Ready for inflation?

Just days after Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin reassured markets that a trade war between the U.S. and China was “on hold,” the Trump administration announced that it would be moving forward with plans to impose 25 percent tariffs on as much as $50 billion worth of Chinese exports to the U.S. Beijing has already suggested that it will retaliate in kind.

The White House also reinstated tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum from Canada, Mexico and the European Union (EU) after allowing earlier exemptions to expire. Again, there’s a big chance the U.S. will see some sort of tit-for-tat response.

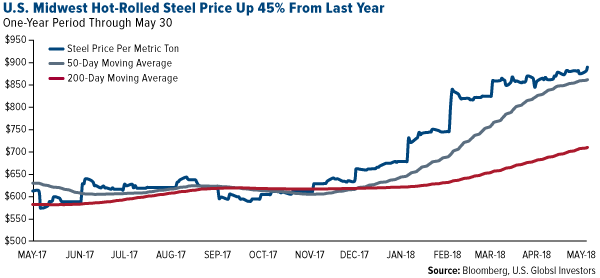

Steel prices are already up 45 percent from a year ago. The annual change in the price of a new vehicle in the U.S. has been dropping steadily since last summer, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, but with the cost of materials set to rise dramatically, we could see a price reversal sooner rather than later.

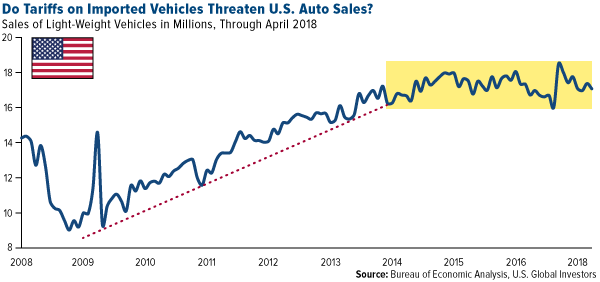

Next up, the U.S. government could slap steep tariffs on imported automobiles—and possibly even ban German luxury vehicles outright, according to a report by German business news magazine WirtschaftsWoche.

These decisions, if fully implemented, will have a multitude of implications on the U.S. and world economies. What I can say with full confidence, though, is that prices will rise—for producers and consumers alike—which is good for gold but a headwind for continued economic growth.

You Can’t Suck and Blow at the Same Time

Let me explain. I’ve often said that middle class taxpayers elected Trump president by and large to take on entrenched bureaucrats, cut the red tape and streamline regulations. People are fed up.

A study last year by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that government workers not only earn more on average than private-sector workers with similar educational backgrounds, they’re also guaranteed health, retirement and other benefits. Trump responded to these concerns by signing an executive order that eased the firing of federal workers.

He’s kept his word in other ways. Since being in office, he’s already eliminated five federal rules on average for every new rule created, according to the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). He’s weakened Obamacare and Dodd-Frank, not to mention slashed corporate taxes.

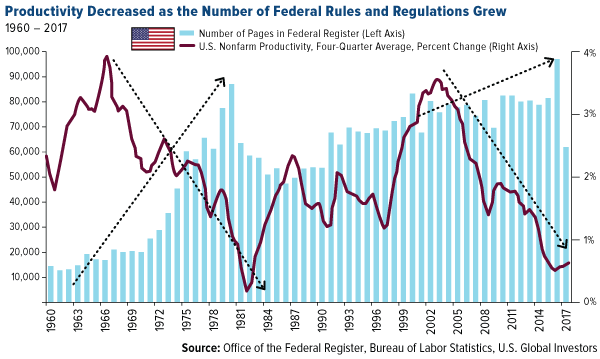

In 2017, the number of pages in the Federal Register, the official list of administrative regulations, dropped to 61,950 from 97,069 the previous year. This is especially good news for productivity. Research firm Cornerstone Macro found that Americans were more productive when there were fewer rules, less productive when there were more rules.

These are all positive developments that should help boost the economy. The problem is that they could be undermined by tariffs, which are essentially regulations. We believe government policy is a precursor to change, and history suggests that rising tariffs and regulations hurt the economy.

