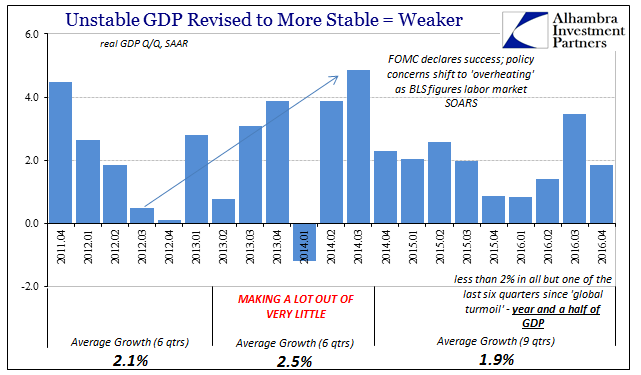

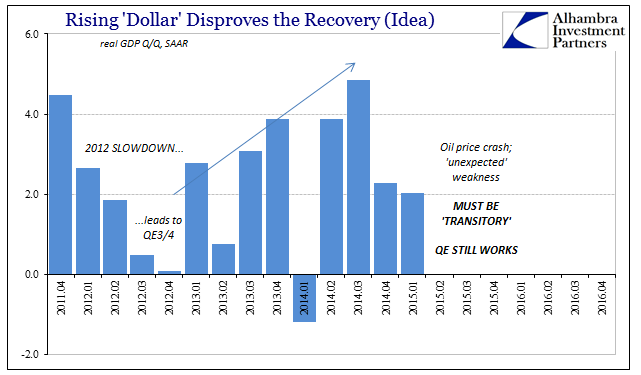

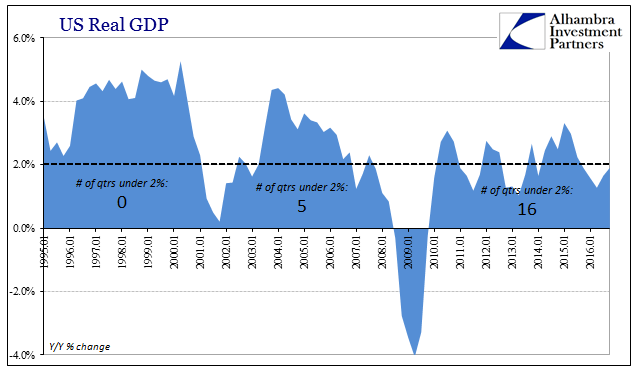

Gross Domestic Product for the fourth quarter of 2016 disappointed once again, which is to say that it was perfectly consistent. At just 1.856%, quarter-over-quarter, it was the fifth time out of the past six quarters less than 2%. Only last quarter where unusual export activity pushed GDP up was the growth rate anywhere close to what it should be for an economy at “full employment.” Instead, we find yet again that good quarters whether in GDP or any other economic account are the anomalies, not those when the snows of winter are so often blamed.

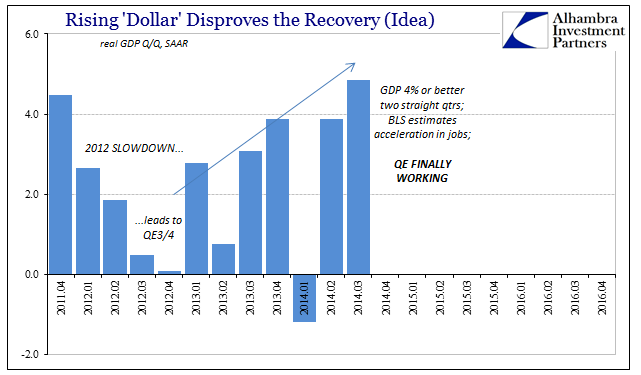

There is now more than enough empirical evidence to show conclusively QE3/4 failed. The entire previous paradigm had depended entirely upon one word, transitory, for it to be revealed otherwise. It has been GDP more than anything else which has likely convinced Federal Reserve officials to abandon both QE and recovery, moving dangerously closer to an embrace (in their own way) of secular stagnation.

