Inflation rates are diverging more than ever, but mostly due to energy prices

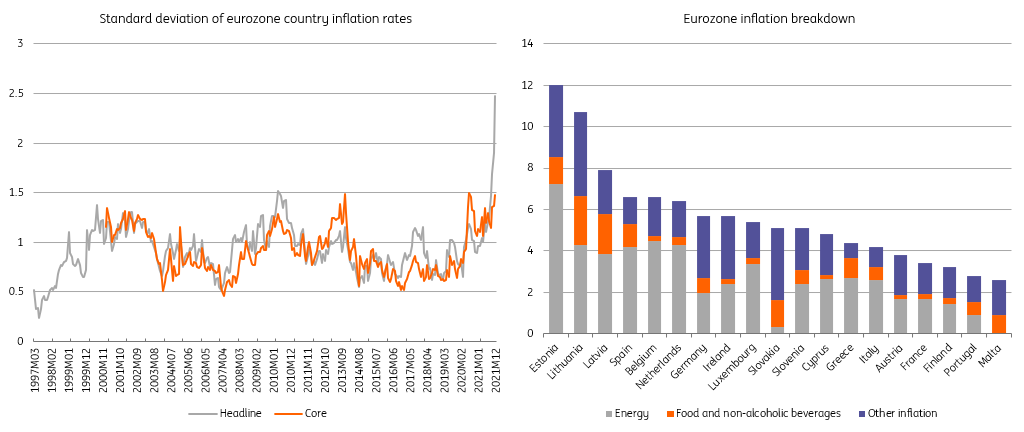

After last Thursday, the European Central Bank looks a lot closer to normalizing or tightening policy. What you hear a lot these days is that it is getting harder and harder for the ECB to steer monetary policy with hugely diverging inflation rates. Indeed, there are massive differences in inflation rates among member states at the moment, from a whopping 12.2% in Lithuania to ‘just’ 3.3% in France. Looking at the standard deviation between countries, we see that this indeed marks the largest divergence between countries’ inflation rates since the start of the monetary union in 1999.

The strong divergence is mainly driven by energy inflation differences between countries. These differences are occurring because of four main reasons: rising market prices for natural gas feeding through to consumers with different delays across countries, the energy mix is different, governments have put different mitigating measures in place and energy has a different share in the inflation basket across countries. When looking at core inflation standard deviations, we see that it is much less pronounced and rather similar to previous peaks experienced in early 2020 and 2013.

But indicators relevant to medium-term inflation are converging…

The current energy crisis can hardly be tackled by monetary policy, though. A central bank can do a lot, but it can hardly fill gas reserves or produce microchips. Central bank policy works less short-term and more medium-term as policy changes move slowly, like an oil tanker. Monetary policy is also much more effective on the demand side of an economy and less so on the supply side. Therefore, the ECB will mainly look at evidence of economies overheating or underperforming as this is an important driver of demand inflation.

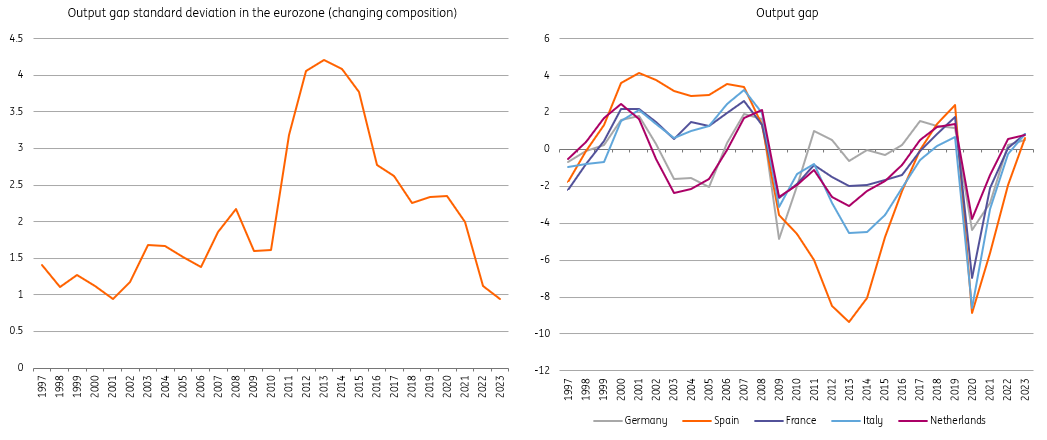

A key indicator for this is the output gap. Yes, we know that this indicator has to be taken with a pinch of salt. Still, it does a decent job at proving our directional point below. The output gap compares current economic output to potential output and we see that the standard deviation for eurozone output gaps has actually been falling steadily since the euro crisis.

Back then, Spain and Italy performed far below potential, while Germany was at or above potential in terms of economic performance. In the aftermath of the dotcom crisis, the divergence between large countries was also large and made policy setting even harder as Spain, France and Italy were performing well above potential while Germany and the Netherlands were well below. In the current crisis, a large output gap opened up everywhere during the first wave, after which strong fiscal support and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program boosted the recovery across the board. Among the larger countries, we still see Spain lagging, but the Spanish economy will be substantially boosted by the EU's recovery fund investment in the coming two years, meaning that the patterns are broadly similar across large economies.

