Many longtime readers know that I’m a fan of gold.

And even though I haven’t added to my gold holdings since summer-2019 – back when it was sub-$1,300 an ounce – I do believe it has further upside.

Why?

Because – as usual – it’s a story about supply and demand.

I believe there’s a current mismatch between rising demand and diminishing supplies that are pushing prices higher.

And while pundits pay close attention to gold demand. It’s the fragile gold supply that’ll keep driving the momentum in the years to come.

Let me explain. . .

Gold Demand Continues To Soar – Especially Amid Aggressive Central Bank Buying

Now, while I believe too many analysts over-focus on the demand side, it’s still important to monitor.

So, how is gold demand looking?

Well, it appears very robust.

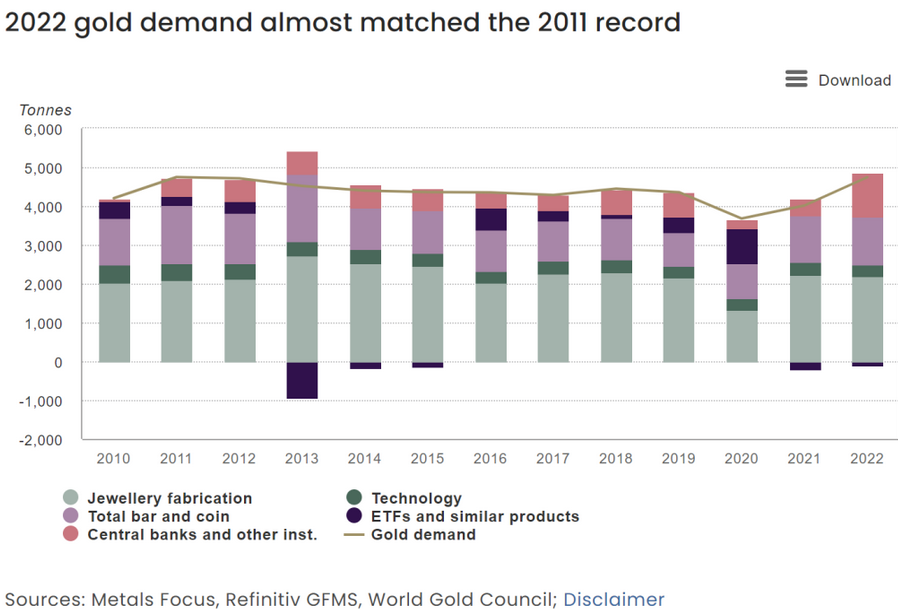

For instance – according to the World Gold Council – gold demand hit 4,740 tonnes in 2022 – marking an 11-year high and a 15.3% increase year-over-year.

Furthermore, gold also saw a record annual price average of $1,800 an ounce on the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA). And a nine-year high for retail bar-and-coin investment.

But what’s really driving demand for gold has been aggressive central bank buying. . .

