The Euro crisis is getting deeper into the uncharted territory with bond yields surging across Europe on Friday Nov. 25, after Fitch Ratings cut Portugal’s debt rating to “junk” status. Standard & Poor’s later also delivered a debt downgrade to Belgium to AA from AA+. Moody’s stayed busy and lowered Hungary’s debt rating to junk on Thursday. Meanwhile, Greece reportedly was trying to negotiate a bigger haircut with its creditors.

Elsewhere, Italy has a debt load of €1.9 trillion, or 120% of GDP, with €306 billion due to mature in 2012 alone. With its 2-year and 10-year sovereign bond yield spiking to a record 7%+, "too big to bail" would be an appropriate description of Italy right now.

Telegraph cited an analyst estimate that rescuing Italy would cost around €1.4 trillion, while the Euro Zone’s rescue fund has only €440 billion--a near €1 trillion shortfall. And the Financial Times reported that the European Financial Stability Facility may not be able to increase its capacity from the current €440 billion due to "worsening of market conditions over the past month."

Spain is definitely feeling the pain. Spanish I0-year government bond yield already got pushed up to close to 7%. Reuters reported that the new Spanish centre-right government is considering an application for international aid.

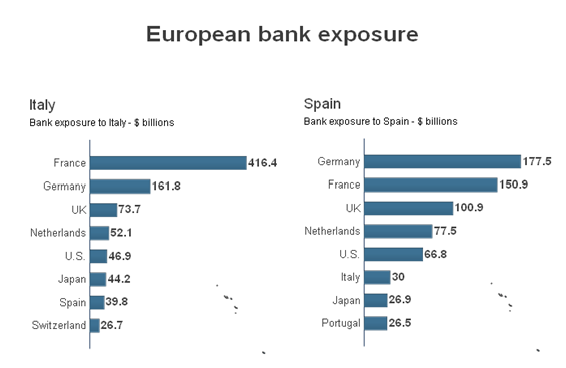

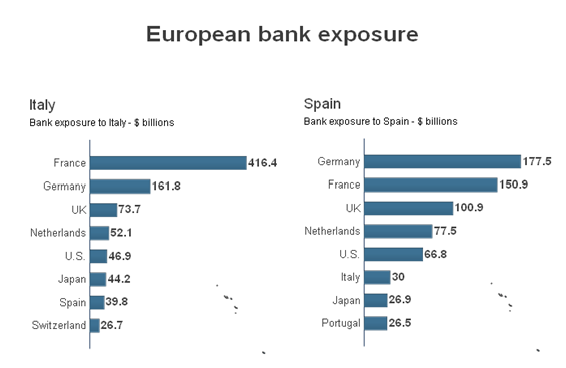

Markets are concerned about the potential exposure of European banks now that the borrowing cost of both Italy and Spain is hovering at the proverbial 7%, which was the level that sent Greece, Ireland and Portugal seeking bailout. German and French banks have the most exposure to Italy and Spain sovereign debt (see chart below).

The bond rout has spread into the other major Euro members while putting a strain on Europe's financial system as well. German debt has long been the safe haven, but even Germany could not find buyers for about 40% of its €6-billion 10-year bonds auction last week.

Meanwhile, both Fitch and Moody's warned of a possible downgrade of France AAA status due to the continuing intensification of Euro debt crisis. S&P did downgrade France, although an error now under investigation, it nevertheless suggests something in the works at S&P.

The two charts published at the Guardian from analysts show the unrelenting ascend of Euro Zone government 10-year and 2-year bond yields weighted by each country's GDP, which is a rough approximation of borrowing costs for the entire Euro Zone.

10-year Euro Zone Government Bond Yield Weighted by GDP

(Source: The Guardian, 23 Nov 2011)

2-year Euro Zone Government Bond Yield Weighted by GDP

(Source: The Guardian, 23 Nov 2011)

So far analysts and market players have formulated two possibilities to contain the situation:

Euro Zone sovereign debt pooled in the form of Euro bonds, which would put Germany on the line to implicitly guarantee the peripheral debt

The European Central Bank (ECB) as the lender of last resort by buying up massive quantities of sovereign bonds from indebted euro-zone members

Between the two, we see the Euro bond as the more likely option.

ECB's Euro Zone bond-buying spree of €195 billion since May 2010 has not been successful to contain the interest rate spike, and we doubt more purchases would restore market confidence that much. Moreover, concern over the potential inflationary effect is part of the reason behind German Chancellor Angela Merkel's opposition to ECB expanding its role in bond monetization.