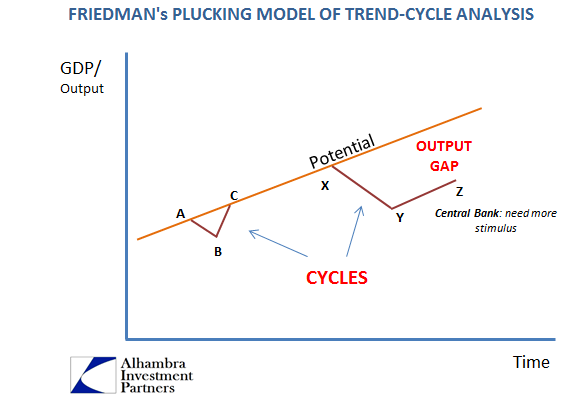

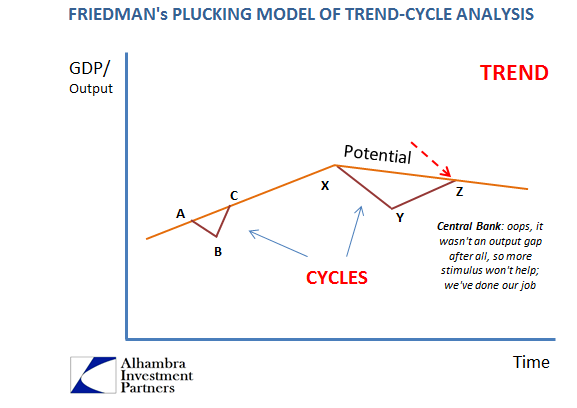

For years, it was believed that the US economy was suffering from a positive output gap, a condition where demand remained less than trend for various possible reasons. The mainstream accepted explanation was something like a balance sheet recession, meaning primarily a deleveraging process after a period of an overly exaggerated debt buildup. The retrenchment in 2012 was judged to be of the same process in an “unexpected” added dose, leading to another global round of “stimulus” including two more QE’s in the US.

Conditions had already appeared significantly better by 2013, but in 2014 it seemed as if deleveraging had finally run its course and that the combination of record high stocks, consumer confidence, and other “stimulus” effects were working, maybe even too well. To arrive at that expectation, however, one had to ignore a whole lot of other statistical and anecdotal evidence that the middle of 2014 was a mirage, itself a temporary reprieve from persistent and persisting malaise and stagnation – starting with Q1 2014 that was never about cold Canadian winds.

We can certainly debate why economists and especially policymakers thought the way they did, starting with pure confirmation bias. They all expected that QE would work and that because what happened in 2008 was a recession and economies always recover eventually from them. Thus, when it appeared in the headline numbers as if things were picking up, that was all they needed to project into full recovery.

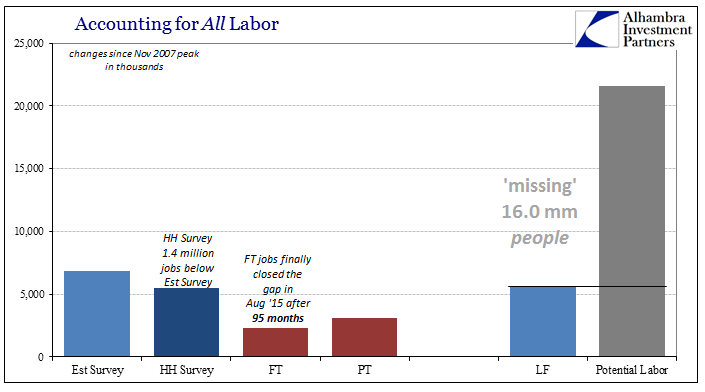

The fact that the unemployment rate was dropping fast meant that the simultaneous approach of “full employment” as well as the high (in their view) possibility of meeting their 2% inflation target would have validated those assumptions, thus to the exclusion of considering all other possibilities (like the denominator for the unemployment rate). The most immediate challenge to this view was the very obvious and stinging oil price crash.

