This is a post in three sections. First I want to outline my conception of the price level phenomena inflation and deflation. Second, I want to outline my conception of the specific inflationary case of hyperinflation. And third, I want to consider the predictive implications of this.

Inflation & Deflation

What is inflation? There is a vast debate on the matter. Neoclassicists and Keynesians tend to define inflation as a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.

Prices are reached by voluntary agreement between individuals engaged in exchange. Every transaction is unique, because the circumstance of each transaction is unique. Humans choose to engage in exchange based on the desire to fulfil their own subjective needs and wants. Each individual’s supply of, and demand for goods is different, and continuously changing based on their continuously varying circumstances. This means that the measured phenomena of price level changes are ripples on the pond of human needs and wants. Nonetheless price levels convey extremely significant information — the level at which individuals are prepared to exchange the goods in question. When price levels change, it conveys that the underlying economic fundamentals encoded in human action have changed.

Economists today generally measure inflation in terms of price indices, consisting of the measured price of levels of various goods throughout the economy. Price indices are useful, but as I have demonstrated before they can often leave out important avenues like housing or equities. Any price index that does not take into account prices across the entire economy is not representing the fuller price structure.

Austrians tend to define inflation as any growth in the money supply. This is a useful measure too, but money supply growth tells us about money supply growth; it does not relate that growth in money supply to underlying productivity (or indeed to price level, which is what price indices purport and often fail to do). Each transaction is two-way, meaning that two goods are exchanged. Money is merely one of two goods involved in a transaction. If the money supply increases, but the level of productivity (and thus, supply) increases faster than the money supply, this would place a downward pressure on prices. This effect is visible in many sectors today — for instance in housing where a glut in supply has kept prices lower than their pre-2008 peak, even in spite of huge money supply growth.

So my definition of inflation is a little different to current schools. I define inflation (and deflation) as growth (or shrinkage) in the money supply disproportionate to the economy’s productivity. If money grows faster than productivity, there is inflation. If productivity grows faster than money there is deflation. If money shrinks faster than productivity, there is deflation. If productivity shrinks faster than money, there is inflation.

This is given by the following equation where R is relative inflation, ΔQ is change in productivity, and ΔM is change in the money supply:

R= ΔM-ΔQ

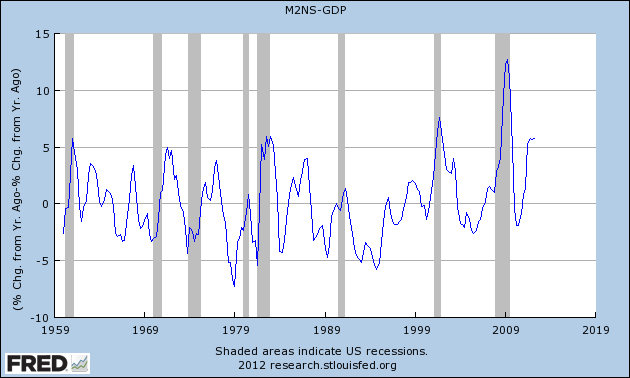

This chart shows relative inflation over the past fifty years. I am using M2 to denote the money supply, and GDP to denote productivity (GDP and M2 are imperfect estimations of both the true money supply, and the true level of productivity. It is possible to use MZM for the money supply and industrial output for productivity to produce different estimates of the true level of relative inflation):

Inflation and deflation are in my view a multivariate phenomenon with four variables: supply and demand for money, and supply and demand for other goods. This is an important distinction, because it means that I am rejecting Milton Friedman’s definition that inflation is always and only a monetary phenomenon.

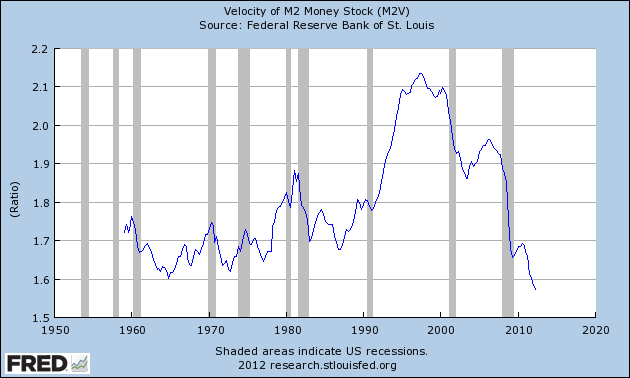

Friedman’s definition is based on Irving Fisher’s equation MV=PQ where M is the money supply, P is the price level, Q is the level of production and V is the velocity of money. To me, this is a tenuous relationship, because V is not directly observed but instead inferred from the other three variables. Yet to Friedman, this equation stipulates that changes in the money supply will necessarily lead to changes in the price level, because Friedman assumes the relative stability of velocity and of productivity. Yet the instability of the money velocity in recent years demonstrates empirically that velocity is not a stable figure:

And additionally, changes in the money supply can lead to changes in productivity — and that is true even under a gold or silver standard where a new discovery of gold can lead to a mining-driven boom. MV=PQ is a four-variable equation, and using a four-variable equation to establish causal linear relationships between two variables is tenuous at best.