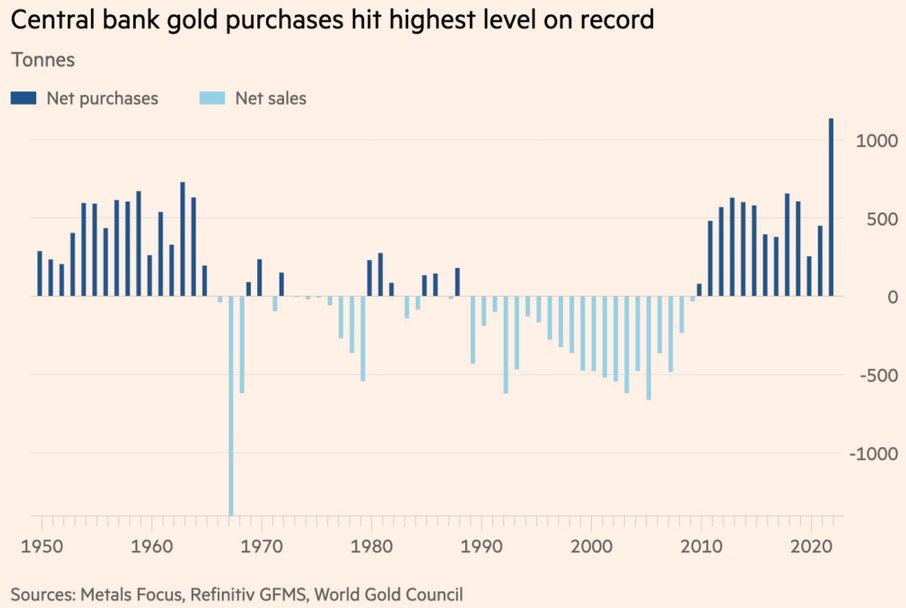

Since 2010, central banks around the world have been buying large amounts of gold (after net-selling for nearly the prior two decades).

But just last year, central bank gold buying hit 1,140 tonnes – its highest level on record. And a 152% increase in year-over-year terms.

Central banks in China, Turkey, Qatar, and Uzbekistan all bought large amounts of gold last year.

Why?

Because many central banks moved to diversify their reserves into gold amid greater geopolitical risk and higher inflation.

And it appears this trend will continue.

In fact, an annual poll of 83 central banks – managing a combined $7 trillion in foreign exchange reserves – showed more than 66% of those polled believed central banks would increase gold holdings in 2023.

So, it’s clear that gold demand looks to stay elevated (at least for now).

But as I stated above, I remain skeptical of analysts focusing solely on demand numbers.

That’s because demand is fickle.

Instead, I find it more worthwhile to focus on the supply side.

Or – putting it another way – gold demand can change quickly. But supplying it? That takes time.

Thus gold supply is where I believe the most upside remains. . .

Gold Mine Production Remains Relatively Weak – Meanwhile, New Discoveries Have All But Disappeared

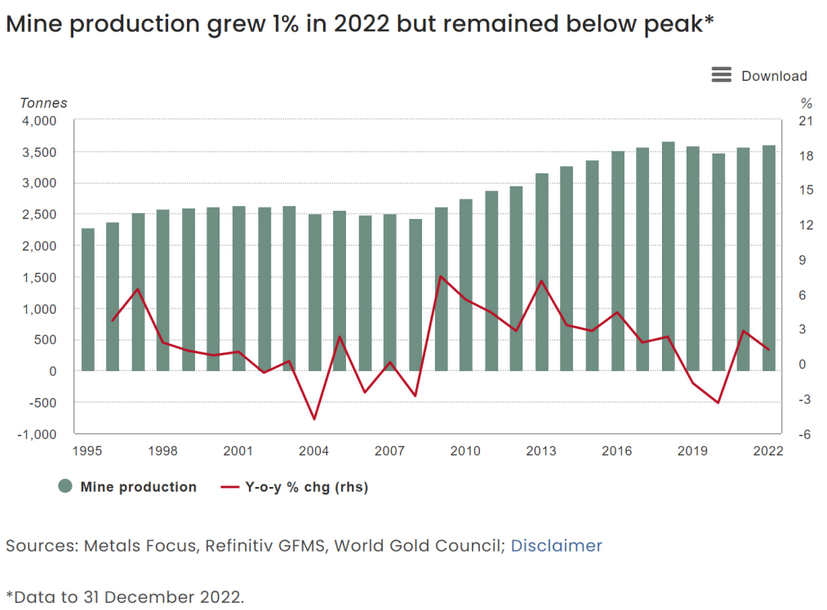

Since 2018, gold mine output has actually declined.

For instance, gold production hit 3,612 tonnes in 2022 – which is still about 1.5% less than what it was in 2018 (its peak).

You may be thinking, “What gives? Gold is hovering around record highs, yet mine supply is down?”

That’s a fair point.

But let’s take a look at history for a clearer answer.

See, when the price of gold soared post-2009, a large amount of mining capacity came online as entrepreneurs rushed in to soak up those profit margins.