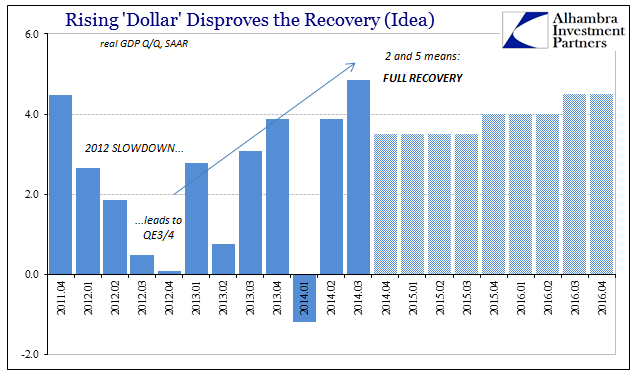

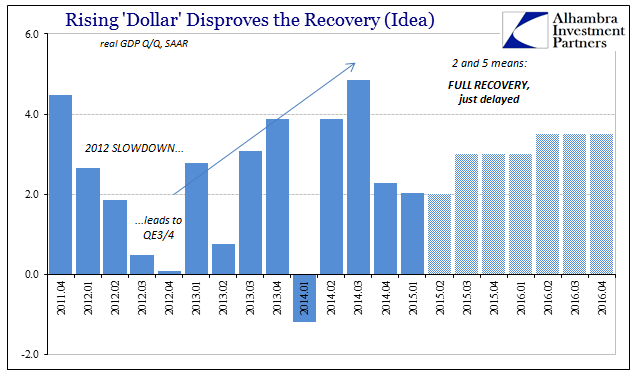

It wasn’t just oil prices, of course, but whatever full form the “rising dollar” took by the middle of 2015 it was rationalized in every way possible. Again, the operative expectation which would have preserved full recovery at the approaching 2 and 5 point was “transitory.” Oil prices, which were claimed to be yet another positive economic condition (boost to consumers), would go back to their prior level taking the CPI and PCE Deflator with them. From this view, QE still worked, full recovery still on the horizon; all that had changed was the timing of it (demonstrated aptly by the FOMC’s great and obvious reluctance to “raise rates” throughout 2015 despite all 2014 expectations that they might be in a hurry to do so).

Even when it became clear that 2015 overall wasn’t going to live up to expectations, “transitory” was simply carried over to 2016. In other words, for the entire prior paradigm of QE and recovery (with the approach of 2 and 5) to be valid the economy in 2016 had to be appreciably better. Were it to turn out not to be, the whole model would have to be reconsidered.

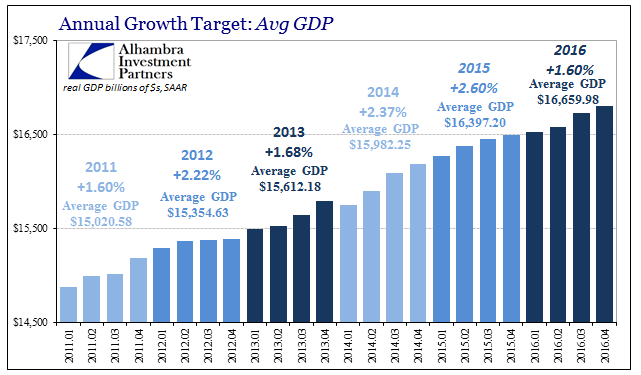

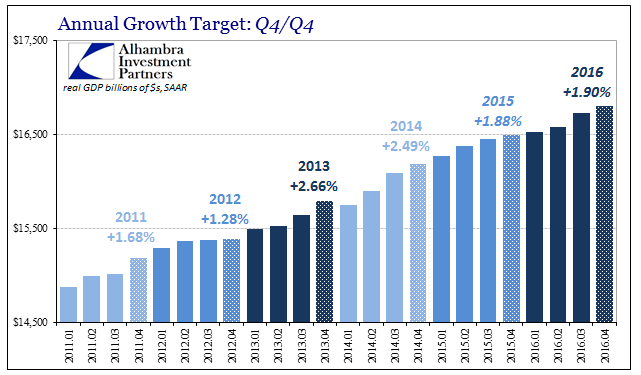

Of course, we know full well that 2016 was just as bad if not worse than 2015. In terms of GDP, however you want to measure it there was nothing left of those 2014 hopes. In terms of average annual GDP, the economy last year was appreciably worse than the year before. Measuring the change Q4/Q4, as is commonly done when analyzing calendar year growth, there was no significant difference between the years, as both were a paltry and, for the recovery idea, devastating 1.9%.

This much was apparent as the likely result far earlier in the year, Q3 aberration aside, which is why sometime around the middle of last year officials and economists completely changed their view. Having finally arrived at the 2 and 5 point only to find a far different economic track as described in constant rather transitory weakness, confirmed by GDP, the orthodox paradigm was given no other choice but to be rewritten if however quietly.

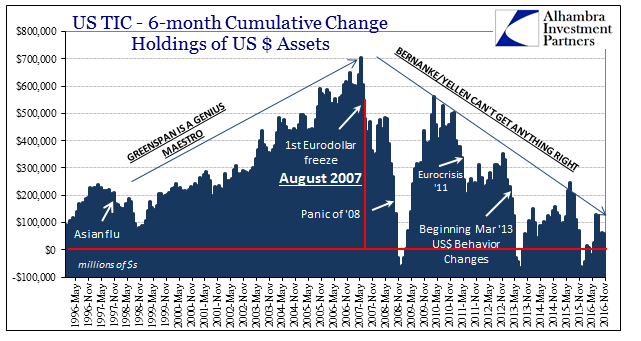

The “rising dollar” didn’t kill the recovery so much as reveal that it was never a realistic option. That should have been the diagnosis from much further back, but even in 2014, again, there were so many warning signs that bias (and some political pressure) is really the only answer as to why they weren’t heeded. Stepping back from GDP in those two middle quarters that year, it was obvious that all “stimulus” wasn’t working (and not just in the US, of course).

