Big Picture, I've touched on the potential for the Fed trapping themselves for at least a year. As usual, somebody said it better, so today I borrow from the bright people at SoberLook.com.

Low inflation creating a QE trap

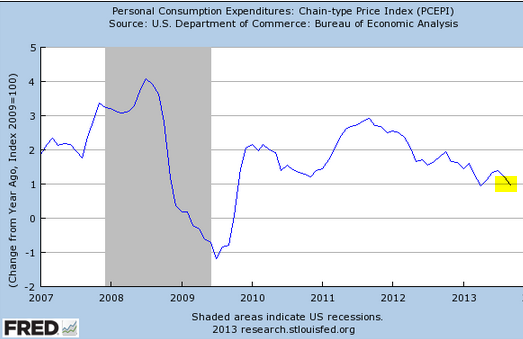

Scotiabank: - The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation — the price deflator for total personal consumer expenditures — came in at +0.9% y/y in September. We feel that markets are underestimating the importance of this observation to the Fed. That is tied with April for the softest inflation reading since October 2009 when the US economy was just beginning to emerge from recession.

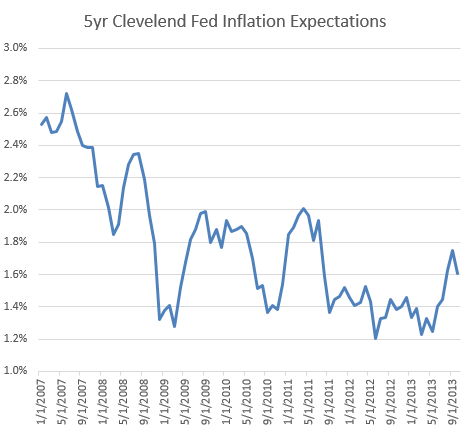

The forward looking inflation measure derived from TIPS yield (breakeven), has now also turned lower after a recent upward movement.

Similarly, we've seen a slump in commodity prices (see discussion), which is another signal of weak inflation readings.

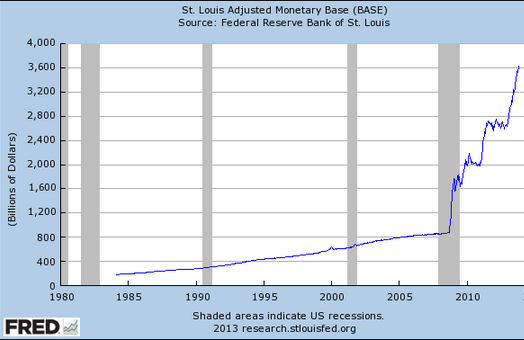

With inflation measures remaining this low, many argue (see story) that there is no rush to begin exiting the current monetary policy. The fact that the US monetary base is now 4.5 times greater than it was 5 years ago and capital markets are now fully addicted to ongoing stimulus does not seem add any urgency for these economists. The longer this goes on, the more difficult will be the exit, making it harder for the Fed to pull the trigger. Welcome to the QE trap.

See also:

Definition of 'Push On A String'When monetary policy cannot entice consumers into spending more money or investing in an economy, even if monetary policy is loosened to to put more money into peoples' hands. This term is often attributed to noted economist John Maynard Keyenes. |

|

Investopedia explains 'Push On A String'If the core demand doesn't exist to induce people to part with their money, it can't be forced through monetary policy. Trying to do so is like trying to "push on a string".Such a situation occurred during the Great Depression in the 1930s and in Japan during the late 1990s when interest rates were about 1%. This situation is sometimes referred to as a "liquidity trap" and explains why central bankers do not attempt to lower rates to levels approaching zero. To lower rates to this level would eliminate monetary policy's power to influence economic growth and consumption. |