But these mines took time to start producing (it takes roughly one-through-five years to develop a gold mine).

So by 2013 – when the gold price was already sinking – these new mines were coming online at the worst possible time.

Meaning they were effectively overproducing into a glut.

Or put another way – between 2012 and 2018, the gold price fell by 30%. But gold production still increased by around 20%.

This glut of overcapacity in gold mining went on for six years (until 2018-19).

Now, there are two big reasons why this happened:

1. A lower gold price meant companies had to produce more to make up for the lost income.

For instance, if the price of gold falls 50%, companies must double gold output to keep the same revenue (all else equal).

Now, this is sustainable if only a handful of gold companies scale up. But when they all do at the same time – it floods the market with supply.

And these newly built mines (or even current producers) aren’t going to just shut down. They have debt and liabilities they must service, which requires cash flow from producing.

This only further amplifies the over-capacity and glut problem.

2. Management faced a ‘prisoner dilemma’ – aka the concept describing a situation where two groups have competing incentives that lead them to choose a suboptimal outcome.

Let’s say ‘gold company A’ wants to scale back on supply to raise gold prices. Which makes sense. But how would the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) explain to shareholders that they’re scaling back, losing market share and profits to other gold miners that continue expanding? That CEO would most likely be out of a job.

Gold company A would suffer weaker earnings and a lackluster growth profile, leading to eroding valuations and angry shareholders.

Thus even though the prudent thing is for the majority of gold firms to decrease output in the face or lower prices, they can’t risk it knowing others may pounce.

So they’re all stuck over-producing into a glut (a sub-optimal outcome). And eventually, only the strong will survive – but that takes years to play out.

Put simply, over-capacity plagued the gold mining sector until 2018 – when peak gold output was finally hit – and majors finally threw in the towel. (In that chart above, notice how annual gold production growth finally fell negative in 2018 – the first time since 2008).

Since then, gold production has declined from its peak as marginal operations were closed and companies finally began scaling back.

Miners began focusing on operating margins and divesting by 2019 instead of expanding, drilling, and investing.

To put this into perspective – back in Q1-2019 – Fitch noted that, “despite the fact that prices are predicted to average $1,300/oz and that most major miners’ cash costs of production should remain comfortably below $900/tonne. The largest firms in the world are likely to remain committed to spending cuts in an effort to reduce debt loads, and continue to pursue a strategy of improving both operational and cost performance. . .”

But there’s a catch to this. . .

Because any commodity producer – such as gold mining – has finite reserves available.

Meaning that anything that’s pulled out must be replaced or the mine will run dry.

And as companies began scaling back drilling and exploration budgets after 2012, it only amplified the shortage of quality gold discoveries.

