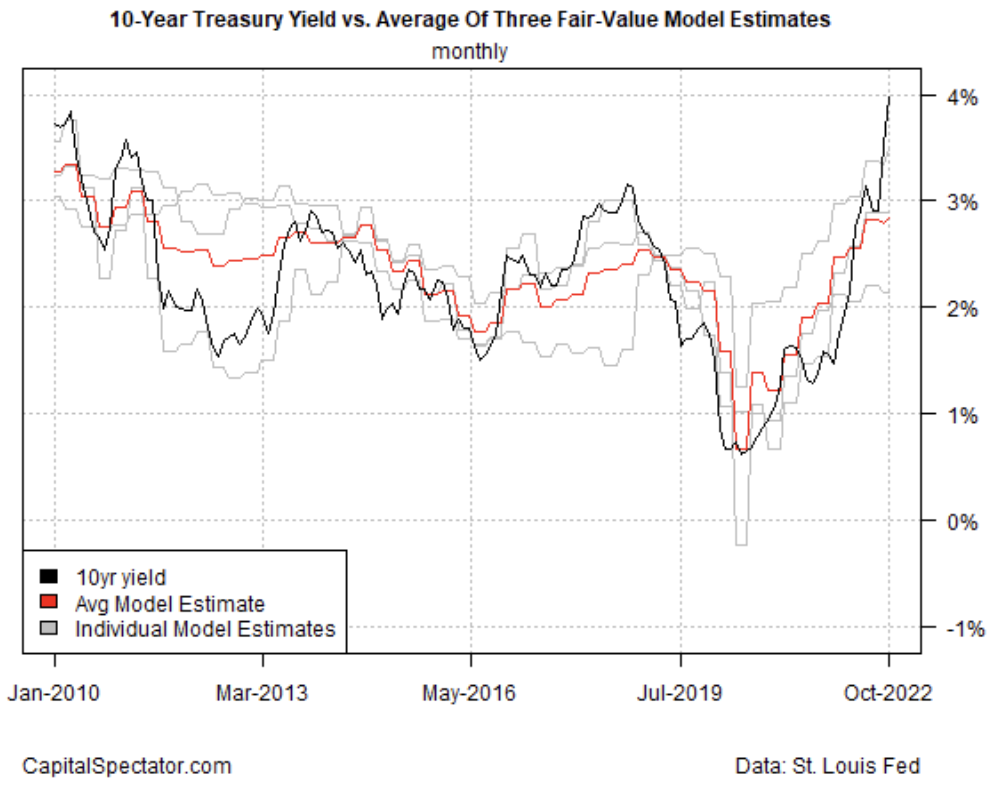

Last month I reported that the ‘fair value’ of the US 10-year Treasury yield appeared “lofty” relative to the average estimate for a combination model. In the weeks since, the benchmark rate has fallen. That’s probably noise, but a month later the model continues to advise that the 10-year rate is lofty.

The 10-year yield settled at 3.83% in yesterday’s trading (Nov. 21), well below the recent peak of 4.25% (Oct. 24). It’s premature to assume that rates won’t rebound and set new highs, but for the moment the market is taking a breather.

Meanwhile, my fair-value estimate, which is built on three models, continues to suggest that macro headwinds are pushing back on higher yields in a stronger degree.

