The new coronavirus is unfortunately deadly not only for humans but also for the global economy. The central banks have shot their bazookas, but the monetary policy is helpless during pandemics with their supply disruptions and self-quarantine that effectively freezes the economic activity. Interestingly, even the central bankers seem to acknowledge their impotence. As Jerome Powell said during his recent press conference:

We don’t have the tools to reach individuals and particularly small businesses and other businesses and people who may be out of work... we do think fiscal responses are critical.

It didn’t take long to persuade the governments to intervene and increase their spending. For example, Spain announced a $220B stimulus package or almost 16 percent of its GDP. The UK unveiled even larger stimulus: an unprecedented $400 billion financial rescue package, amounting to almost 15 percent of GDP, to “support jobs, incomes and businesses”. Germany went even further: the country authorized its state bank, KfW, to lend out as much as $610 billion, or almost 16 percent of GDP, to companies to cushion the effects of the coronavirus.

Trump has already signed two packages, but worth only $108 billion. But do not worry: Americans have not said their last word yet. Republican and Democratic senators have reached a deal on a roughly $2 trillion stimulus package. Yes, you read it correctly. Two plaguy trillions! But if you think it’s a lot, you are wrong! In terms of the US GDP, two trillions is ‘merely’ 9.4 percent. So, don’t worry, there is room for further stimulus if needed.

Will that mammoth fiscal stimulus help? Well, it depends – the devil is in the details. A lot depends on what the governments will spend money on. The expenditures on healthcare and research on a vaccine are desperately needed, so even fiscal hawks (like us) would not complain. But, it can’t turn out the F-35 way and also let’s say that funding infrastructure projects would not be too helpful right now. You see, this is a unique situation in which the whole economies freeze out in order to flatten the curve and prevent the healthcare system from collapsing. But when firms do not operate, they have no revenues. Without revenues, people do not have wages. Without wages and revenues, loans are not repaid. Without repayments, the banking system collapses – and the whole system goes down like a house of cards. So, some support is needed to prevent that – so that people could smoothly pay their obligations.

Whether the easy fiscal policy will be helpful or not – it remains to be seen. But the recent unprecedented fiscal stimulus will have one very important consequence. The fiscal deficits will soar. Forget about austerity, surpluses or even a balanced budget. So, public debts will necessarily follow suit.

Why is it important? Well, global debt levels were already sky-high. In Q3, the global debt, which comprises borrowings from households, governments and companies, grew to $253 trillion, or to over 322 percent, the highest level on record. In many countries, public debt will soar to unstable levels.