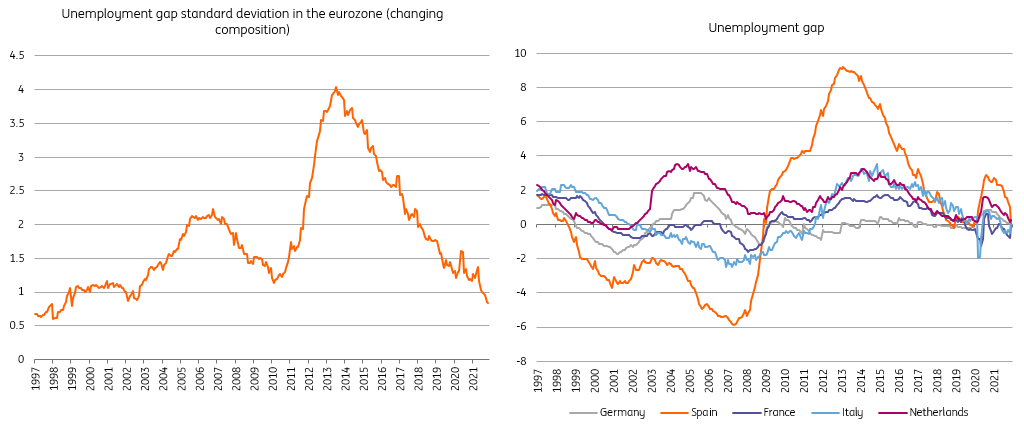

An important driver of output gaps is the labour market and it comes as no surprise that we see declining standard deviations in unemployment gaps in the eurozone. This is an indicator of a labour market with tightness or slack and measures the gap between unemployment and a neutral rate of unemployment below which wage pressures mount. While differences between unemployment are still large between countries, the unemployment gaps are moving much more in tandem. In the euro crisis, southern European economies still saw sizable slack in the labour market while Germany saw unemployment drop significantly. In the current crisis, furlough schemes across Europe and strong economic recoveries have resulted in similar moves between the large economies.

An important driver of output gaps is the labour market and it comes as no surprise that we see declining standard deviations in unemployment gaps in the eurozone. This is an indicator of a labour market with tightness or slack and measures the gap between unemployment and a neutral rate of unemployment below which wage pressures mount. While differences between unemployment are still large between countries, the unemployment gaps are moving much more in tandem. In the euro crisis, southern European economies still saw sizable slack in the labour market while Germany saw unemployment drop significantly. In the current crisis, furlough schemes across Europe and strong economic recoveries have resulted in similar moves between the large economies.

This doesn’t mean that there are no structural differences. Differences in output and unemployment gaps often conceal structural weaknesses in Southern European economies that would benefit from accommodative economic policy for longer to allow for an upward convergence in the eurozone. Even if it is questionable whether monetary policy is well-placed to support this convergence, the experience of the euro crisis has shown that austerity policies and structural reforms alone will not do the trick. In any case, we argue that tighter monetary policy now would be less harmful to the lagging eurozone economies than in previous episodes.

Issues for the ECB to tighten monetary policy are smaller than you might think

For the ECB, this means that while complaints about the one size fits all approach to monetary policy grow louder, the reality is that one size policy actually fits better and better. Certainly better than during the euro crisis and the early 2000s in the aftermath of the dotcom crisis. Most countries are closing the output gap rapidly, indicating that demand-side inflation is returning in the medium term. Some countries still lead the way of course, but leaders and laggards seem closer to each other than in previous crises. In any event, most economies are recovering rapidly and seem able to perform without the current extremely easy monetary stance.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t divergence risks to tightening monetary policy. The main risk is related to debt sustainability in different countries, as debt levels have run up significantly in some eurozone economies. Higher policy rates should not automatically put pressure on debt sustainability but an end to asset purchases and higher bond yields eventually would. This is clearly the story currently priced in bond markets and illustrated by widening spreads since last week’s ECB press conference. Admittedly, governments have used the low interest rate period to roll over debt and to reduce debt costs and the average maturity of outstanding debt is roughly eight years. Consequently, the impact of higher interest rates would take a while to become harmful.

Reacting to widening spreads and debt sustainability across eurozone countries is always very tricky for the ECB. It is always caught between potential monetary financing and ‘only’ ensuring that monetary policy makes its way into the real economy similarly in every eurozone country. Generally speaking, the debt sustainability argument could still change the ECB’s mind on ‘sequencing’, ie first ending net asset purchases and then hiking policy rates. A way out could be to at least bring the deposit rate out of negative territory, while at the same time keeping a small QE floor, or at least using the reinvestment of maturing assets to keep spreads at bay (see also here). Another option could be to start a small new purchase program to keep spreads from widening unsustainably. Clearly, this would come at the risk of pushback from the German Constitutional Court as such a program would once again raise questions about whether asset purchases are a monetary policy instrument solely aimed at the transmission mechanism or covert monetary financing of governments.

At the ECB, there will be plenty of arguments against rate hikes; inflation divergence across the eurozone shouldn’t be one of them.