Landfall of a “Told You So” Moment…

Late last year and early this year, we wrote extensively about the problems we thought were coming down the pike for European banks. Very little attention was paid to the topic at the time, but we felt it was a typical example of a “gray swan” – a problem everybody knows about on some level, but naively thinks won’t erupt if only it is studiously ignored. This actually worked for a while, but as Clouseau would say: “Not anymeure!”

Readers may want to check these previous missives out, which provide a lot of background information and color (in chronological order: “Insolvent Zombies”, “Drowning in Bad Loans” and “The Walking Dead: Something is Rotten in the Banking System”). What is happening now is therefore a “told you so” moment, because, well… we told you so.

Following the “Brexit” vote, market participants have begun to focus their attention on what we thought they would focus it on: namely on the risks posed by continental Europe. Perversely, the mainstream press on the continent is brim-full with lamentations describing in lurid prose what an unmitigated catastrophe leaving the EU will be for the United Kingdom! (as we promised, we will write about this in more detail soon – it is truly funny to watch). In reality, the UK has left what increasingly looks like a sinking ship.

One bank that did get its share of unwelcome media attention was Europe’s biggest zombie, Deutsche Bank (NYSE:DB). Its share price has continued to tumble relentlessly, for no immediately obvious reasons. In a way this is faintly reminiscent of Creditanstalt in 1931 – in the sense that Deutsche’s position in the European banking system of today is of roughly similar importance as Creditanstalt’s was back then. This is mainly due to its extremely large derivatives positions, which make it a lynchpin in a vast web of contractual obligations – it is so to speak the mother of all counterparties.

We would however argue that while this is indeed a bit worrisome, the real danger clearly comes from elsewhere. Deutsche Bank is, after all, headquartered in Germany, and its domestic market is strong. In fact, the real danger is still right where it always was: in Italy and Spain – and to a slightly lesser extent in Greece as well.

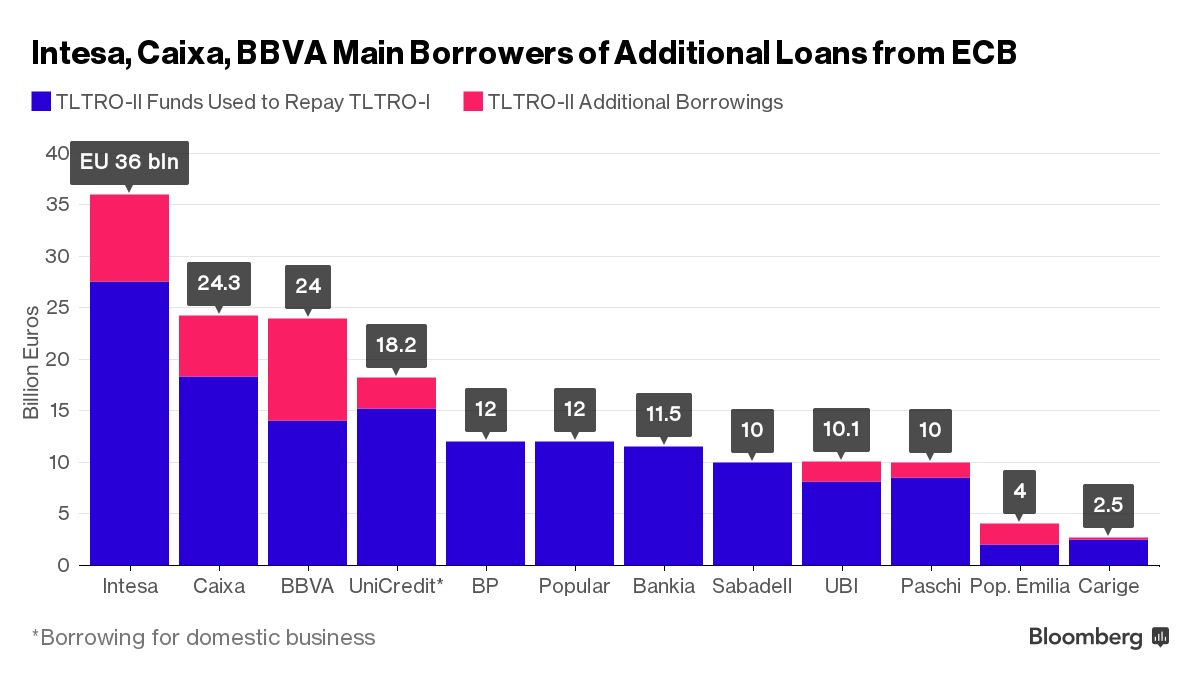

Italian banks are sitting on €360 billion in non-performing loans – including, so we are told, loans of the “extend and pretend” variety. Just one day after the Brexit vote, the ECB’s TLTRO II operation took place. Almost €400 billion were lent to euro area banks at negative interest rates. The banks also paid the bulk of the less generous TLTRO I loans back, leaving net new TLTRO additions at about €31 billion. Most of the new TLTRO II loans were taken up – you guessed it – by Italian and Spanish banks (details here).

