What are the implications for the U.S. dollar and investors’ portfolios if bond prices continue to fall, as they have of late? Within that context, should investors care whether the U.S. retains its status as a “reserve currency”? Should it effect the way investors think about their own cash reserves?

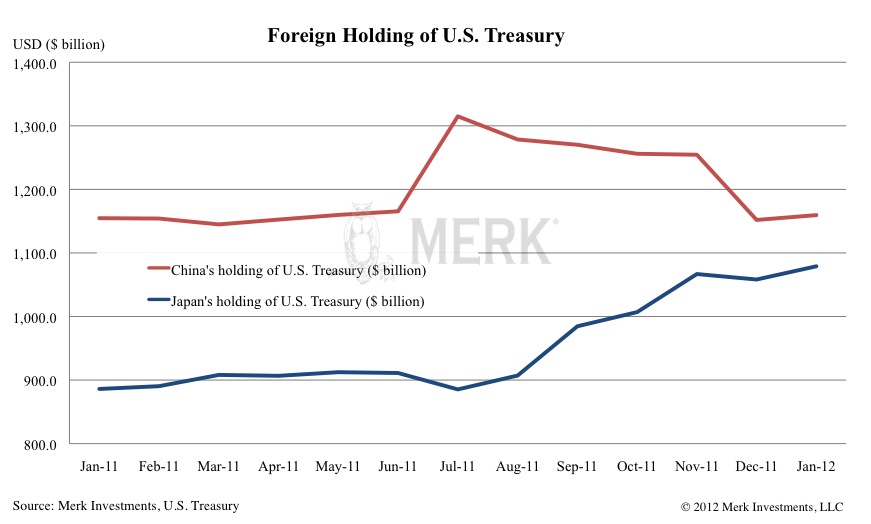

Until the end of last year, China had been a net seller of U.S. Treasuries for six consecutive months, spooking some investors that China might start to diversify its reserves in earnest. That trend was reversed in January, when its Treasury holdings grew by 0.7% in one month to $1.159 trillion; year-on-year, China’s holdings increased a mere $4.8 billion.

China’s year-on-year increase in Treasury holdings is sufficient to finance the U.S. current account deficit for about 3 business days; that’s a good reason why investors should care, as the current account deficit reflects the amount of U.S. dollar denominated assets foreigners need to buy just to keep the greenback from falling.

Whereas China has taken a breather with regard to piling on U.S. debt, Japan has increased its purchases of Treasuries, possibly because it is eager to weaken its own currency. Japan’s Treasury holdings now stand at $1.1 trillion. Together, total foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries rose 0.9% to a record $5.05 trillion in January.

Unfortunately, foreigners might be attracted to the U.S. dollar more for liquidity and less so for quality considerations. Central banks with billions to deploy are able to do so in U.S. Treasury markets without influencing market prices too much.

Think of it as the upside of issuing a huge amount of debt: there’s lots of it one can buy and sell. Liquidity, however, doesn’t guarantee success, as the Italian bond market has clearly shown; when weaker Eurozone countries are engulfed in a crisis of confidence, Italian bonds have often been sold as a proxy due to the size and depth of the market. Japan represents another large bond market. Still, the U.S. bond market dwarfs all of these. When it comes to perceived safe havens, Swiss government bonds may be hard to come by at times; given the erratic actions of the Swiss National Bank in recent months and years, we have to caution that even Switzerland may not be the safe haven some perceive it to be. Moving to Germany – considered to be a large, mature market by many – note that even German Treasury bills have been extremely difficult to obtain during stretches of the financial crisis, even at negative yields.

Indeed, one of the most positive global developments would be if emerging market countries develop their domestic fixed income markets. If governments, particularly in Asia, were to issue more debt in their domestic currencies, they would be less dependent on U.S. dollar funding, reducing the so-called contagion risk in a financial crisis.

Ideally, emerging markets would further develop both long-term bond markets, as well as short-term Treasury markets. The following example illustrates how global markets are so interrelated, and why such a development is so important: currently, a great deal of emerging market financing is U.S. dollar denominated, but originates from European banks. Those European banks, with trouble at home, are cutting their credit lines, to both shrink their loan portfolios, but also as their cost of borrowing U.S. dollars soared.