Consider automobiles. U.S. automakers are the second largest consumer of steel following construction. In March, the Wall Street Journal estimated that the tariffs could add at least $300 to each new vehicle sold in the U.S. And speaking to Bloomberg last week, a spokeswoman for the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers said the tariffs on steel and aluminum imports will make cars more expensive. “These tariffs will result in an increase in the price of domestically produced steel—threatening the industry’s global competitiveness and raising vehicle costs for our customers,” Gloria Bergquist said.

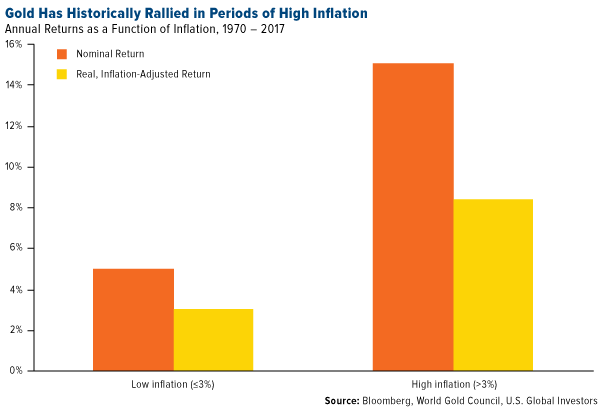

Higher Inflation Has Historically Meant Higher Gold Prices

The good news in all this is that higher inflation has historically been supportive of the price of gold. In the years when inflation was 3 percent or higher, annual gold returns were 15 percent on average, according to the World Gold Council (WGC).

When gold hit its all-time high of $1,900 an ounce in August 2011, consumer prices were up nearly 4 percent from the same time the previous year. The 2-year Treasury yield, meanwhile, averaged only 0.21 percent, meaning the T-note was delivering a negative real yield and investors were paying the U.S. government to hang on to their money. This created a favorable climate for gold, as investors sought a safe haven asset that would at least beat inflation.

CIBC: Major Gold Firms to Generate Strong Free Cash Flow and ROIC

Finally, I want to draw attention to an exciting research report released last week by the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC). I’m a huge admirer of the work CIBC does, especially that of Cosmos Chiu, director of precious metals equity research. Chiu and his team write that the “future looks brighter” for gold equities on improved free cash flow and return on invested capital (ROIC).

Both factors are among our favorites. I recently shared with you a chart that shows that, over the past 30 years, ROIC outperformed other factors (link, above) by as much as one and half times. With gold trading near $1,300 an ounce, producers are currently posting positive margins, according to CIBC. As a result, every stock in the bank’s large-cap universe, with the exception of Kinross (NYSE:KGC), is expected to generate positive free cash flow through 2019.

Royalty/Streaming Companies Deliver the Profits

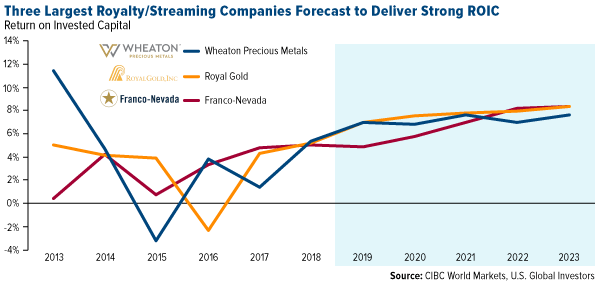

The bank has even better news for royalty and streaming companies, particularly Franco-Nevada (NYSE:FNV), Royal Gold (NASDAQ:RGLD) and Wheaton Precious Metals (NYSE:WPM). For one, the three big royalty names delivered combined shareholder returns of 6.2 percent between 2013 and 2017, outperforming both senior producers and physical gold.

Now, CIBC forecasts the royalty group will generate strong ROICs, “steadily inching higher over the next decade… to average between the 5 percent and 8 percent mark from 2018 – 2023.” ROIC measures how well a company can turn its invested capital into profits.

Disclosure: All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product. Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication.