Investing.com’s stocks of the week

Many longtime readers know that I’ve talked often about there being a global savings glut issue. Or, said another way, there’s been far too much liquidity in the global financial system with a lack of attractive investments.

Thus, I believe it’s safe at this point to say that credit is not the problem. Rather, the issue is banks and other lenders finding places to put it all.

This is the main reason why global central bankers have been stuck pushing on string with their aggressive easing policies.

Meaning: they can print and ease as much as they want (which they have). But if it isn’t getting into the main-economy (which it hasn’t)—then all it’s doing is fueling a savings glut, excess speculation, and further inequality.

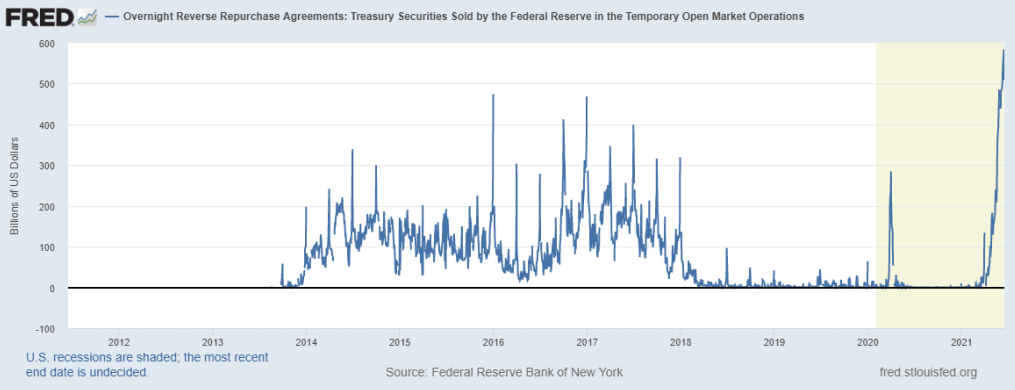

And now we are seeing another key symptom of this savings glut issue in the Federal Reserve’s overnight-reverse-repo facility (aka the RRP facility). . .

(To give some context: the RRP facility is known as the ‘last resort’ for banks and money-markets. It’s a place to park excess cash for a short-duration—usually overnight—for 0% interest. This indicates that these institutions would rather shelve that money for zero-return instead of paying interest to keep that cash in-house).

Over the last few weeks, major banks and financial firms have shoveled a record amount of excess cash—nearly $600 billion—into the RRP facility.

(Note that is the exact opposite of the dollar shortage situation that was brewing 2019—which I wrote about here).

And—to make matters more interesting—these same banks have asked large depositors (such as corporate accounts) to take their money elsewhere since they don’t know what to do with it.

Keep in mind that, typically, high deposit rates are what banks want—giving them fuel to make more loans. (Remember: the difference between what the bank lends cash out for and what it pays to depositors is their profit).

But, the problem today is that banks aren’t making as many loans. . .

In fact, to put this into perspective: total loans from banks were just 61% of all deposits as of late-May. Down from 75% in February last year—a multi-decade low.

(A big reason for this decline in loans is that corporations can access cheaper money from yield starved investors directly. Either through issuing bonds or shares).

Thus, as new loans diminish while deposits soar, margins have decreased at banks. And without the RRP facility, various short-term market rates would most likely be negative (through depositor fees or lower yields) amid this savings glut.

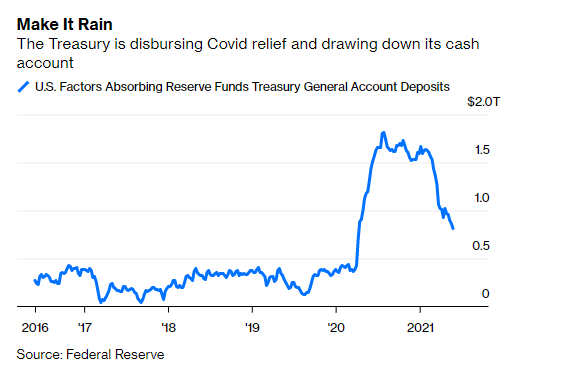

And—making things worse—the Treasury General Account (aka the governments bank account at the Fed) has been liquidating over the last 6-months. . .

(Meaning: the Treasury is spending the money in their account via stimulus payments to citizens, local and state governments, etc. Which then ends up in commercial banks and money market funds. Making the glut even worse).

Therefore, it’s no surprise then why yesterday the Fed raised their overnight-RRP rate by 0.05% to help prevent rates from going negative as liquidity overwhelms the banking system.

But—this glut still has potential to get far worse. . .

That’s because the Fed continues buying $120 billion-a-month in bonds via QE (quantitative easing). Thus far totaling over $2.5 trillion since the pandemic began in early-2020.

This puts the banking system in a truly a peculiar situation:

On the one hand, the Fed’s busy pumping huge amounts of cash into the banking system (via QE).

But on the other hand, investors and banks are giving this cash back to the Fed via the RRP facility. . .

So—in summary—there’s a savings glut that’s creating greater distortions and fragility in the banking system.

And while the Fed continues pumping money into the system hoping it will spur new investment and growth, all it’s done is create waves of unintended consequence (such as malinvestment, moral hazard, further inequality, and asset bubbles).

That’s because there’s a global lack of investments—a structural problem—which can’t be cured by the Fed’s cyclical tools. . .

And while many believe that new loans will pick up as the economy returns to normalcy, thus fueling inflation and growth, I remain skeptical.

Why?

Because this structural savings glut has plagued the global economy for decades (since the 1980’s—but I’ll write more on this later). . .

Thus I expect more deflation, lower growth, and lower rates. Because as noted above, it’s not the supply of money that’s the problem. But the lack of places where to put it all.

And until this changes, it’s hard to believe that anemic global growth trend will also. . .

For instance: as we saw first with the Bank of Japan—followed by the European Central Bank. Pumping credit into places where there’s diminished demand is more harmful than anything.

But as usual, only time will tell. . .