A few weeks ago, there was still a reasonable debate about whether US inflation would soon begin to peak. Whatever the merits of the argument, it’s been obliterated by the economic blowback from the war in Ukraine.

The central bank is now facing stark choices on monetary policy that can only be described as choosing from the lesser of bad options as a perfect storm of macro conditions triggered by the Ukraine war spreads across the globe.

Some of the Fed’s predicament is tied to leaving monetary policy too loose for too long and assuming that the recent rise in inflation would be “transitory.” There are signs that the supply-chain disruption is easing, which was/remains responsible for a significant chunk of the sharp increase in pricing pressure to date. As recently as mid-February that narrative had traction. But it’s mostly a moot point now as a war-related energy shock drives up inflation.

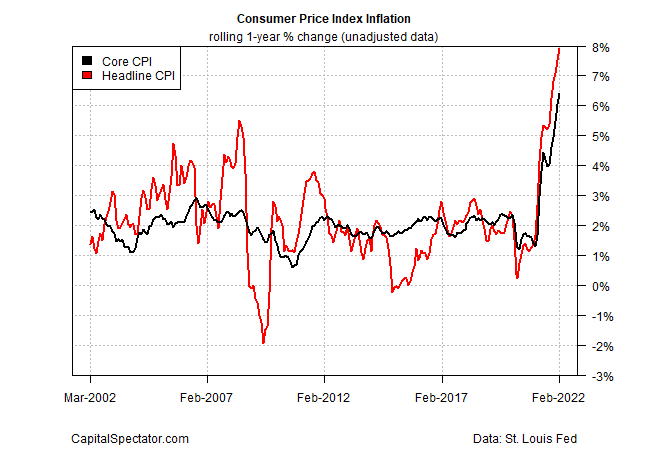

Yesterday’s news that US consumer inflation continued to increase in February is especially worrisome because the ongoing acceleration does not yet reflect Ukraine effect. Headline CPI rose 7.9% on a year-over-year basis through last month, a new 40-year high.

The challenge for Fed policy is easily summarized by comparing current interest rates to inflation. Even before the Ukraine shock fully is fully absorbed into prices the Fed is far behind the curve with a 0%-to-0.25% target rate. Using core CPI for reference, the Fed funds rate is roughly 6 percentage points below inflation. That’s a dramatic undershoot, and one that’s almost certain to widen in the near term as the Ukraine-related supply shock ripples through the global economy.

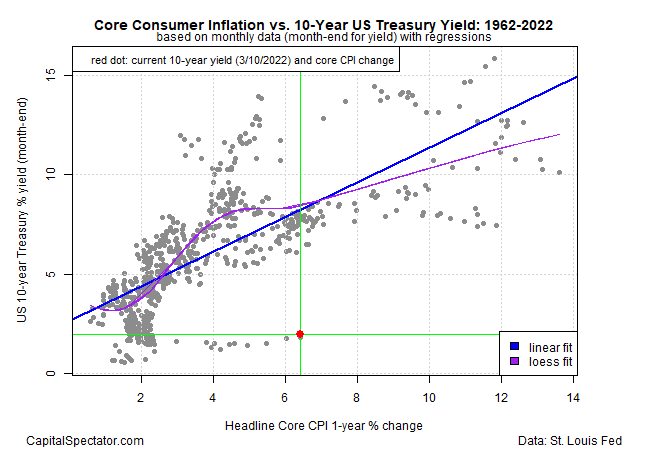

Notably, the Treasury market is heading into this new world order with current yields that don’t reflect the rapidly shifting ground of inflation. As a quick look at the state of the disconnect, consider how the current 10-year Treasury yield – 1.98% as of Mar. 10 – compares with history vis-à-vis core consumer inflation.

Using the 60-year relationship for core-CPI and the 10-year rate suggests that the Treasury market is dramatically underpricing inflation. There are several ways to interpret this, starting with the view that the market will be under strong pressure to raise yields (i.e., cut bond prices sharply).

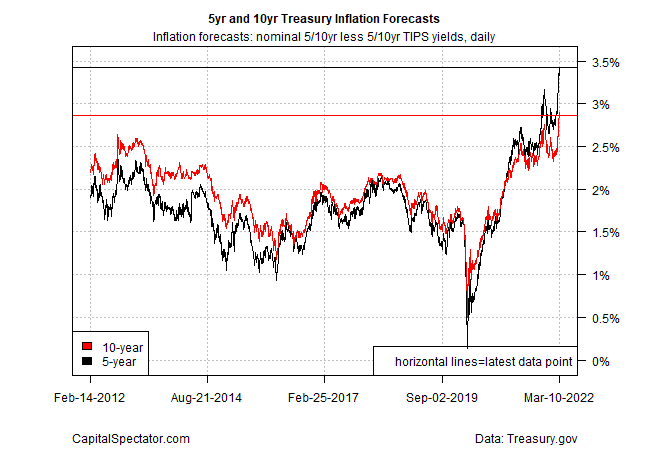

An alternative view is that the market is still pricing in a forecast that the inflation surge will ease at some point in the near future. Although there’s still a case for this analysis, it’s relevant only if your time frame is extended further out (relative to whatever the assumption was a few weeks ago). In the long run, the forces that have created a strong disinflation trend will resume. But for the foreseeable future, those forces are on hold (if not full-scale retreat) vis-à-vis war-related inflation pressure. Indeed, the Treasury market’s implied inflation forecasts are in the process of being revised up again, sharply, as the next chart below shows.

Deciding when the forces of disinflation will become dominant again has become unusually challenging since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Several major macro forces are now under severe stress, including globalization and energy supply. The uncertainty of war makes forecasting the return of something approximating “normal” macro conditions highly unclear at the moment. Accordingly, markets will likely require a bigger discount for this surge in uncertainty – i.e., higher yields in the Treasury market.

In fact, there are several facets to the uncertainty. On one hand, there’s a strong case for tighter Fed policy to deal with surging inflation. But the shockwave of higher energy prices raises the risk that economic growth will slow, perhaps sharply to the point of tipping the economy into recession. On that basis, the Fed may decide to slow and/or delay rate hikes.

Adjusting the calculus of what’s likely and what’s not will, until further notice, be a game of reassessing risk factors hour by hour and day by day as the Ukraine war unfolds. Since no one knows how the conflict will evolve, or how the global repercussions will manifest, adjusting Fed policy has rarely been more difficult or prone to error. It may be too extreme that the central bank is flying blind, but as relevant metaphors go that’s pretty close.

The risk of a policy mistake, in sum, is high. Unfortunately, so are the economic stakes, perhaps for years to come.