With one active year of raising rates and reducing its balance sheet behind them, and a second active year reversing all those actions, the Federal Reserve seems ready to go into hibernation and sleep through 2020.

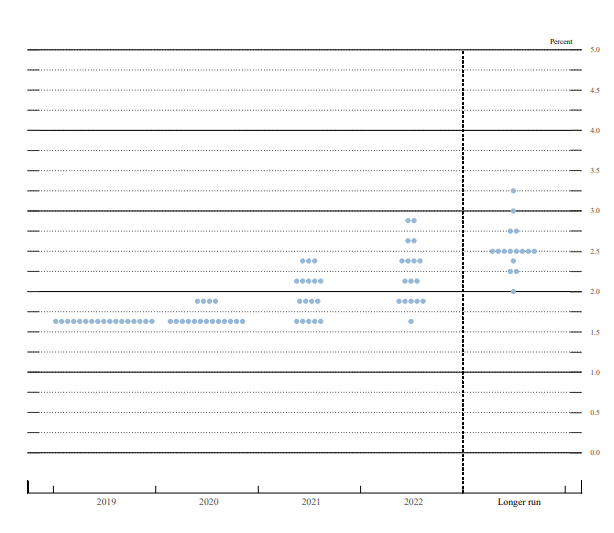

The quarterly dot-plot graph released Wednesday in connection with the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting showed a large majority of members, 13 out of 17, forecasting no change in the benchmark Federal funds rate next year from its current 1.50 to 1.75%. FOMC members are only predicting increases in the rate again once 2021 rolls around.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell didn’t have much to say at the press conference following the two-day meeting, which left rates unchanged after three successive quarter-point cuts. Given the Fed’s declared intention to pause, it’s difficult to imagine how he or journalists covering the events will fill the time in the eight press conferences scheduled for next year.

Current Monetary Policy Expansion Supportive

Some black swan could appear to puncture that tranquil scenario, but aside from a passing mention of monitoring global developments and the muted inflation outlook, the consensus statement simply affirmed the FOMC belief that current monetary policy supports continued expansion.

Still, out of idle curiosity, journalists repeated their standard questions of why inflation remains so muted even as unemployment continues to fall. Powell could only repeat his increasingly meaningless refrain that policymakers remain committed to reaching their target of a symmetric 2%—meaning they would overshoot it to get a solid average of 2%.

The Fed chair said he personally would grow concerned about inflation only if it was consistently fixed at the target. While the consumer price index for November released this week was up 2.1% on the year, the core personal consumption expenditures index used by the Fed was up only 1.6% in October, the latest available.

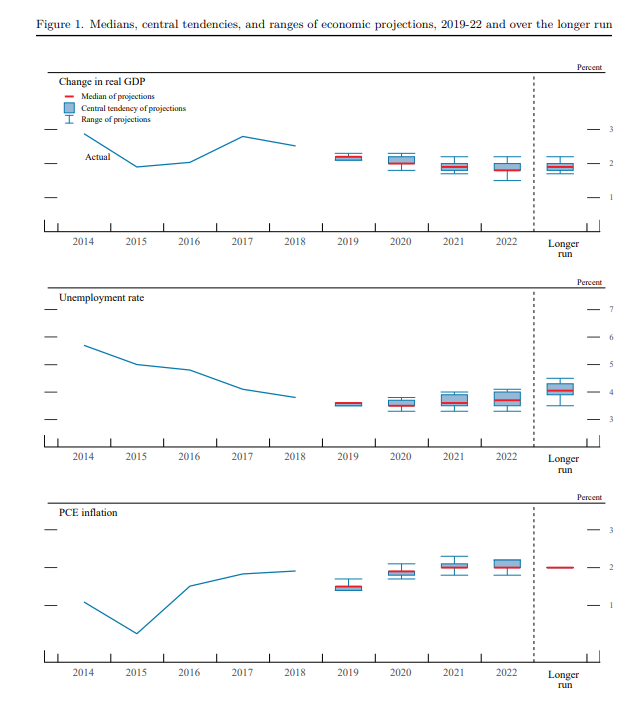

FOMC members projected core PCE inflation rising to 1.9% next year from 1.6% this year (down from the 1.8% they projected in September) and 2.0% in 2021 and 2022. Of course no one knows what inflation will be two years from now, and the forecasts only reflect how things look from here. The Fed considers inflation expectations to be well anchored.

One telling statistic in the projection materials was the so-called longer run forecast for unemployment, which shows the range policymakers expect will be consistent with stable prices in an ideal future. That range was 3.9% to 4.3% in Wednesday’s projection, compared with 4.2% to 4.5% a year ago, and 4.4% to 4.7% previously. For reference, the November unemployment rate reported last Friday was 3.5%, down from 3.6% in October.

When asked about unemployment and how historically low numbers still don’t push up inflation, all Powell could say was there must be more slack in the market than we realized. Without any upward pressure on wages, it would not be appropriate to call this a tight labor market, he said.

Where does all this leave investors? Likeliest answer: looking somewhere else for signs of where things are going. Having done what damage they could in 2018 and repaired most of it in 2019, Fed policymakers seem content now to sit back and observe events for the foreseeable future.