That’s because European banks historically obtain much of their U.S. dollar financing through U.S. money market funds. On average, U.S. prime money market funds held about 50% of their assets in U.S. dollar denominated commercial paper issued by European banks. After lots of public scrutiny, including from us, those holdings fell to about 1/3rd of money market fund assets in late 2011.

As U.S. money market funds reduced their appetite for debt issued by European banks, the Federal Reserve (Fed), in conjunction with other major central banks, put in place “central bank liquidity swaps”, a fancy way of describing U.S. dollar loans extended by the Fed to the European banking system via the European Central Bank (ECB) to alleviate U.S. dollar financing concerns and ultimately, contagion risks to the global economy.

A key attribute of liquidity is the ability to take money out of a country. An investor will be more willing to invest in a country when there are no capital controls, when there’s confidence in the rule of law, confidence that investors’ rights are protected. And while emerging markets are generally on the right path, it’s a path that takes a long time to build, as investors’ trust must be earned over many years.

As such, odds are the reserve currency status of the U.S. is likely to erode over time rather than overnight, if for no other reason than the lack of suitable alternatives. In our view, however, U.S. policy makers would be well served if they attempted to make the U.S. dollar as attractive as possible, rather than relying on the fact that foreigners have limited alternatives. As recent years have shown, the Chinese, for example, have gained operational experience in deploying their reserves into assets outside of U.S. Treasuries, in real assets, throughout the world: notably by investing in natural resources in Australia, Africa, Latin America and Canada.

For many years, until a month ago, the ECB, in its monthly communiqué, warned of a “potential for a disorderly correction of global imbalances.” That was central bank parlance for a dollar crash. For what it’s worth, the warning was missing for the first time in years in this month’s statement.[1] Like the boy who cried wolf, when someone warns about something repeatedly, few may take that risk seriously anymore. Is it complacency when one drops the warning?

What many don’t realize is that we don’t need a low probability / high-risk event – a “black swan” event – to be concerned. Take the recent turmoil in the Treasury market: from the high on February 28, 2012 until the close on March 15, 2012, the U.S. 30 year bond had fallen about 8.5% in value (with declines continuing as of this writing). Many have previously been chasing yields: a lot of money had moved into longer dated securities, the so-called long end of the yield curve.

In that process, volatility in that market had come down, providing the illusion of safety. We don’t need a crash, we need a return to a more normal environment to have what may be a rude awakening for investors. The plunge in the 30-year bond in just over 2 weeks should serve as a wake-up call. It turns out that foreigners appear to have piled into longer-dated Treasuries just before the recent correction (net long-term TIC flows of $101 billion in January vs. $38.5 billion expected), possibly making for a few very unhappy, but very important investors.

What is the relevance for the dollar? Foreign investors tend to own a large amount of Treasuries. When Treasuries fall in value, their investments may go down, unless the dollar increases by the same amount.

While some pundits – in an effort to comment on short-term currency moves on any one day - point out that falling bond prices make the dollar more attractive as yields are higher, that’s little consolidation to those already holding Treasuries. Indeed, historically speaking, our analysis indicates that the U.S. dollar tends to weaken during early and mid phases of an increasing interest rate cycle. That’s precisely because the bond market turns into a bear market in such an environment. It’s in the late phases of a tightening cycle that foreigners come back to the bond market, in anticipation that the next bull market for bonds is around the corner; in that phase, the dollar may get a reprieve.

