Last week, European Central Bank (ECB) head Draghi talked about the de-coupling of the ECB and the Fed’s policies, of policy divergence. Lots of pundits have suggested the same. With due respect to their views, my analysis of the data suggests they are wrong. If you own dollars, the euro or gold, you might want to pay attention to this one.

What could possibly be wrong with conventional wisdom? It shouldn’t be a surprise that pundits merely regurgitate what others say. But why would Draghi join the fray? It turns out, he has a vested interest in the ‘policy divergence’ view, as promoting it might help to weaken the euro. If indeed the U.S. interest rate path is upward, while rates in the Eurozone stay lower for longer, it might justify a weaker euro.

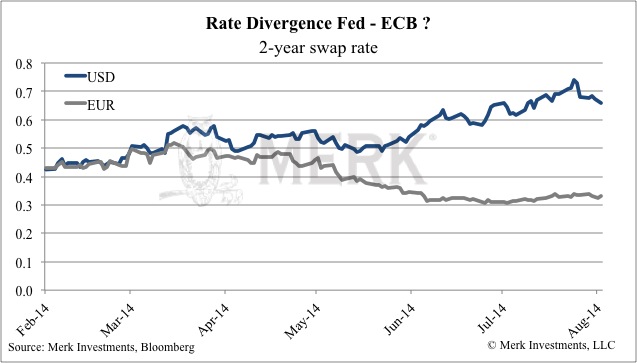

So, sure enough, at first blush, they have a point:

The above chart compares the “2-year swap rates” for the U.S. dollar and euro. In essence, this chart shows the market expects short-term rates to be higher in the US than in the Eurozone over the next two years. It also shows that the gap has generally been widening in recent months. But this only tells us part of the story.

That’s because the above chart reflects nominal rates to be rising, but reflects nothing about real interest rates (i.e., interest net of inflation).

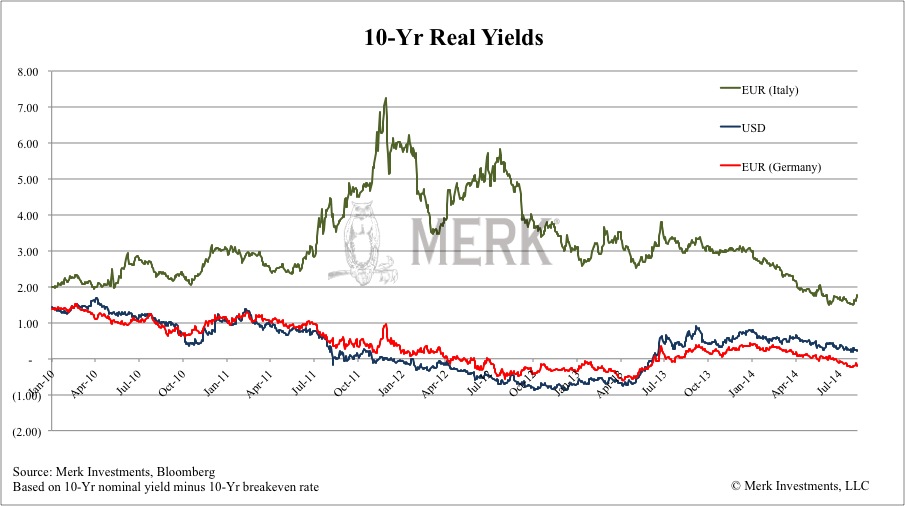

If we only looked at German 10-Year real yields versus U.S. 10-Year real yields, U.S. yields are higher. However, the Eurozone is more than just Germany (and the ECB’s mandate is to keep Eurozone inflation close to, but below 2%). Only Germany, France and Italy have inflation protected securities akin to the TIPS available in the U.S. that are commonly used to determine market expectations for real yields. As the Italian real yield line above suggests, a blend of Eurozone yields will be higher. On a real basis, Eurozone 10 year yields are higher than U.S. yields.

