On the campaign trail, Donald Trump’s supporters seemed to be of two positions when it came to trade policy: there were those that took every word and fervently believed the candidate when he said "Buy American" would "Make America Great Again". Then there were those among the supporters who saw the risk of taking that policy too far, but still felt comfortable in the belief that come the day the candidate reached the Oval Office a more conciliatory, if still robustly pro-U.S. line would be pursued.

Well, if further clarification was needed it was made clear in the new president’s inauguration pledge to buy American and hire American, followed by one of his first executive orders to strike-out the Trans-Pacific Partnership after seven years of painstaking negotiation.

In itself, the pledge to buy American and hire American is admirable, commendable and logical. The risk comes when it is enforced by the application of arbitrarily applied tariff barriers. History is littered with examples of previous leaders who have sought to protect domestic jobs and industries by putting up tariff barriers. As recently as 2002, George W. Bush slapped tariffs on steel imports instigating a wave of World Trade Organization complaints and, a year late,r a ruling from the WTO that the steel tariffs were illegal.

Whither the WTO?

Eventually Bush backed down and order was restored, but only because all sides accepted the legitimacy of working within a rules-based system such as the WTO. As a recent article in the Telegraph observed, the international community built the current system after the devastation of World War II and the Great Depression precisely hoping the we could avoid the self-inflicted wounds resulting from tit-for-tat trade disputes.

The US was central in that process and helped craft the rules in its own image of fair and open terms of trade. The fact is that other countries don’t stand still if a trading partner arbitrarily applies a tariff, quota or import tax. The idea of rules-based system such as the WTO is that these disputes can be resolved within a framework that, however tortuous, is accepted by all parties as balanced, but we should take note of the new President’s statements. He generally means what he says.

So, when Trump vowed to “renegotiate” America’s relationship with the WTO if it tries to block his protectionist policies, adding “we’re going to renegotiate or we’re going to pull out,” (something he said last year), declaring “these trade deals are a disaster. The WTO is a disaster,” he is clearly signalling he has no intention of letting the internationally accepted WTO system get in the way of his ideas for putting up barriers to imports.

What Has NAFTA Brought the US?

The consequences of such action should not be underestimated. Over the last 20 years the creation of NAFTA and the consequences of lower transport costs and better communications has meant U.S. corporations large and small have become more integrated with suppliers overseas, both with their own operations and third parties.

Source: Telegraph Newspaper

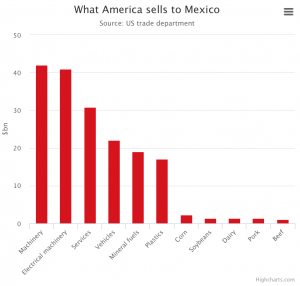

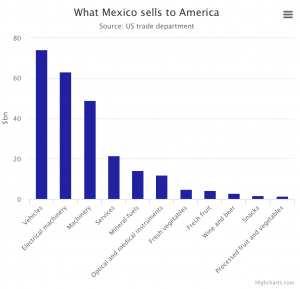

Many U.S. corporations are extensively integrated with the Mexican manufacturing sector and, therefore, exposed to any changes.

Source: Telegraph Newspaper

A radical shakeup of the tariff system would have a profound impact on the price of just about every industrial and consumer good sold in the U.S. U.S. Foreign direct investment in China, for example, stands at $65.8 billion, whereas China’s in the U.S. is only $9.5 billion, meaning the U.S. is far more reliant on open access to China than the other way around. The Telegraph points out China could easily buy Airbus over Boeing. Or Brazilian soy over U.S. soy. Or put the squeeze on Apple’s supply chain in China. Sure, iPhones could, in time, be made wholly in the U.S.A. but consumers are going to have to pay a lot more for them.

If the intention is to boost domestic jobs by putting up barriers, then the risk is if companies like Apple move to reshore production they would seek to automate in order to avoid the higher U.S. labor cost. Automation is already a growing challenge to job creation in mature markets, forcing firms to relocate would also force the pace of automation.

Tariff barriers are like using a hammer to crack a nut. However attractive the grand gesture of slapping up barriers may seem, a more subtle approach to encouraging firms to buy American and, where possible, to relocate production would be much more beneficial for the U.S. economy. President Trump’s other idea of re-writing the U.S. tax system would be a good place to start.