to resolution of the crisis. Without them the ECB balance sheet will only be flooded over time with bad debt. This is not a long-term solution.

In the meantime, tensions are building. Even Mario Draghi, the incoming ECB president, has questioned the will of politicians to act, citing the failure of governments to make the EFSF a more potent tool for erection of a firewall in the 18 months since it was launched.

Can Italy’s new prime minister, Mario Monti, and his government of technocrats put the country on the road to needed reforms? This remains to be seen. History offers some hope. Back in the 1990s, Italy had two technocratic governments. The second, lasting 15 months, was led by Lamberto Dini, who until then had been treasury minister. Mr. Dini, a former central banker, appointed a cabinet consisting entirely of nonparliamentarians – judges, professors, a general, the manager of a former state company. His government did pass pension reforms.

In the current environment, the action or inaction of politicians is a major factor in the outlook for the bond market. If they succeed in containing the European threat, 10-year Treasuries are likely to be trading around 2.65% latter next summer. If they don’t, we would expect a sustained move below 2%, to 1.4% or lower.

… and in Canada

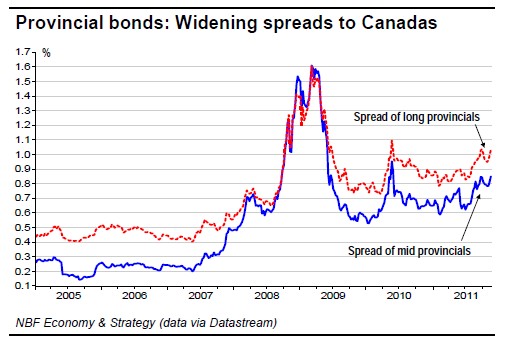

With developments in Europe fuelling investor concern about global growth and market liquidity (Italian 10- year bonds traded briefly above 7.4% in the second week of November), the spreads of broad provincial indexes to Canadas have been volatile.

The volatility of the provincial bond market can also be seen in a specific bond. The current Ontario 10-year, which in mid August was yielding 81 basis points (bps) above the comparable Canada, traded as wide as 96 bps in late September. The spread narrowed to 84 bps in October, then widened again to 93 bps at the close on November 18.

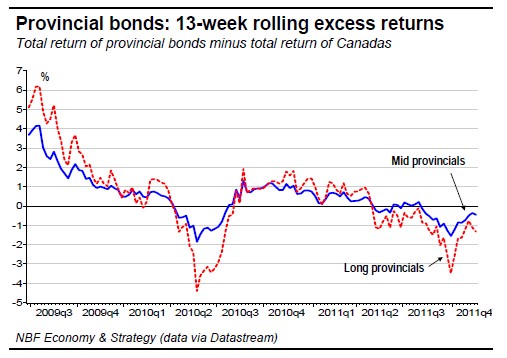

Looking at the broad indexes, long provincials have generated a total return of 2.35% over the last 13 weeks, underperforming comparable Canadas by 132 bps. Provincials maturing in 5 to 10 years returned 1.0%, 45 basis points less than Canadas. In the shorter leg of the spectrum (1 to 5 years), provincials outperformed by 10 bps, generating a total return of 0.41%.

Although we still forecast economic growth in 2012 and in less volatile times we would be happy holding provincials 10 bps tighter to Canada than their current levels, the perception is that investors could react negatively if economic headwinds were to derail provincial plans to balance budgets and stabilize debtto- GDP ratios within a reasonable time. Thus we remain cautious. That said, a further widening of roughly 10 basis points, bringing back the spreads of April 2010, would entice us to build up portfolio exposure to 10-year provincials. In the mean time, provincial bonds with maturity in 2017 and 2018 depending on the issuer are providing an attractive opportunity to benefit from rolling down the yield curve over time. For the time being low rates for longer seems to be likely.

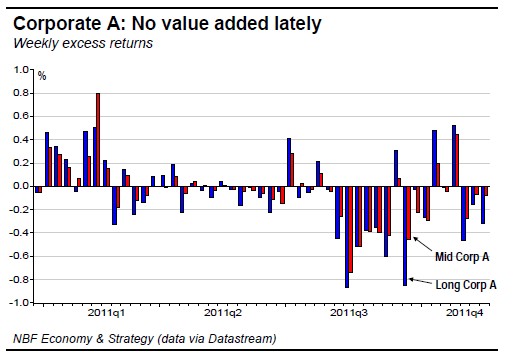

Weekly excess returns for mid and long A-rated corporates since early Q2 show them underperforming Canadas pretty consistently. Still, they have returned 8.3% and 13.28% respectively over the year to date – way ahead of the stock market (−9.6%). But Canadas have done much better – 10.16% for mid terms and 15.85% for maturities longer than 10 years.

Given the significant downside risks to our economic scenario from strains in global financial markets, we are maintaining a neutral duration while waiting for the air to clear. In the first two weeks of December, the benchmark duration can be expected to lengthen roughly 0.25 years as a result of coupon payments and bonds rolling out of the index. We plan to adjust the portfolio duration accordingly.