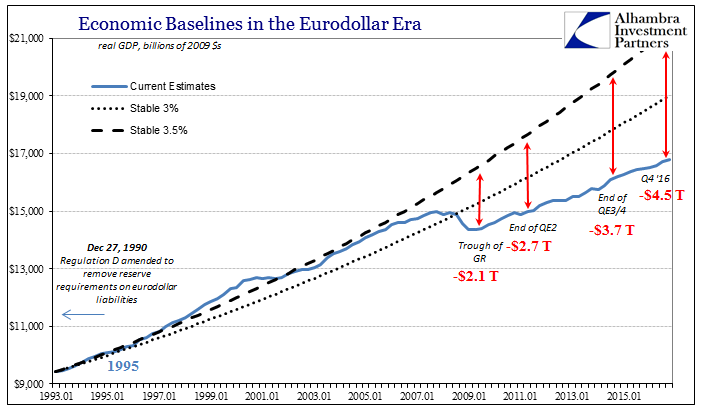

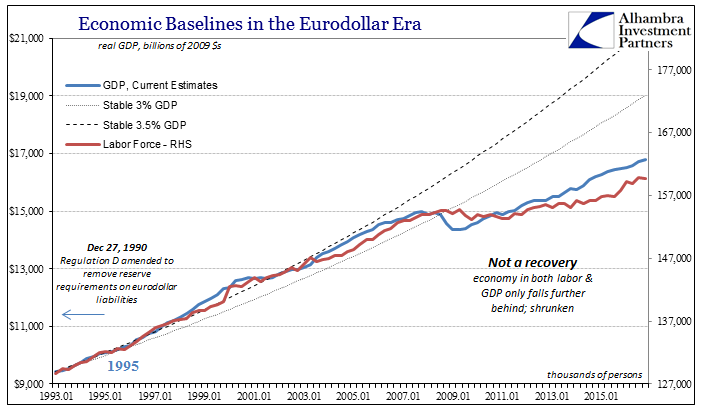

Clearly, the Great “Recession” had left a huge negative imprint, but it wasn’t being erased by either time or official effort. The GDP “output gap” was, roughly, about $2.1 trillion at the trough in Q2 2009. By the end of QE2, just prior to the “dollar” outbreak in 2011, the gap had actually widened to $2.7 trillion. And so it went over time, where no matter what was done or what was expected to occur because of what was done, the distance to the prior trend only grew, the gap widened.

Had the Great “Recession” been a recession, real GDP last quarter would have been $21.3 trillion rather than $16.8 trillion. As of today’s Q4 2016 estimate, real GDP in the US is an unthinkable $4.5 trillion behind what had been a growth baseline dating back decades. How many of our current problems would have receded in importance, if not have vanished entirely, at $21.3 trillion? This is not simply a sluggish recovery, it is something altogether different. It took, however, the Federal Reserve up to 2016 to finally get it, after having wasted so much valuable time.

The Fed, of course, doesn’t actually “get it”, they have only shifted to where reality is but have yet to figure out why simply because they are approaching this new paradigm in as small pieces as they possibly can. Despite what GDP and the labor stats looked like in 2014, in wider context they were perfectly clear in demonstrating what had really been going on all along.

There was never a recovery, and therefore 2 and 5 are totally irrelevant. They are just bureaucratic, institutional nonsense that have prevented necessary awakening to what should have been common sense. You can’t just ignore 10 or 15 million Americans because the economy was so bad they no longer qualified to be included in the bureaucratic definition of the labor force. And it is even more absurd to try to believe that those were all Baby Boomers sailing off into retirement.

This review is no mere academic exercise; it shows very clearly that current officials and economists should not be involved in these next steps. Central bankers, in particular, have a vested interest in protecting their turf (and CYA) rather than finding the truth – especially should it be found, as is most likely, to be a monetary condition behind all of this. That is, in fact, the real reason it had ever gotten so far, as the monetary system, the real monetary system, was the last place they would ever look. That observation really explains not just what happened in 2014 and thereafter but more so everything from the beginning.