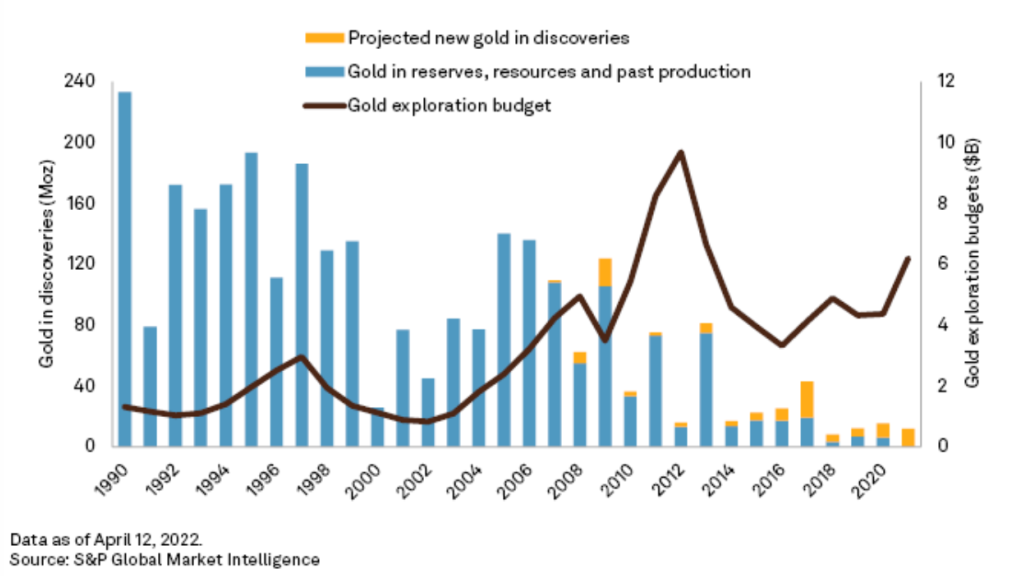

For instance – S&P Global wrote back in mid-2022 that there’s been a steady and sharp decline in major gold discoveries over the last 30+ years. . .

But especially so since 2018.

In fact, only 28 of the 341 deposits analyzed were discovered over the past decade – containing just 171.8 million ounces.

That means only 6% of all gold since 1990 was discovered between 2012-2022.

Meanwhile, exploration budgets have increased substantially in that same period. Peaking in 2012 at $10 billion but now down to ~$6 billion as of 2022 – a 40% decline.

And although it’s true that exploration budgets have increased since 2020 – it’s still at a nine-year low.

This tells us that the cost of gold exploration has increased rapidly at a time when there’s a shortage of quality discoveries.

This is a serious issue since the gold mine supply is essentially fueled by discovering new deposits.

But on top of the relatively weak gold production (still below 2018 peak levels) and dearth of quality gold deposits – miners are suffering from eroding reserves.

S&P Global published a piece in mid-2020 highlighting that between 2010 and 2019, sixteen of the world’s 20 largest gold producers saw overall years of production decline. And that these producers held roughly 668 million ounces of gold in reserves by the end of 2019. Sufficient for just 14 years more of production (at 2019 output levels).

The report further notes that during this period, most miners relied mainly on acquisitions to replenish reserves or bolster production. But in hindsight, some of their largest deals are now viewed as “overpriced, ill-timed or ultimately unfruitful.”

This isn’t surprising as during booms, acquisitions go far above “fair” value and must be written down or absorbed later.

But what’s interesting is that almost three-quarters ($51 billion) of the 20-major miners’ total expenditures went to acquisitions, accounting for 53% of reserve growth. Indicating that they depended more on costlier acquisitions than exploring for such reserves.

This makes sense as drilling and exploring for ever-fewer potential deposits is riskier than paying a premium for proven reserves to develop.

Now, gold producers will likely continue upgrading reserves at current mines and further absorb smaller gold producers.

But the fact remains that the lack of new deposits will eventually knee-cap this strategy.

Thus I expect the constrained supply side should keep gold prices elevated – if not pushed higher.

And until we see substantial renewed investment, new major discoveries, and expansion in gold mining, this trend will most likely deepen.

Conclusion

While gold has held up remarkably well in the face of higher interest rates over the last year – the market remains a fickle beast.

Gold demand can change quickly based on retail investment and central bank appetite. For instance, some may sell gold when they need to raise dollars, such as Turkey selling roughly 200 tonnes between July-2020 and January 2022. (Albeit they’ve re-purchased 150 tonnes over the last year).

Meanwhile, supply has long lag effects and can get stuck in amplifying feedback loops (such as overproducing into a glut or underproducing into a shortage).

But I believe regardless of demand rising much more, the issues facing the supply side bolster gold’s upside.

Miners are dealing with diminishing reserves, a shortage of new deposits, and a focus on operating margins that have curtailed marginal output and crippled long-term supply pipelines.

And until this momentum changes – such as a surge in exploration and production capacity – gold should remain higher for longer.

So – as always – be wary of those only focusing on demand-side fundamentals.

Because I believe the supply side tells us much more.

*NOTE: longtime readers may remember I wrote about the same sinking output in the uranium market in 2018. Which finally ended the multi-year bear market and fueled my long uranium positions. You can read it here if interested.