There are market chatters of a potential dissolution or default of the Euro. But some economists believe that the outright collapse of the Euro could reduce GDP in its member-states by up to half and trigger mass unemployment, which could lead to widespread civil unrest and property losses. In that scenario, a recession/depression in Europe and the world would be closer to a probability of 100%.

On the other hand, Euro bond, with the guarantee of the stronger Euro countries, would leverage and facilitate the highly indebted weaker members to get financing at sustainable rates, to repay debt while maintaining some growth. That would in turn benefit other European countries, such as Germany, export business as well.

The failure of the last German bond auction is a reflection of markets losing confidence in the Euro rather than in Germany itself. Without the Germans backing up other troubled sovereign debt, Europe will be increasingly short on cash as investors flee the region. Eventually, Germany would not be immune to an ensuing catastrophic financial system meltdown.

But the Euro bond would only kick the can down the road, and Germany knows it. Germany is reluctant to grant guarantee or fund anything without the peripheral governments' commitment to get their debt and deficit under control. The highly indebted Euro members, on the other hand, are just as reluctant to commit to drastic austerity measures after years of spending way beyond their means. So this is basically the hold-up right now.

During the past 2+ years of this debt crisis in the Euro Zone, Germany, with its strong economy, has emerged as the leader wielding the most power. Euro bond will not achieve its intended purpose without the support of Germany. Europe's future now lies largely in the hands of the German.

Merkel has vehemently opposed the idea of Euro bond, but some within Merkel's governing coalition reportedly are no longer ruling out the introduction of euro bonds. From Spiegel,

"We never say never. We only say: No euro bonds under the existing conditions," Norbert Barthle, budgetary spokesperson for the conservatives in parliament, told the Financial Times Deutschland.

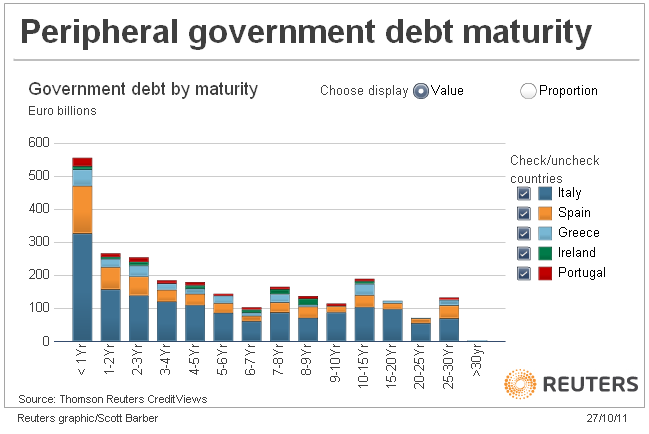

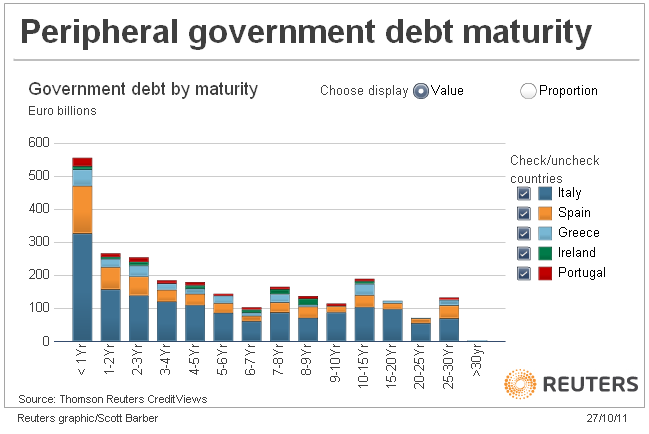

Spain and Italy have the lion's share of the peripheral government debt to mature over the next three years with 2012 being the most critical (See Chart Below)

Working within that timeline, even if busting up the Euro union were a viable option to entertain, the complexity involved with multiple currency conversions would preclude it as something that could be implemented within a year.

Italy, Spain, France and Belgium will each go to market this week to auction bonds worth billions of euros. The outcome of these auctions most likely would push up Euro bond discussion with the Europe decision makers.

Time is basically running out, eventually some compromise, for example, certain GIIPS club member(s) leaving the Union, has to be accomplished to break the current stalemate.

Swift decision making has not been one of Merkel's traits, but the consequence of inaction and delayed action could be much more disastrous for Europe and the world.

Elsewhere, Italy has a debt load of €1.9 trillion, or 120% of GDP, with €306 billion due to mature in 2012 alone. With its 2-year and 10-year sovereign bond yield spiking to a record 7%+, "too big to bail" would be an appropriate description of Italy right now.