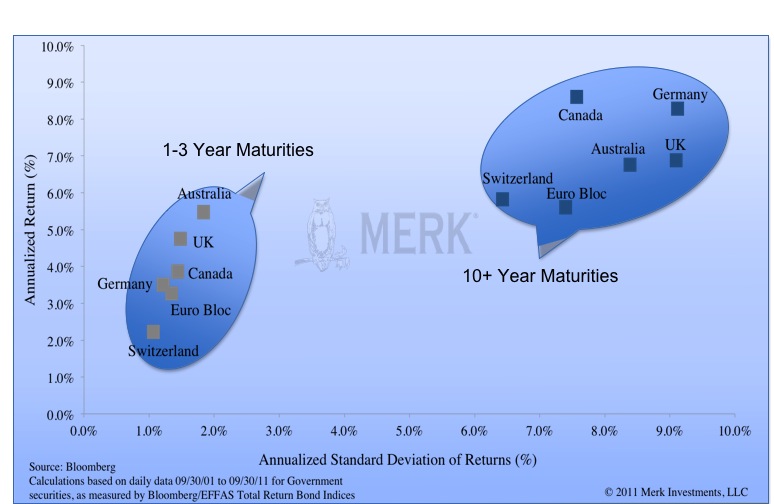

However, when rates are rising, investors may want to consider reducing their interest risk, moving from longer dated bond funds to shorter dated ones. Looking at it from an international perspective, the same relationship applies; it should not be a surprise that the volatility in shorter dated fixed income securities is less than that of longer dated ones:

Performance data in the chart above represents past performance and is no guarantee of future results.

For investors concerned about plunging bond prices, the obvious move may be to trim interest risk. Some may appreciate the perceived safety of U.S. dollar cash, although, as our discussion of U.S. money market funds above has shown, not all cash is equal.

Investors concerned about the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar may want to consider mitigating the potential risk of a declining dollar by diversifying to other currencies. Be warned, though, that currency risk is then introduced.

A money market fund will thrive to hold a stable net asset value in U.S. dollar terms; a currency fund will not. Indeed, much of investing is about trying to preserve purchasing power. By moving to cash in other currencies, one does avoid equity risk, and possibly mitigates interest and credit risk. But risk-free it is not. Indeed, we have argued for a long time that central banks may be eroding the purchasing power of currencies around the world – risk free assets can no longer be thought of as such. It was in 2006 when I first said “there is no such thing anymore as a safe asset: investors may want to consider a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Former ECB President Willem Duisenberg mentioned "risks pertaining to external imbalances" in the first time in March 1999. But he didn't reference it again until 2002. (Instead, he mentioned "there are no major imbalances in the euro area which would require a longer-term adjustment process" in 2001.) In May 2002, Duisenberg brought up this topic again at the press conference, saying "there are still a number of uncertainties such as those related to ... and to the impact of existing imbalances elsewhere on the world economy". He used the similar phrasing in June, October and December 2002 but not every meeting.

It was January 2003 that for the first time Duisenberg referenced "a disorderly adjustment of global imbalances" by saying "there are still risks relating to a disorderly adjustment of the past accumulation of macroeconomic imbalances, especially outside the euro area." Then he reiterated it a couple of times during his remaining term as ECB president ended in October 2003. A note here, current Greek PM and then ECB vice-president Lucas Papademos hosted the September conference in 2003, where he also referenced "macroeconomic imbalances in some regions of the world persist."

Since Trichet took office in November 2003, it became almost a routine to reference "external/global imbalances" at the press conferences, though his wording changed over time. During November 2003 and June 2006, Trichet often used the word "persistent global imbalances" when talking about concerns and risks to growth. Then he referenced "a disorderly unwinding of global imbalances" for the first time in August 2006. He frequently used "possible disorderly developments owing to global imbalances" during 2007-2008 and "adverse developments in the world economy stemming from a disorderly correction of global imbalances" in 2009, and started to regularly reference "concerns remain relating to … and the possibility of a disorderly correction of global imbalances" since September 2009, through his last press conference in October 2011. During his eight years in office, the only times he didn't mention "global imbalance" at all were August 2007, April 2005, and from October 2004 to January 2005.

Draghi continued the tradition of referencing "the possibility of a disorderly correction of global imbalances" in all of his press conferences from November 2011 to February this year. The past meeting in March was the first time he didn't reference it.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Falling Treasuries: A Currency Perspective

Published 03/21/2012, 12:57 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

Falling Treasuries: A Currency Perspective

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.