Fed economists admits the obvious "Tariffs likely to kill jobs".

On occasion, Fed economists get things correct even if the voting members get things backward.

For example, New York Fed economists ask and answer the question: Will New Steel Tariffs Protect U.S. Jobs?

Consider this a guest post courtesy of New York Fed researchers Mary Amiti, Sebastian Heise, and Noah Kwicklis. As such I will dispense with blockquotes.

Will New Steel Tariffs Protect U.S. Jobs?

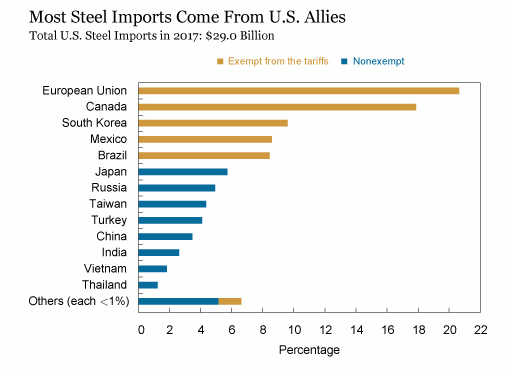

Although the tariffs were introduced under a national security argument, most U.S. imports are actually sourced from U.S. allies. The chart below shows that the largest supplier of steel to the United States is the European Union, accounting for more than 20 percent of its total steel imports. Countries for which the tariff is currently not applied account for 67 percent of U.S. steel imports, although this figure may change as negotiations with the currently exempt countries proceed. What is striking about this chart is the very small share, only 3.5 percent, originating from China. One reason for these trade patterns is that a large portion of imported steel, particularly from China, is already covered by special tariffs.

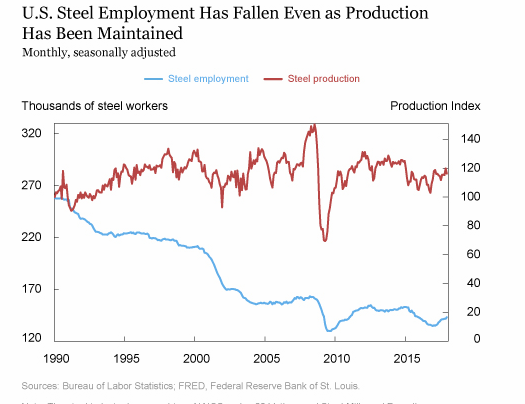

As the next chart shows, employment in the steel industry has been on a downward trend for decades. The industry, narrowly defined to only include workers where the steel tariffs apply, just employs 140,000 workers in total. In addition to import competition, rapid technological progress such as the introduction of mini mills has been blamed for displacing workers. As the chart shows, steel output has been fairly stable over the long run, and so output per worker has been on the rise. Since 2000, employment in steel production fell 33 percent while output per worker increased 43 percent (an average of more than 2 percent a year).

How do steel tariffs come into the picture? A tariff increases the price of imported steel, and it enables domestic steel producers to also increase their price. Research on markup adjustments more generally shows that a 10 percent increase in competitor prices leads to a 5 percent increase in domestic prices. With a 25 percent tax on imported steel, local steel producers can increase their markups and prices, and still stay competitive relative to foreign-produced inputs. This is the so-called protection that tariffs confer.

However, firms that are dependent on steel and aluminum inputs—both importers and non-importers—will face higher prices. Downstream domestic producers will have to increase their prices or reduce markups, which makes them uncompetitive relative to competing imports. Similarly, U.S. exporters that need steel or steel-related inputs will face higher input costs and will have to either increase export prices or reduce their profit margins. These effects could lead to lower employment in these steel-intensive industries and possibly plant shut downs. Researchers estimate that the number of jobs in steel-intensive industries, which they define as industries with steel inputs of at least 5 percent of total, is around 2 million—for example, manufacturers of auto parts, motorcycles, and household appliances.

It is in steel-related industries where jobs are likely to be at risk. To get a sense of the magnitude of the employment effects, we can turn to a similar episode in 2002 when President Bush introduced steel tariffs of up to 30 percent, although under different legislation. Studies of these tariffs found evidence of higher steel prices and job losses of 200,000 across the United States. This number is higher than the total number of workers employed by U.S. steel producers (187,500) at the time.

In principle, workers who lose their jobs in steel-related industries should reallocate toward jobs in other industries as the economy rebalances. If this process were frictionless, the impact on unemployment would be short-lived. However, research has estimated that average moving costs between sectors are high and therefore the reallocation process is slow. As firms in steel-related industries become less competitive, average wages in these industries are therefore likely to decline, and workers are likely to remain unemployed for some time.

The negative effects of the steel tariffs could be amplified if there is retaliation by other countries. China has already retaliated against the steel tariff by imposing tariffs on $3 billion in fruit and meat imports from the United States. Similarly, after President George W Bush imposed the 2002 steel tariffs the EU challenged his decision. The World Trade Organization declared the tariffs illegal and the EU was given authority to impose $2 billion in retaliatory sanctions against U.S. products.

In another case, when President Obama imposed a 35 percent tariff on Chinese tires in 2009, China immediately responded by imposing restrictions on U.S. shipments of chicken parts, which cost American chicken producers $1 billion in sales in 2011. Estimating the cost of a trade war is challenging because historically there have been so few. But one study does estimate the cost to be 3.2 percent of real world income.

Although it is difficult to say exactly how many jobs will be affected, given the history of protecting industries with import tariffs, we can conclude that the 25 percent steel tariff is likely to cost more jobs than it saves.

Mish Comments: Escaping the Wrath or Trump

That tariffs would cost US jobs was perfectly clear from the day Trump announced the tariffs.

I have commented on that aspect on numerous occasions, well before Trump announced the tariffs.

For the origins of the US trade deficit, please see Disputing Trump’s NAFTA “Catastrophe” with Pictures: What’s the True Source of Trade Imbalances?

Europe and Canada now struggle to escape the wrath of Trump.

Tariff Irony

China, which is barely impacted by new steel tariffs responded with its own tariffs that will cut US exports to China.

The question is not whether jobs will be lost, but rather how many US jobs will be lost as a result of these tariffs.

Meanwhile, the Bloomberg Econoday parrot offered this inane comment: "The details on tariffs are very welcome in what however is yet another subdued Beige Book, one that isn't signaling an increased pace of rate hikes for the Federal Reserve."

For tariff discussion, please see Fed's Beige Book Notes "Dramatic" Increases in Prices Due to Tariffs.

Rate Hike and Inflation Irony

Undoubtedly, the tariffs will slow the global economy, US included, yet the tariff-related price hikes have nearly everyone concerned over inflation.

Economists and market participants have inflation concerns ass-backward.

For rate hike and inflation irony, please see Belief in Inflation (And 4 or More Rate Hikes in 2018) Picks Up.