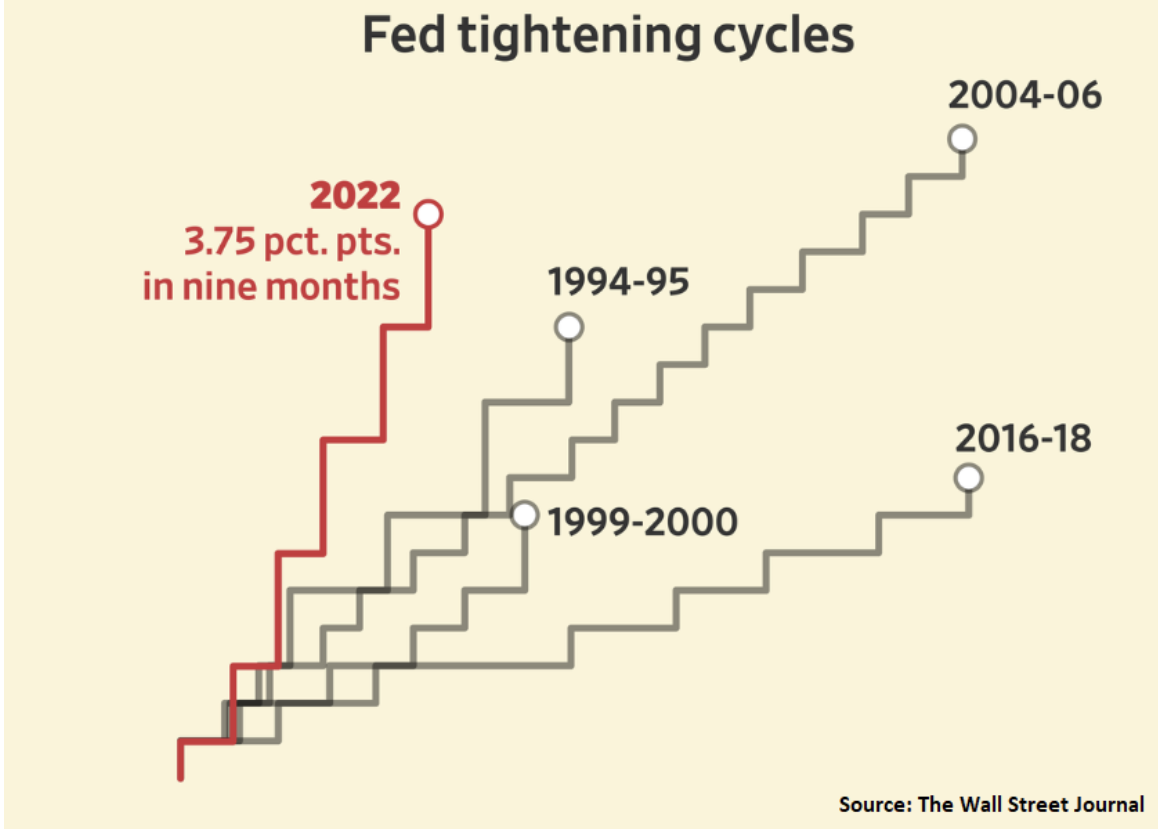

One factor to consider is the Federal Reserve’s ongoing efforts of tightening monetary policy. The rate hikes that began in March are the fastest in four decades and markets are expecting more hikes to come.

Fed funds futures are pricing in a 70%-plus probability of a 50-basis-points hike at the next FOMC meeting on Dec. 14. If correct, the increase would mark the first time the Fed eased its tightening after a series of 75-basis-points hikes to date.

Nonetheless, it’s “premature” to rule out another 75-basis-points increase, says Mary Daly, president of the San Francisco Fed. Although consumer inflation eased in October, “It’s way too early to cause a turning point on inflation. One month does not a victory make. It doesn’t give me comfort,” she explains. “We will need more good months of data before call this a turning point.”

The Fed, of course, can raise rates for reasons that seemingly defy real-time economic logic. That’s partly because monetary policy, as Milton Friedman famously observed, works with long and variable lags. As a result, it will probably take several more months at a minimum before the Fed is comfortable with assuming that inflation has peaked and is no longer a threat to the economy. And that’s assuming incoming inflation data behaves.

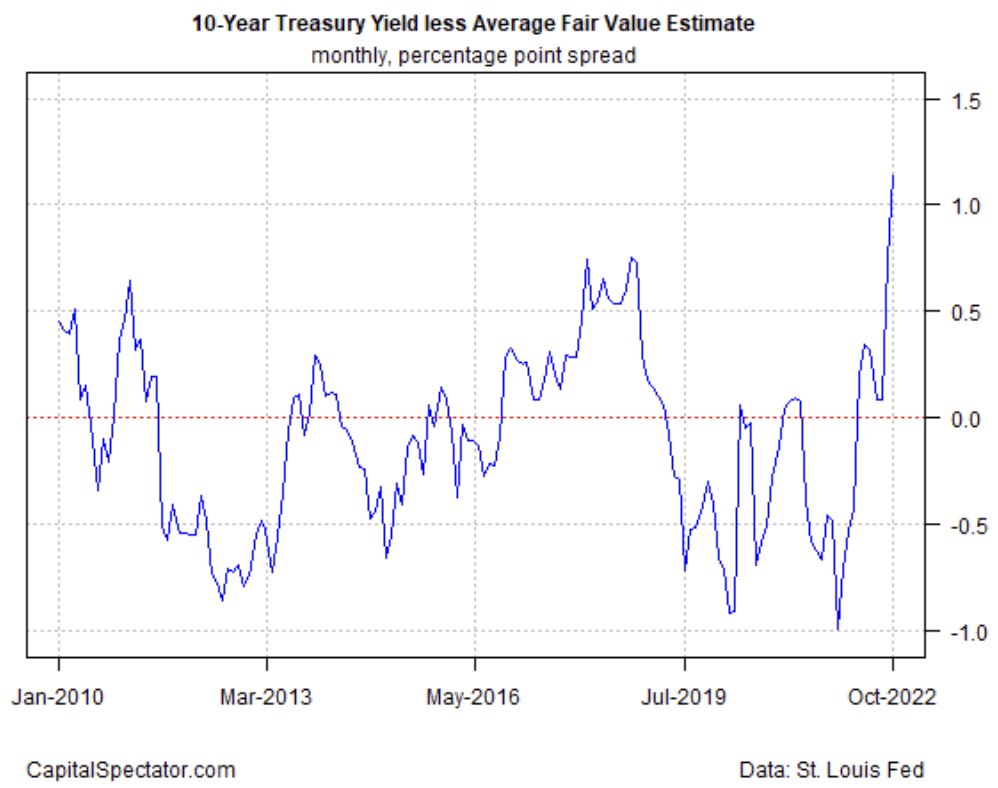

Meanwhile, the headwinds for further increases in the 10-year yield are comparatively strong, based on my modeling. The chart below shows the spread on the market rate for the 10-year less the average model estimate. This alone doesn’t ensure that the market rate can’t rise further, but it’s a factor that suggests that the upside bias for the 10-year yield has faded vs. recent history. The logic here is that the higher the 10-year rate rises over the average estimate, the higher the probability that the market rate will stabilize if not fall.

The key risk for this relatively dovish analysis: upcoming inflation reports turn out to be surprisingly hot. No one can rule out the possibility. But tighter monetary policy is slowing the economy and it’s likely that inflation, if it hasn’t peaked, will do so soon. In turn, the 10-year yield will increasingly reflect this analysis. In fact, there’s a reasonable debate about whether much of this macro outlook is already driving the recent pullback in the 10-year rate.