TLTRO -II: the ECB is subsidizing European banks by offering them fresh funds at negative interest rates, under the condition that they engage in the very thing that has produced the crisis in the first place: more credit expansion ex nihilo! The biggest borrowers are the very banks that are drowning in bad loans – click to enlarge.

Add to that approx. €25 billion or so in QE since the Brexit, and a €150 billion liquidity guarantee for Italian banks approved by the EU commission on June 30, and you would think that maybe there would at least be some short-covering in European bank stocks. Not so:

Here is a long term view of the EURO STOXX Banks index that shows both the boom and the bust – and also illustrates that the sector is now precariously poised at a last ditch support level.

A Legal Dance on Eggshells

As we have pointed out in our previous missives, the EU has at least tried to do something to prevent tax payers from having to involuntarily fund future bank bailouts. Instead, investors and depositors are supposed to shoulder some risk. Given that there is no way the EU will return to honest money and a free market in banking, this is a kind of “second-best solution”, i.e., it is better than nothing.

The problem is however that fractional reserve banking remains a fraudulent practice. Leaving aside the central bank backstop for a moment, let us consider a simple example: Anna pays 100,000 euro into her bank account, as a demand deposit. The next day, the bank creates a deposit of 90,000 euro in favor of Tony as a loan (we are assuming a 10% reserve requirement – in reality it is just 1% in euro-land!). Tony immediately pays the money into Richard’s current account, to pay for a rickety second-hand sailboat allegedly moored in Malta somewhere.

Now the account slip of Anna says: “You can have 100,000 euro on demand” (i.e., anytime). Richard’s account slip says “you can have 90,000 euro on demand”. Tony meanwhile owes the bank €90,000 – but he obviously doesn’t have the money at the moment. Neither does the bank have it. No one paid in 90,000 euro in additional deposits.

If Anna and Richard both come in to withdraw their €190,000, they will find that only €100,000 are actually there. So now two people apparently have a perfectly valid legal claim on the same money. The bank never told Anna “we’re going to lend your money out the next day, and actually, it’s not going to be available on demand, not really, anyway. Only under certain circumstances”. In other words, Anna’s money has been misappropriated. This, in short, is fraud. At least it is when anyone else but a bank does it.

So while the EU’s Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive (BRRD) at least restores some degree of normalcy by prohibiting willy-nilly bank bailouts, there is a bit of a problem when it comes to “bailing in” depositors – because their deposits are largely fictitious, something they are as a rule not even aware of.

Roman Jurist Ulpian, AD 170 – AD 223. In the Digest, a part of the Corpus Juris Civilis, he writes on bank insolvencies:

“…once a banker’s goods have been sold and the concerns of the privileged attended to, preference should be given people who, according to attested documents, deposited money in the bank. Nevertheless, those who have received interest from the bankers on money deposited will not be dealt with separately from the rest of the creditors; and with good reason, since to loan is one thing and to deposit is another.”

Ulpian is clearly establishing the legal difference between demand deposits and time deposits, resp. loans.

It is an edifice that stands on extremely wobbly legal ground, particularly in view of the fact that the practice of lending out demand deposits has been rightly deemed fraudulent in European legal tradition for most of the time from antiquity onward (there even exist 20th century court rulings upholding this view).

The Italian Problem

In Italy there are now several additional problems. The first one is that a great many “Tonys” have turned out to be deadbeats. As per the example above, the only way for both Anna and Richard to be made whole is if Tony pays back his loan, or if the bank pays the money out of its own equity. In the modern fiat money system, it can also obtain liquidity from the central bank. The problem is that this is tied to certain rules. Hence the “150 billion liquidity guarantee” that the Italian government has now been allowed to extend.

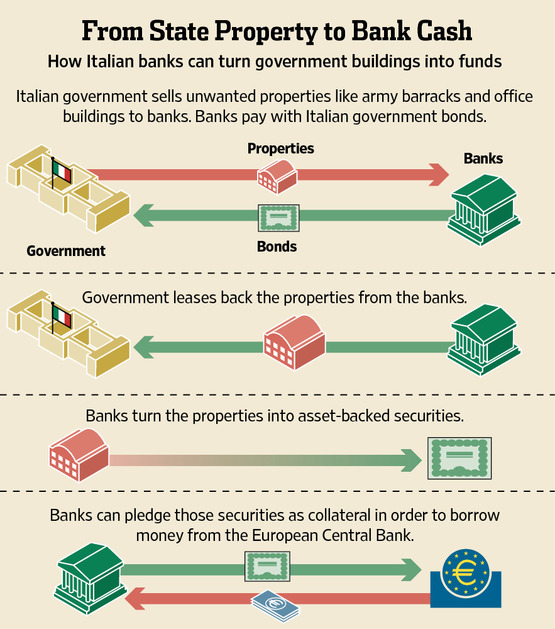

As we have mentioned on several occasions, the Italian government and Italy’s banks have been propping each other up in a bizarre three-card Monte ever since the euro area crisis began. It is almost as though Enron and Worldcom had been trying to avoid bankruptcy by propping each other up. The only difference – a decisive one to be sure – is that Italy has the ECB as a go-between, and the ECB can create money ex nihilo in unlimited amounts.