Telegraph cited an analyst estimate that rescuing Italy would cost around €1.4 trillion, while the Euro Zone’s rescue fund has only €440 billion--a near €1 trillion shortfall. And the Financial Times reported that the European Financial Stability Facility may not be able to increase its capacity from the current €440 billion due to "worsening of market conditions over the past month."

Spain is definitely feeling the pain. Spanish I0-year government bond yield already got pushed up to close to 7%. Reuters reported that the new Spanish centre-right government is considering an application for international aid.

Markets are concerned about the potential exposure of European banks now that the borrowing cost of both Italy and Spain is hovering at the proverbial 7%, which was the level that sent Greece, Ireland and Portugal seeking bailout. German and French banks have the most exposure to Italy and Spain sovereign debt (see chart below).

The bond rout has spread into the other major Euro members while putting a strain on Europe's financial system as well. German debt has long been the safe haven, but even Germany could not find buyers for about 40% of its €6-billion 10-year bonds auction last week.

Meanwhile, both Fitch and Moody's warned of a possible downgrade of France AAA status due to the continuing intensification of Euro debt crisis. S&P did downgrade France, although an error now under investigation, it nevertheless suggests something in the works at S&P.

The two charts published at the Guardian from analysts show the unrelenting ascend of Euro Zone government 10-year and 2-year bond yields weighted by each country's GDP, which is a rough approximation of borrowing costs for the entire Euro Zone.

10-year Euro Zone Government Bond Yield Weighted by GDP

(Source: The Guardian, 23 Nov 2011)

2-year Euro Zone Government Bond Yield Weighted by GDP

(Source: The Guardian, 23 Nov 2011)

So far analysts and market players have formulated two possibilities to contain the situation:

Euro Zone sovereign debt pooled in the form of Euro bonds, which would put Germany on the line to implicitly guarantee the peripheral debt

The European Central Bank (ECB) as the lender of last resort by buying up massive quantities of sovereign bonds from indebted euro-zone members

Between the two, we see the Euro bond as the more likely option.

ECB's Euro Zone bond-buying spree of €195 billion since May 2010 has not been successful to contain the interest rate spike, and we doubt more purchases would restore market confidence that much. Moreover, concern over the potential inflationary effect is part of the reason behind German Chancellor Angela Merkel's opposition to ECB expanding its role in bond monetization.

There are market chatters of a potential dissolution or default of the Euro. But some economists believe that the outright collapse of the Euro could reduce GDP in its member-states by up to half and trigger mass unemployment, which could lead to widespread civil unrest and property losses. In that scenario, a recession/depression in Europe and the world would be closer to a probability of 100%.

On the other hand, Euro bond, with the guarantee of the stronger Euro countries, would leverage and facilitate the highly indebted weaker members to get financing at sustainable rates, to repay debt while maintaining some growth. That would in turn benefit other European countries, such as Germany, export business as well.

The failure of the last German bond auction is a reflection of markets losing confidence in the Euro rather than in Germany itself. Without the Germans backing up other troubled sovereign debt, Europe will be increasingly short on cash as investors flee the region. Eventually, Germany would not be immune to an ensuing catastrophic financial system meltdown.

But the Euro bond would only kick the can down the road, and Germany knows it. Germany is reluctant to grant guarantee or fund anything without the peripheral governments' commitment to get their debt and deficit under control. The highly indebted Euro members, on the other hand, are just as reluctant to commit to drastic austerity measures after years of spending way beyond their means. So this is basically the hold-up right now.

During the past 2+ years of this debt crisis in the Euro Zone, Germany, with its strong economy, has emerged as the leader wielding the most power. Euro bond will not achieve its intended purpose without the support of Germany. Europe's future now lies largely in the hands of the German.

Merkel has vehemently opposed the idea of Euro bond, but some within Merkel's governing coalition reportedly are no longer ruling out the introduction of euro bonds. From Spiegel,

"We never say never. We only say: No euro bonds under the existing conditions," Norbert Barthle, budgetary spokesperson for the conservatives in parliament, told the Financial Times Deutschland.

Spain and Italy have the lion's share of the peripheral government debt to mature over the next three years with 2012 being the most critical (See Chart Below)

Working within that timeline, even if busting up the Euro union were a viable option to entertain, the complexity involved with multiple currency conversions would preclude it as something that could be implemented within a year.

Italy, Spain, France and Belgium will each go to market this week to auction bonds worth billions of euros. The outcome of these auctions most likely would push up Euro bond discussion with the Europe decision makers.

Time is basically running out, eventually some compromise, for example, certain GIIPS club member(s) leaving the Union, has to be accomplished to break the current stalemate.

Swift decision making has not been one of Merkel's traits, but the consequence of inaction and delayed action could be much more disastrous for Europe and the world.