Continued concern over the financial health of Europe -- and Greece, Italy, and Spain, in particular -- sent U.S. Treasury yields plummeting last week, in the case of the ten-year U.S. Treasury, to levels not seen since the end of World War II.

The ten-year Treasury closed on Friday, May 25 at 1.73%, and by close of business on Friday, June 1 it was 1.45%, a drop in yield of 28 basis points. The thirty-year Treasury yield went from 2.84% to 2.52%, a drop of 32 basis points. This continued a trend of plunging yields in the month of May. On a comparative basis, tax-free muni yields (as measured by the Municipal Market Advisors scale) barely budged, dropping 9 and 7 basis points, respectively.

Overbought Treasuries

This is another of those cases where the cheapness of the municipal bond market is, in our opinion, being dictated by an extremely overbought Treasury market. However, the defensiveness of the tax-free market is baked into the absurdly high ratios of munis to Treasuries.

This is another of those cases where the cheapness of the municipal bond market is, in our opinion, being dictated by an extremely overbought Treasury market. However, the defensiveness of the tax-free market is baked into the absurdly high ratios of munis to Treasuries.

Ample Supply

The important point to note is that most new issues coming to market, and many secondary issues, are trading MUCH cheaper than quoted scales. This reflects differing quality of bonds, of course, and relative supplies of certain states; call protection also figures into the relative yield levels. Certainly, municipal issuers are keen to the overall drop in interest rates and have stepped up supply (of new issues, as well as the refunding of older, higher-coupon issues from ten years ago that are currently callable. The Bond Buyer visible supply has risen from $6.6 billion to $12 billion in the course of a week, as well -- this will also keep ratios extremely high for another week or two.

Here is an example of the above.

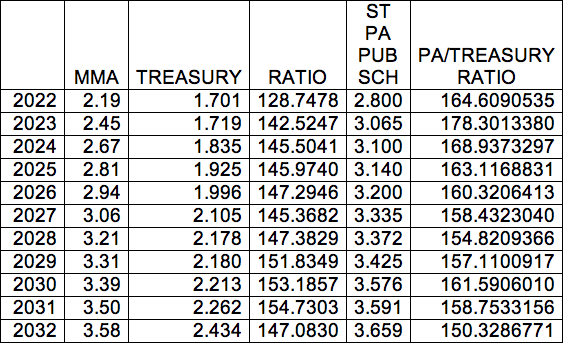

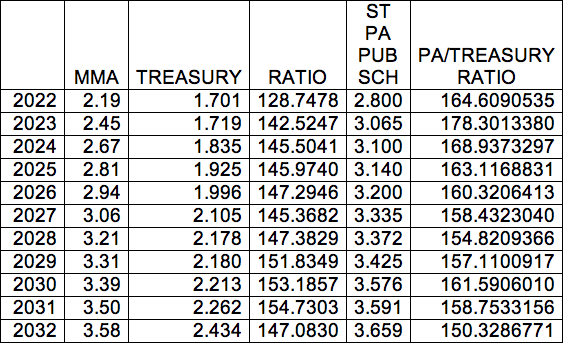

In this table we compare the muni/Treasury yield ratios using the Municipal Market Advisors AAA scale. We also compare it to a Pennsylvania School Building Authority deal from last week (A1 Moody’s, AA- Standard and Poor’s), and an appropriation-backed bond from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Cumberland bought some of the 2025 bonds at what amounted to a 3.18% yield after a concession. This compares to a yield ratio basis of 187% versus the ten-year U.S. Treasury yield and 165% versus the 13-year U.S. Treasury yield. And, three days later, the ratios are now cheaper.

To put the ratios in perspective, the ten-year muni/Treasury ratio at the end of the first quarter of 2010 was approximately 85%. Then concern about Greece hit and ratios have not been the same since. Another way to look at this cheapness is to view it through the prism of how muni bonds should react if the ratios go back to longer-term, historical norms.

Case In Point

In the Pennsylvania example, let’s assume that in three years the economy has improved and the ten-year bond has risen from its current level back to 3.5% (an increase of over two hundred basis points). And, the thirteen-year Pennsylvania School Board bond has gone back to a 90% ratio to the ten-year bond. That would be a 3.15% yield, approximately where it is priced today. In other words, the municipal bond should stay relatively unchanged while a thirteen-year U.S. Treasury bought last week at 1.92% would lose approximately 13½ points if it were priced at a 3.50% three years from now. That 13-point advantage on a severe rise in rates is what demonstrates the current cheapness of the market.

On a relative basis, it’s a giveaway.

The ten-year Treasury closed on Friday, May 25 at 1.73%, and by close of business on Friday, June 1 it was 1.45%, a drop in yield of 28 basis points. The thirty-year Treasury yield went from 2.84% to 2.52%, a drop of 32 basis points. This continued a trend of plunging yields in the month of May. On a comparative basis, tax-free muni yields (as measured by the Municipal Market Advisors scale) barely budged, dropping 9 and 7 basis points, respectively.

Overbought Treasuries

This is another of those cases where the cheapness of the municipal bond market is, in our opinion, being dictated by an extremely overbought Treasury market. However, the defensiveness of the tax-free market is baked into the absurdly high ratios of munis to Treasuries.

This is another of those cases where the cheapness of the municipal bond market is, in our opinion, being dictated by an extremely overbought Treasury market. However, the defensiveness of the tax-free market is baked into the absurdly high ratios of munis to Treasuries.

Ample Supply

The important point to note is that most new issues coming to market, and many secondary issues, are trading MUCH cheaper than quoted scales. This reflects differing quality of bonds, of course, and relative supplies of certain states; call protection also figures into the relative yield levels. Certainly, municipal issuers are keen to the overall drop in interest rates and have stepped up supply (of new issues, as well as the refunding of older, higher-coupon issues from ten years ago that are currently callable. The Bond Buyer visible supply has risen from $6.6 billion to $12 billion in the course of a week, as well -- this will also keep ratios extremely high for another week or two.

Here is an example of the above.

In this table we compare the muni/Treasury yield ratios using the Municipal Market Advisors AAA scale. We also compare it to a Pennsylvania School Building Authority deal from last week (A1 Moody’s, AA- Standard and Poor’s), and an appropriation-backed bond from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Cumberland bought some of the 2025 bonds at what amounted to a 3.18% yield after a concession. This compares to a yield ratio basis of 187% versus the ten-year U.S. Treasury yield and 165% versus the 13-year U.S. Treasury yield. And, three days later, the ratios are now cheaper.

To put the ratios in perspective, the ten-year muni/Treasury ratio at the end of the first quarter of 2010 was approximately 85%. Then concern about Greece hit and ratios have not been the same since. Another way to look at this cheapness is to view it through the prism of how muni bonds should react if the ratios go back to longer-term, historical norms.

Case In Point

In the Pennsylvania example, let’s assume that in three years the economy has improved and the ten-year bond has risen from its current level back to 3.5% (an increase of over two hundred basis points). And, the thirteen-year Pennsylvania School Board bond has gone back to a 90% ratio to the ten-year bond. That would be a 3.15% yield, approximately where it is priced today. In other words, the municipal bond should stay relatively unchanged while a thirteen-year U.S. Treasury bought last week at 1.92% would lose approximately 13½ points if it were priced at a 3.50% three years from now. That 13-point advantage on a severe rise in rates is what demonstrates the current cheapness of the market.

On a relative basis, it’s a giveaway.