Here is a chart we have shown before, illustrating what they did in 2012 to create assets that could be pawned off to the ECB in its LTRO operations:

This deserves an “A” for creativity: how an insolvent government and insolvent banks can prop each other up – as long as there’s a go-between with a printing press.

Italy’s government has another problem though: many of the now de facto (though not de iure – yet) insolvent Italian banks have not only funded themselves with deposits, they have also sold wagon-loads of subordinated debt to widows and orphans.

The risks were surely mentioned in passing in the small print, but it is a good bet that a smart lawyer could show that many of the buyers were not exactly made fully aware of the risks they were exposed to. We would guess that truth in advertising was very low on the list of priorities when Italy’s banks urgently needed to prop up their capital to make it through one of the EU’s farcical stress test exercises.

Banca Monte dei Paschi (OTC:BMDPY), chart above, – since 2007, the share price of Italy’s 3rd largest bank has declined from €2,100 to €0.23 – it is fair to assume that it has a few problems. The biggest one is that it is basically bankrupt.

For Mr. Renzi, this means that he will likely face what has become known as a “populist backlash” if he applies the BRRD chapter and verse – because then, all those widows and orphans will lose their hard-earned money (actually, it is already lost – they just don’t know it yet). As knowledgeable friends assure us, this is actually the biggest danger from the EU’s perspective. The banks can always be kept above the water-line, as long as the ECB is willing to extend ELA (= emergency liquidity assistance).

If Beppe Grillo wins an election in Italy, the situation could become dicey though – and this could easily happen sooner rather than later. In October there is a constitutional referendum in Italy, called for by Mr. Renzi. The aim is to make Italian governments more stable by reducing the number of Senate seats from 315 to 100 and limiting the Senate’s ability to bring down governments. The thing is: Renzi has said he will step down if the reform attempt is rejected in the referendum, and that would mean new elections.

Waiting in the wings: Beppe Grillo, leader of the Five Star Movement. As Bloomberg reports:

“Meanwhile, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement is poised to profit from a defeat. An opinion poll by the Demos institute showed last week that Five Star has overtaken Renzi’s Democratic Party to become the country’s most popular group. Five Star wants to hold a referendum on Italian membership of the euro.”

(emphasis added)

In short, it is not only the banks and their creditors that are at risk – there is considerable political risk attached to the deteriorating situation in Italy’s banking system as well. Eventually, there could well be a political earthquake that will make the “Brexit” look like inconsequential foreplay.

Not surprisingly, Mr. Renzi is already threatening to ignore the BRRD if need be and bail out the banks anyway – something that has so far not exactly found favor in Brussels. We’ll see though what happens when push indeed comes to shove, which seems an increasingly likely prospect. Of course, as noted above, Italy’s government isn’t exactly a paragon of financial prudence itself (meaning, technically, it is bankrupt too).

Conclusion

If one ponders the situation in Europe as a whole, it seems that the efforts to solve the problems left in the wake of the last boom-bust cycle have in many cases involved a kind of multi-layered shell game. Unsound debt has often not really been liquidated – instead it has been shifted around, renamed, put on the back burner, etc. The most obvious case is the bailout of Greece, which is really hard to beat as far as ludicrous extend and pretend schemes go.

Nevertheless, generally European banks have actually done quite a lot to shore up their capital, write down impaired assets and make their balance sheets less risky – according to the officially accepted definition of risk, that is (as far as we are concerned, stuffing one’s balance sheet with government debt is actually not really a good way to make it less risky). A major reason for the weakness in bank stocks is that it has become difficult for the banks to make money – low interest rates, a negative deposit facility rate, stricter capital requirements and new bank taxes all weigh on their ability to make profits.

In some countries the banks are facing problems which are obviously a lot bigger though – and it seems they may actually be too big. For instance, once a borrower defaults in Italy, it reportedly takes between 7 to 8 years for the case to worm its way through the courts. This makes it highly uncertain what, if anything, can be recovered from defaulted loans. With the lingering problems in the banking system coming to a head, other problems that have been largely left simmering in the background may soon be coming to a head as well.

It appears to us that the main side-effect of the “Brexit” was to serve as a wake-up call, reminding everyone that the crisis in Europe is not over.