Despite last month’s slightly lower employment growth (jobs had a $151,000 net gain), it’s still highly probable the Fed will increase rates by year-end. While they are sensitive to the labor market developments, (several Fed governors have publicly stated that the jobs report is the single most important coincident data point for the Fed), they’re more apt to use the 3, 6 and 12-month averages for guidance. And with 3-month average gains of 232,000, a hike of at least 25 basis points is given. Yellen is not the only governor on board for an increase; recent speeches or public comments from Mester, George and Fisher also contain hawkish commentary.

One governor who may not be on board is Fed President Evans who recently discussed Larry Summers' secular stagnation hypothesis. Evans offered strong empirical support for this theory, beginning with the lower labor force participation rate. Fed researchers have documented two primary causes for this development: retiring baby boomers and the sharp decline in teenage employment.

But Evans goes one step further, explaining why this development lowers growth:

“The retirement of highly experienced workers mean that improvements in the quality of the work force are already contributing less to productivity growth than they have in the past.”

Employees develop industry specific knowledge over their lifetime which they use to increase their productivity. This knowledge is lost as people retire. There is no easy way to replace it; instead, it must be “re-developed” over the careers of those currently in the labor force. This takes time lowering the overall lower pace of growth.

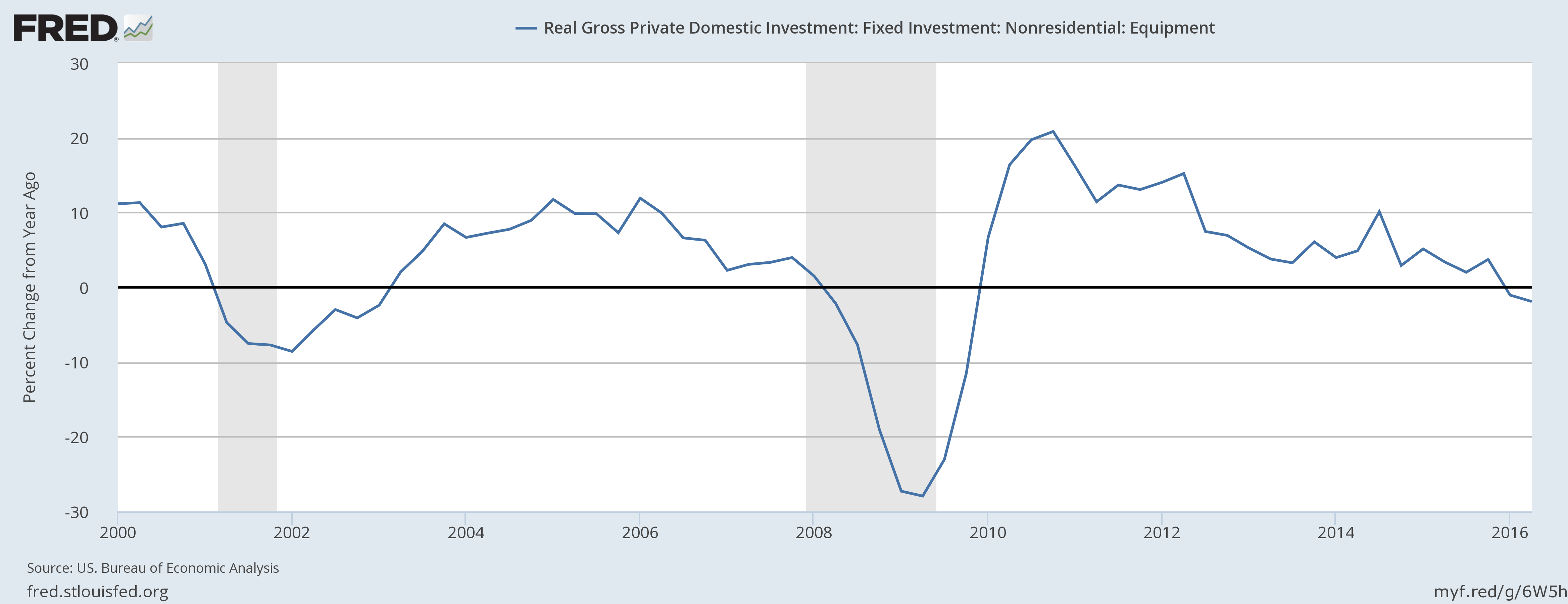

A second cause of secular stagnation is weak investment, which is placed into recent historical context by the following graph:

Investment spiked after the recession in response to standard post-recession incentives such as accelerated depreciation rules and the natural obsolescence of then-existing capital stock. But the pace of investment has declined, recently contracting. When companies don’t significantly invest, economic growth can’t accelerate.

Evans also noted that his business contacts stated the current pace of investment was about in-line with overall global demand, which naturally leads to the third causation for secular stagnation: weak demand. This is simply another way of saying weak growth. If the U.S. economy was growing 3% or more, we’d likely see an increase in investment. But businesses don’t need to increase their current pace of investment with US growth fluctuating around 2%.

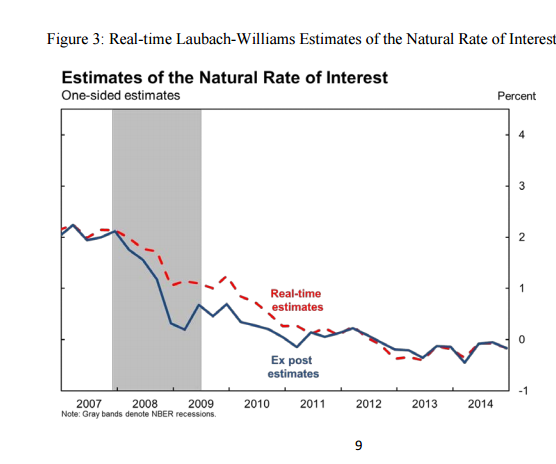

Finally, Evans turned to the natural rate of interest, arguing that the current low rate of this metric further bolsters Summers’ argument. Evans first notes that this idea is not new; Fed Chair Greenspan theorized its existence when he noted his “conundrum” while Ben Bernanke advanced the idea as part of his “global savings glut” theory. The San Francisco Fed has recently performed research on this topic and found that the US’ natural rate of interest is fluctuating around "0":

Evans noted anecdotal support for this theory:

‘I have also heard complementary reports from those on the other side of the market. In particular, issuers of high-quality corporate debt are finding markets receptive to their offerings, and new issues are routinely being oversubscribed.”

While some of this is undoubtedly people reaching for yield in a low-rate environment, there is also the fact that the natural rate of interest is simply far lower.

Summers' theory is growing less controversial. And with a Fed governor publicly expounding on the idea, the theory is likely to enter the mainstream of economic thought.