We know that the narrowing of spreads in the eurozone is largely due to the European Central Bank and notably to the announcement, by ECB president Draghi, of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). Yet the improvement is also due to the spectacular adjustment of external accounts carried out by most of the so-called peripheral countries, namely Spain, Portugal Ireland and Italy.

As persistent balance of payment imbalances pose a problem in a monetary union that is not a transfer union, the actual convergence of current account balances within the eurozone signals a steady but fundamental decline in the risk of a breakup.

The correction of current account deficits is due in part to fiscal consolidation. The impact is both direct -- by reducing its financing needs, the government reduces those of the economy as a whole – and indirect – higher fiscal pressure is accompanied by an increase in the household savings rate, notably during periods of recession. As to companies, faced with weaker prospects for demand and a restricted credit supply, they tend to cut back investment. In other words, fiscal belt-tightening triggers a drop-off in domestic demand, and thus imports.

Yet an analysis of the trade balances of the southern European countries shows that to a large extent, the external adjustment is due to increasing exports. Between October 2011 and October 2012, the aggregate trade deficit of Spain and Portugal contracted by €15.7bn, of which €9.6bn can be attributed to export growth.

The only exception is Greece, where the depth of the recession is unrivalled. Numerous corporate bankruptcies have considerably reduced Greece’s export base. The trade deficit has contracted by €5.8bn in a year, but merchandise sales abroad increased by only €1.2bn.

The turnaround in external accounts is largely the fruit of the peripheral countries’ efforts to regain competitiveness. On average, unit labour costs in southern Europe at year-end 2012 were estimated to be 9% lower than the 2008 level. In addition to the internal devaluation derived from austerity and higher unemployment, reforms of the job market and the markets for goods and services also benefited exports.

Compared to precrisis peak levels, real exports are now 11.7% higher in Spain, 7.1% higher in Ireland and 5.3% higher in Portugal. This is a structural improvement and part of a vaster movement to reallocate production resources from protected activities (such as real estate) towards export sectors.

These performances are all the more remarkable considering they occur in the midst of recession in the eurozone, the main export market of the southern European countries. Their companies have won market share within the EMU, which not only offset somewhat the decline in demand addressed to these countries, but more importantly, reduces intra-zone current account imbalances. With the gradual restoration of private capital mobility, Target 2 positions have begun to reduce. The announcement of OMT played a key role in getting portfolio investment to return to the peripheral debt segments.

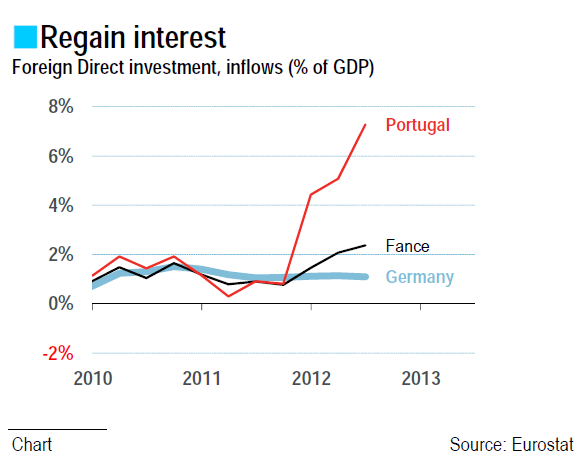

Major gains in competitiveness in these countries have also played a role in the return of foreign direct investment (FDI). In Portugal, inflows have reached nearly 8% of GDP, the highest level on record. These inflows are important: they not only provide a stable source of financing of foreign deficits, but often create jobs and promote innovation as well. For the southern European countries specialised in the production of low value-added goods, these investments are essential for moving upmarket and for consolidating competitiveness gains.

The adjustment of current account balances is an essential step in resolving the eurozone debt crisis. It mirrors the debt reduction efforts of the peripheral countries but also the narrowing of the competitiveness gap, both of which are preconditions for the greater mutualisation of risks within the eurozone.

By Thibault MERCIER

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Eurozone Spreads: Narrowing The Gaps

Published 01/21/2013, 04:44 AM

Updated 03/09/2019, 08:30 AM

Eurozone Spreads: Narrowing The Gaps

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.