Through the multivariate lens of relative inflation, we can grasp the underlying dynamics of hyperinflation more fully.

Hyperinflation

I define hyperinflation as an increase in relative inflation of above 50% month-on-month. This can theoretically arise from either a dramatic fall in ΔQ or a dramatic rise in ΔM.

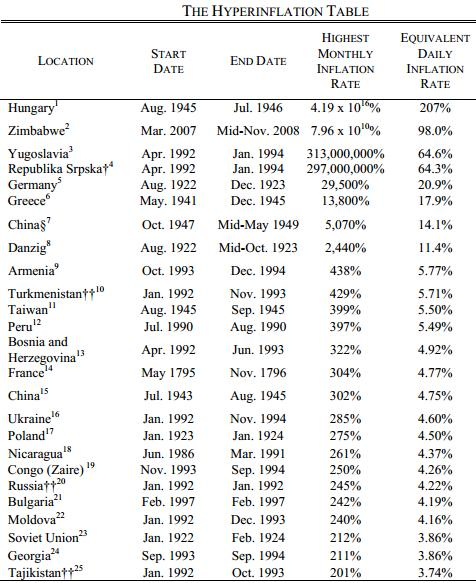

There are zero cases of gold-denominated hyperinflation in history; gold is naturally scarce. Yet there have been plenty of cases of fiat-denominated hyperinflation:

This disparity between naturally-scarce gold which has never been hyperinflated and artificially-scarce fiat currencies which have been hyperinflated multiple times suggests very strongly that the hyperinflation is a function of governments running printing presses. Of course, no government is in the business of intentionally destroying its own credibility. So why would a government end up running the printing presses (ΔM) to oblivion?

Well, the majority of these hyperinflationary episodes were associated with the end of World War II or the breakup of the Soviet Union. Every single case in the list was a time of severe physical shocks, where countries were not producing enough food, or where manufacturing and energy generation were shut down out of political and social turmoil, or where countries were denied access to import markets as in the present Iranian hyperinflation. Increases in money supply occurred without a corresponding increase in productivity — leading to astronomical relative inflation as productivity fell off a cliff, and the money supply simultaneously soared.

Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus of the Cato Institute note:

Hyperinflation is an economic malady that arises under extreme conditions: war, political mismanagement, and the transition from a command to market-based economy—to name a few.

So in many cases, the reason may be political expediency. It may seem easier to pay workers, and lenders, and clients of the welfare state in heavily devalued currency than it would be to default on such liabilities — as was the case in the Weimar Republic. Declining to engage in money printing does not make the underlying problems — like a collapse of agriculture, or the loss of a war, or a natural disaster — disappear, so avoiding hyperinflation may be no panacea. Money printing may be a last roll of the dice, the last failed attempt at stabilising a fundamentally rotten situation.

The fact that naturally scarce currencies like gold do not hyperinflate — even in times of extreme economic stress — suggests that the underlying mechanism here is of an extreme exogenous event causing a severe drop in productivity. Governments then run the printing presses attempting to smooth over such problems — for instance in the Weimar Republic when workers in the occupied Ruhr region went on a general strike and the Weimar government continued to print money in order to pay them. While hyperinflation can in theory arise either out of either ΔQ or ΔM, government has no reason to inject a hyper-inflationary volume of money into an economy that still has access to global exports, that still produces sufficient levels of energy and agriculture to support its population, and that still has a functional infrastructure.

This means that the indicators for imminent hyperinflation are not economic so much as they are geopolitical — wars, trade breakdowns, energy crises, socio-political collapse, collapse in production, collapse in agriculture. While all such catastrophes have preexisting economic causes, a bad economic situation will not deteriorate into full-collapse and hyperinflation without a severe intervening physical breakdown.

Predicting Hyperinflation

Hyperinflation is notoriously difficult to predict, because physical breakdowns like an invasion, or the breakup of a currency union, or a trade breakdown are political in nature, and human action is anything but timely or predictable.

However, it is possible to provide a list of factors which can make a nation or community fragile to unexpected collapses in productivity:

- Rising Public and-or Private Debt — risks currency crisis, especially if denominated in foreign currency.

- Import Dependency — supplies can be cut off, leading to bottlenecks and shortages.

- Energy Dependency — supplies can be cut off, leading to transport and power issues.

- Fragile Transport Infrastructure — transport can be disrupted by war, terrorism, shortages or natural disasters.

- Overstretched Military — high cost, harder to respond to unexpected disasters.

- Natural Disaster-Prone — e.g. volcanoes, hurricanes, tornadoes, drought, floods.

- Civil Disorder— may cause severe civil and economic disruption.

Readers are free to speculate as to which nation is currently most fragile to hyperinflation.

However none of these factors alone or together — however severe — are guaranteed to precipitate a shock that leads to the collapse of production or imports.

But if an incident or series of incidents leads to a severe and prolonged drop in productivity, and so long as government accelerates the printing of money to paper over the cracks, hyperinflation is a mathematical inevitability.