China is far from alone in worrying about an investigation by the U.S. Department of Commerce into the impact of imported steel on the U.S. steel industry (due to be announced this week).

The Section 232 investigation is the result of a campaign pledge by President Donald Trump to protect domestic steelmakers against foreign steel imports. Section 232 uses as its test whether imports have been detrimentally harmed the U.S. ability to produce steel for its defense industry, and while it is not country-specific there was little secret at whom it was primarily aimed.

The worry in Europe, generally, and in the U.K. in particular, is that supplies from the region will be caught up in a blanket Section 232 ruling, applying onerous duties that could hit some local steelmakers disproportionately hard.

For example, British steel companies export just 250,000 tons of steel a year to the U.S. For a relatively small industry that only exports 7.6 million tons, that loss could be significant.

The campaign pledge was made against the backdrop of considerable anti-China rhetoric, even though imports of Chinese steel into the U.S. have been falling in recent years.

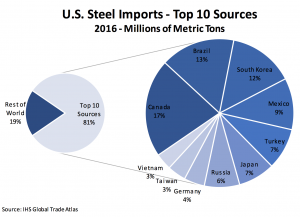

The International Trade Administration of the Department of Commerce recently issued a Global Trade Report, from which this breakdown of source countries was taken:

Not surprisingly, fellow NAFTA countries Canada and Mexico feature in the top five — but so too does Brazil, South Korea, and Turkey, with Japan and Russia only just outside.

The top-10 source countries’ U.S. steel imports make up 81% of the total 30 million metric tons imported in 2016. Non-NAFTA countries like Germany, Brazil and South Korea have all seen volume decreases between 2015 and 2016, while Chinese imports fell 63% putting them in the 11th position. The U.K. dropped 57%, putting them in 14th.

For what it’s worth, European steel suppliers are playing the NATO card, campaigning the Pentagon to argue that imports of steel from the U.S.’s military allies in Europe cannot damage U.S. national security and should therefore be excluded many Section 232 findings.

It’s a nice try on the suppliers’ part, but Trump doesn’t seem to much care for NATO, so it will be interesting to see if that one works.

It’s probable that Europe is not really the target of U.S. steel producers’ concerns over imports. It may be that the NATO card proves of some success if a wider trade war between the two regions is to be avoided.

Either way, major suppliers to the U.S. market in Southeast Asia, South America, Russia and do not have any such argument, in addition to, possibly, NATO member Turkey, which exports a large amount to the U.S. (2.3 million metric tons in 2016, according to the International Trade Administration) and imports a large amount of U.S. scrap.

Those suppliers will be apprehensively waiting for the U.S. Commerce Department’s ruling.

by Stuart Burns