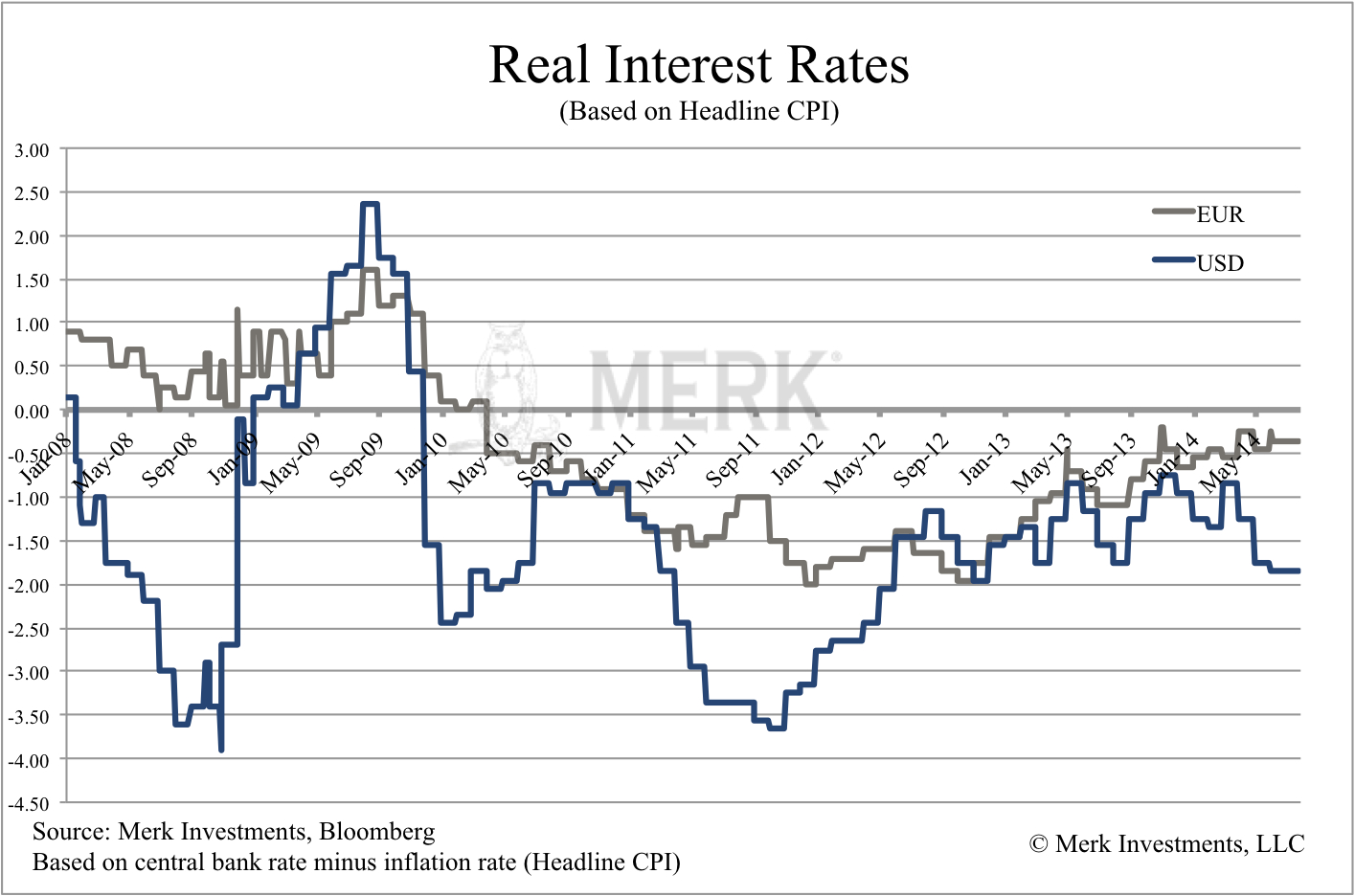

While looking at 10-year real yields is an interesting exercise, let’s take the discussion closer to the present where current prices are determined:

The chart above shows that real interest rates in the U.S. are not only lower than in the Eurozone, but also that the divergence has been growing in the opposite direction of nominal rates. The Eurozone is holding steady, whereas U.S. real rates are falling.

So what is it now? In this currency war, one might be excused for not recognizing who is the most dovish of them all. Basically, the market currently prices in that nominal interest rate hikes might indeed be coming. But our interpretation is also that inflation, at least in the short-term, is higher in the U.S. than in the Eurozone. If inflation indeed is picking up and central banks stay put, they will be “behind the curve,” meaning real interest rates may continue to be negative for a very long time.

Now let me ask you this: is the U.S. or Eurozone more vulnerable to inflation? In the U.S., the banking system is much healthier than in the Eurozone. While Fed Chair Yellen preaches we can’t have inflation given the slack in the economy, former Fed Chair Volcker has said the inflationary experience of the 1970s had proven this argument wrong.

Contrast that with the Eurozone where many banks continue to be impaired. While policy makers work hard to improve the banking system there, the short of it is that – at least in our assessment – it will be much harder for inflation to gain a foothold.

Having said that, if we do get inflation to gain a foothold in the U.S., I have little doubt that it will also be exported to other regions in the world. However, our analysis suggests that inflation may have a much easier time to build in the U.S. than Eurozone.

So while pundits, experts, policy makers – you name it – jump on the bandwagon of a U.S. “exit” and “policy divergence”, we can’t join the fray:

• An environment where real interest rates are negative, and trending to be more negative, and where Fed Chair Yellen has indicted she will be slow in raising rates is not an “exit.” In our assessment, this is financial repression as far as the eye can see.

• We see real interest rates higher in the Eurozone than in the US for the foreseeable future, even as nominal rates might be diverging. Nominal rate increases make for good headlines, but might make for poor investment decisions.

In the introduction, we mention implications for the dollar, euro and Gold. If real rates stay negative for an extended period, this may bode well for gold and poorly for the U.S. dollar. And while Draghi has had the upper hand in weakening the euro for a couple of weeks now, this streak may come to an end.