Investing.com’s stocks of the week

As the ECB currently tries to help PIIGS countries by keeping yields on government bonds down, it does so via the securities market programme (SMP). Rising rates on government bonds of course complicate the prospects for PIIGS governments to manage their finances for several reasons: the budget deficits increase, economic growth deteriorates – or in a worst case slips into negative territory – and debt ratios rise. Hence, it is easy to understand why many countries find it appealing that the ECB should keep rates low through open market operations.

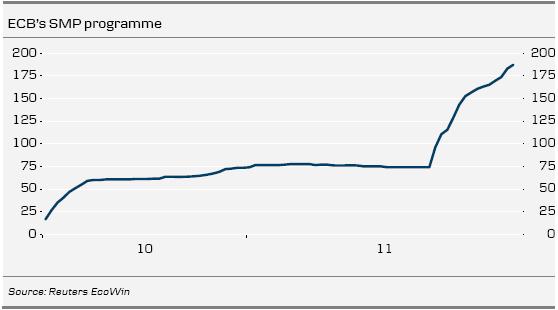

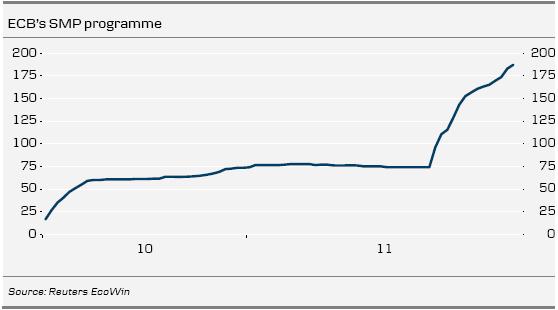

Last week, the ECB’s SMP assets amounted to EUR187bn. When the ECB buys government bonds in the secondary market it adds liquidity to the banks. This liquidity is withdrawn thereafter by using seven-day deposits, so that it exactly “sterilises” the effect of the bond purchase on banks and by extension on overall credit. The ECB can of course choose other ways to withdraw liquidity – i.e. by issuing certificates. Increased liquidity would lead to rising money supply and potentially rising inflation.

“Monetizing the debt” is a situation when a government runs more or less chronic deficits that are financed directly in the central bank (the CB buys the bonds issued directly) and adds it to the balance sheet. Hence, the government can finance its “projects”, such as tax cuts, investments or other types of stimulus at the same time as the monetary base controlled by the central bank increases (the government get credits in the banks). The amount of money in society rises relative to a fixed amount of goods and services – i.e. prices rise in general (inflation).

The ECB cannot buy bonds directly according to its rules. But even current market operations are controversial. Comments from ECB members and German government

officials suggest that they are not happy about continuing to expand the SMP. We note

that Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel says that direct buying is not an option for the

ECB. However, as mentioned, the real difference is probably small.

Is there an inflation risk attached to this? To get a hint, look at the Fed. The American

central bank has launched two QE programmes (quantitative easing, meaning that policy

is eased by adding liquidity to the financial system as the “price” – i.e. the policy rate can no longer be cut – in practice it is zero). In QE1 the Fed bought MBS and other credit

bonds (about USD 1,500bn) and in QE2 it bought Treasuries in the secondary market (USD 600bn). The Bank of England does the same with its programme (about GBP 300bn). Hence, the ECB is only doing the same as others. And so far the scale has been much smaller than others – meaning that inflation risk should at least not be any bigger.

However, Italy and Spain have refinancing needs of some EUR 300bn and EUR 200bn

respectively and on top of that deficits should be financed. Should the ECB raise its ambition for the SMP programme – and there be no fundamental improvement in

government budgets – one might fear that “monetization of the debt” is approaching. That is understandable. But one should keep in mind that EMU countries (PIIGS in particular) are not “expansionary” but rather “contractionary”, which is significantly different from the standard assumption. Current austerity programmes reduce economic prospects and hence inflation pressure. Moreover, taking into account that the financial turmoil, as such, has a negative impact on business and consumer confidence, it is very unlikely that there will be any strong demand for credit at all. And then, there is no inflation pressure. It is likely that the ECB’s swelling balance sheet will get stuck in the banking system as “free reserves”, just like in the US. For those that remember the “quantity theory” of money at A level Economics: M*V = P*Y, where M = money supply, V = velocity of money, P = price level and Y= real GDP. Theory states that if M rises (in this case as the ECB makes its bond purchases) then P will rise, since V and Y are assumed to be fixed. What appears to be happening in reality today is that as P rises V falls to a corresponding degree: no effect on either P (inflation) or Y (real growth). Only the balance sheet of the financial system gets bigger.

What kind of event could change the current extremely depressed sentiment? At the time of writing 10-year Spain and France trades close to 500 basis points above Germany. Finland and Netherlands, are being pulled up too. The expansion of the EFSF appears non-viable as even the chief Regling says that the rising rates in PIIGS means that the “first loss” leverage approach is being dented – i.e. the EFSF may have to take a bigger loss than the 20% being discussed and then the leverage is reduced correspondingly.

It remains to be seen whether the ECB will go against its own principles and start buying bonds in earnest. It seems completely unlikely that it would happen (and what would the political consequences be?), but if some day there is a headline on the Bloomberg screen saying the ECB is buying bonds “unlimited”, then there will be a sharply positive reaction. Spreads are likely to come down and countries would have better preconditions to get their deficits down and stabilise debt. Note that this is not a final solution – it only offers a temporary respite and may even be interpreted as moving to “monetization” – but on the bottom line countries would have to get their finances in order. The alternative is probably to continue muddling through, with rising risks for sovereign bankruptcy and write-downs of banks and other holders of PIIGS assets. It is written in the stars how it will end.