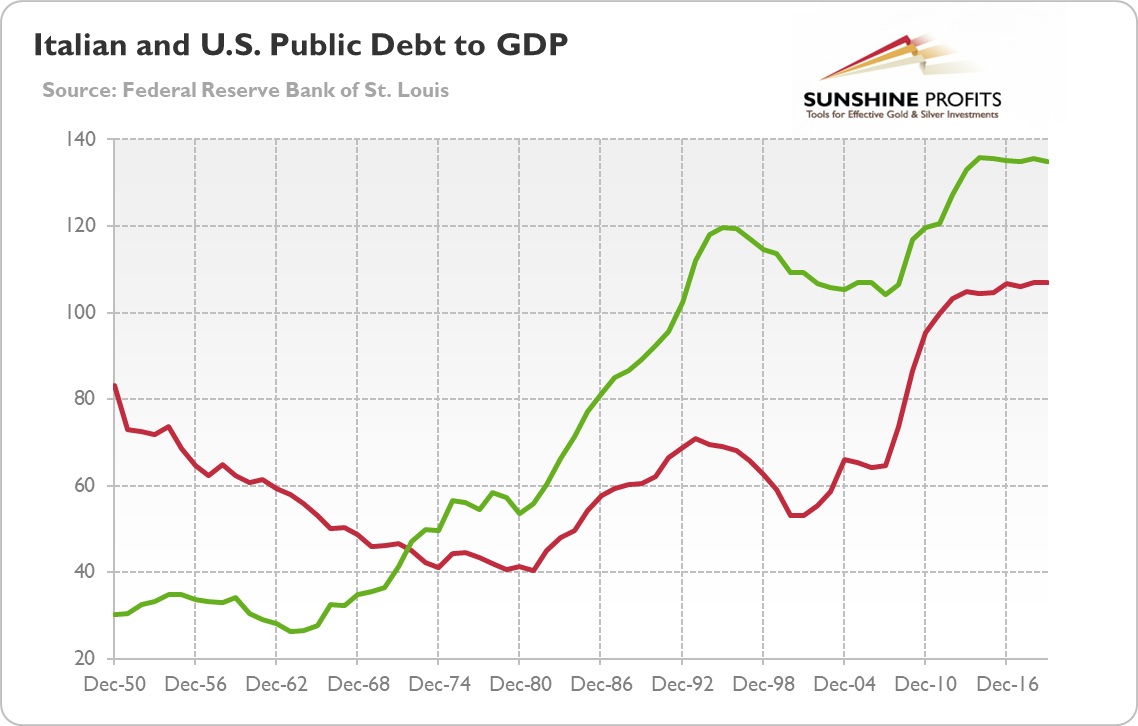

Let’s take Italy, whose economic fundamentals have been already poor: we mean here fragile banking system, growth stagnation and high public debt (see the chart below). Now, as the most affected European country by the virus, with the highest number of cases and fatalities, and the lockdown of its economy, Italy will enter a grave recession (the economy is expected to shrink by 5 percent at least), while its public debt will surge from 135 to above 140 percent of the GDP, or even more – as a reminder, Italy’s public debt went up more than a few percentage points in a single year of 2009 (from 106.5 to 116.9 percent of GDP).

Other southern countries will also face the reemergence of the sovereign debt crisis. This time Greece’s debt-to-GDP starts at over 180 percent, compared with 146 percent in 2010; Spain at 95 percent vs. 60 percent; Portugal at 122 percent vs. 96 percent; and France 98 percent vs. 85 percent. And private debts have also increased over the last years!

Chart 1: Italian public debt (green line, as % of GDP) and U.S. public debt (red line, as % of GDP) from 1950 to 2019.

The US is less indebted and not so badly hit by the COVID-19 (at least so far), but its economy is also forecasted to shrink in 2020. The combination of lower GDP and tax revenues with higher public expenditures will balloon the deficit and federal debt from slightly above $23 trillion, or 107 percent of GDP, in 2019 to almost $26 trillion, or more than 120 percent of GDP, in 2020.

Now, it means that we have a serious debt problem. How all these countries could repay all their debts? Well, they could increase taxes. It might happen in the US if a Democrat takes over the White House. However, taxes are already high and unpopular. So, the governments could also accelerate economic growth – but it is rather unlikely given the pre-pandemic trends and the accelerating response. And if they hike taxes, the growth will not speed up for sure. So, the only remaining – and more probable from the historical point of view – option, is it to inflate the debt. Financial repression with corralling mandatory investments into “safe” assets that are guaranteed not to keep up with the real or massaged inflation data.

With higher inflation, the real value of government debts will be lower. And the central banks have already eagerly started to buy government bonds with newly created reserves. It means that one of the important implications of the current pandemic and following policy response will be higher inflation. Perhaps not immediately, as the negative demand shock will create some deflationary pressure (although the negative supply shock creates inflationary pressure), but we should not neglect the threat of inflation. It means only one thing: when the dust settles and investors realize what is happening, they will turn to the ultimate inflation hedge – gold.

Disclaimer: Please note that the aim of the above analysis is to discuss the likely long-term impact of the featured phenomenon on the price of gold and this analysis does not indicate (nor does it aim to do so) whether gold is likely to move higher or lower in the short- or medium term. In order to determine the latter, many additional factors need to be considered (i.e. sentiment, chart patterns, cycles, indicators, ratios, self-similar patterns and more) and we are taking them into account (and discussing the short- and medium-term outlook) in our trading alerts.