Should this play out, the “good countries” are likely to get hit (yield wise).

On the home front, the supply of events for next week is rather limited. Labour market

developments are likely to be a key factor for the economy next year, we believe it will

rise. But there is no reason to believe next week’s figure will reveal this. The pace of

household lending is declining and the coming figure may possibly suggest whether falling house prices means the trend is accelerating. And what concerns NIER’s confidence survey – we find it hard to believe there has been any radical change to the so far depressed confidence levels. All in all, there is increasing pressure on the Riksbank to start delivering rate cuts from December onwards.

Last week, the ECB’s SMP assets amounted to EUR187bn. When the ECB buys government bonds in the secondary market it adds liquidity to the banks. This liquidity is withdrawn thereafter by using seven-day deposits, so that it exactly “sterilises” the effect of the bond purchase on banks and by extension on overall credit. The ECB can of course choose other ways to withdraw liquidity – i.e. by issuing certificates. Increased liquidity would lead to rising money supply and potentially rising inflation.

“Monetizing the debt” is a situation when a government runs more or less chronic deficits that are financed directly in the central bank (the CB buys the bonds issued directly) and adds it to the balance sheet. Hence, the government can finance its “projects”, such as tax cuts, investments or other types of stimulus at the same time as the monetary base controlled by the central bank increases (the government get credits in the banks). The amount of money in society rises relative to a fixed amount of goods and services – i.e. prices rise in general (inflation).

The ECB cannot buy bonds directly according to its rules. But even current market operations are controversial. Comments from ECB members and German government

officials suggest that they are not happy about continuing to expand the SMP. We note

that Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel says that direct buying is not an option for the

ECB. However, as mentioned, the real difference is probably small.

Is there an inflation risk attached to this? To get a hint, look at the Fed. The American

central bank has launched two QE programmes (quantitative easing, meaning that policy

is eased by adding liquidity to the financial system as the “price” – i.e. the policy rate can no longer be cut – in practice it is zero). In QE1 the Fed bought MBS and other credit

bonds (about USD 1,500bn) and in QE2 it bought Treasuries in the secondary market (USD 600bn). The Bank of England does the same with its programme (about GBP 300bn). Hence, the ECB is only doing the same as others. And so far the scale has been much smaller than others – meaning that inflation risk should at least not be any bigger.

However, Italy and Spain have refinancing needs of some EUR 300bn and EUR 200bn

respectively and on top of that deficits should be financed. Should the ECB raise its ambition for the SMP programme – and there be no fundamental improvement in

government budgets – one might fear that “monetization of the debt” is approaching. That is understandable. But one should keep in mind that EMU countries (PIIGS in particular) are not “expansionary” but rather “contractionary”, which is significantly different from the standard assumption. Current austerity programmes reduce economic prospects and hence inflation pressure. Moreover, taking into account that the financial turmoil, as such, has a negative impact on business and consumer confidence, it is very unlikely that there will be any strong demand for credit at all. And then, there is no inflation pressure. It is likely that the ECB’s swelling balance sheet will get stuck in the banking system as “free reserves”, just like in the US. For those that remember the “quantity theory” of money at A level Economics: M*V = P*Y, where M = money supply, V = velocity of money, P = price level and Y= real GDP. Theory states that if M rises (in this case as the ECB makes its bond purchases) then P will rise, since V and Y are assumed to be fixed. What appears to be happening in reality today is that as P rises V falls to a corresponding degree: no effect on either P (inflation) or Y (real growth). Only the balance sheet of the financial system gets bigger.

What kind of event could change the current extremely depressed sentiment? At the time of writing 10-year Spain and France trades close to 500 basis points above Germany. Finland and Netherlands, are being pulled up too. The expansion of the EFSF appears non-viable as even the chief Regling says that the rising rates in PIIGS means that the “first loss” leverage approach is being dented – i.e. the EFSF may have to take a bigger loss than the 20% being discussed and then the leverage is reduced correspondingly.

It remains to be seen whether the ECB will go against its own principles and start buying bonds in earnest. It seems completely unlikely that it would happen (and what would the political consequences be?), but if some day there is a headline on the Bloomberg screen saying the ECB is buying bonds “unlimited”, then there will be a sharply positive reaction. Spreads are likely to come down and countries would have better preconditions to get their deficits down and stabilise debt. Note that this is not a final solution – it only offers a temporary respite and may even be interpreted as moving to “monetization” – but on the bottom line countries would have to get their finances in order. The alternative is probably to continue muddling through, with rising risks for sovereign bankruptcy and write-downs of banks and other holders of PIIGS assets. It is written in the stars how it will end.

Should this play out, the “good countries” are likely to get hit (yield wise).

On the home front, the supply of events for next week is rather limited. Labour market

developments are likely to be a key factor for the economy next year, we believe it will

rise. But there is no reason to believe next week’s figure will reveal this. The pace of

household lending is declining and the coming figure may possibly suggest whether falling house prices means the trend is accelerating. And what concerns NIER’s confidence survey – we find it hard to believe there has been any radical change to the so far depressed confidence levels. All in all, there is increasing pressure on the Riksbank to start delivering rate cuts from December onwards.