by Moriah Costa

With the SEC's sign-off last week on the proposed revision to the Volcker Rule, it appears banks are getting much closer to something they've wanted for a long time—less regulation.

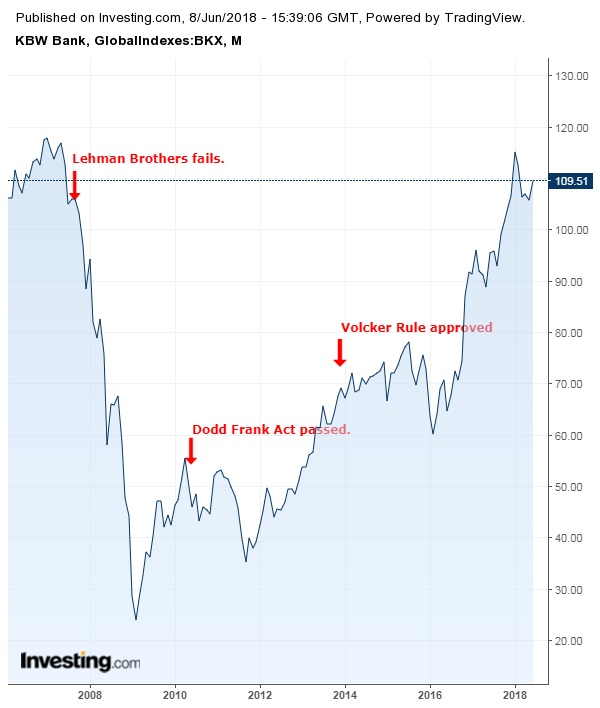

On Tuesday, June 5, the U.S.'s Securities and Exchange Commission became the fifth of five agencies, after the Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), to agree to possible changes to the Volcker rule, a 2013 regulation that prohibits commercial banks from proprietary trading, meaning using customer funds to make speculative investments for the financial institution's own profit.

The rule, part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank banking reform act, was implemented in response to former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker's contention that increased speculative activity by commercial banks in such high-risk financial instruments as derivatives and other specialized securities were a key catalyst of the 2008 financial crisis.

In reaction to the SEC's sign-off on the proposed revision major news outlets, such as the New York Times and CNBC, referred to the changes as “sweeping,” while U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) reacted even more harshly. Referring to the many former Goldman Sachs investment bankers who are, or have been, part of the Trump administration, including current Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin, Warren called it a “favor” by “former banker buddies turned regulators” that rolls back “a rule that protects taxpayers from another bailout.”

Big banks, however, aren't celebrating just yet. Even if the changes actually make it easier for banks to comply with the rule, ultimately those at the top will still be held accountable for any risk financial institutions take on. Most significant, the proposed changes don't get rid of the core component of the regulation, preventing big banks from profiting from bets made with customer money.

While smaller and some mid-size banks (institutions with less than $10 billion in trading assets and liabilities) would become exempt from the Volcker rule, larger banks that make up the bulk of trading by financial entities are not.

Volcker 2.0

The changes to the rule are meant to make it easier for banks and regulators to adhere to the law. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said at the board of governors meeting on May 31:

“The proposal will address some of the uncertainty and complexity that now make it difficult for firms to know how best to comply, and for supervisors to know that they are in compliance. Our goal is to replace overly complex and inefficient requirements with a more streamlined set of requirements.”

The new version, referred to by many as Volcker 2.0, is open for public comment for 60 days before the five bank regulating bodies likely hold a second round of votes later in the year. It has a few core changes.

The first is a modification in categories, which determines how stringently a bank is regulated. Any institution with $10 billion or more in trading assets and liabilities will be subject to the maximum compliance requirements, while any bank with trading assets less than $10 billion but above $1 billion will be subject to alleviated compliance requirements. Finally, any institution with less than $1 billion in trading would be exempt from the Volcker rule.

While critics argue that exempting any banks from proprietary trading regulations is a red flag, Fed staffers estimate that forty banks would still be fully regulated. Those forty—including Bank of America (NYSE:BAC), Citigroup (NYSE:C), JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM), Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS), Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS), and Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)—account for 98% of trading activity.

The second change gets rid of a ban on holding trades for less than 60 days, something even Fed regulators admit is too burdensome. This gives traders more leeway when it comes to placing risky bets on behalf of a client, such as creating trades for a financial product as both the buyer and seller, called market making. Other exceptions include hedging and underwriting an initial public offering.

The new rules instead allow banks to set their own risk and trading strategies, with regulator-approved risk limits. As long as banks stay within those proscribed risk limits, bank examiners will assume the firms are operating within the law.

Other key provisions remain, including bank CEOs being held accountable for any risky trading. This would include proving they had put in place proper controls to prevent proprietary trading.

Simplification Without Undermining Core Principles

The added clarity will make it “easier and cheaper to comply,” said Peter Nerby, Senior Vice President at Moody’s in a note.

“A clarified Volcker Rule that is easier to comply with and enforce, when combined with other post-crisis regulatory enhancements that still require banks to hold greater amounts capital and liquidity for less liquid and more volatile exposures (including the Basel III capital and liquidity framework, the Dodd-Frank Stress Tests, and the Fed’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review), is a credit-positive development.”

Even Paul Volcker, the man who proposed the rule, isn’t against the changes. “What is critical is that simplification not undermine the core principle at stake — that taxpayer-supported banking groups, of any size, not participate in proprietary trading at odds with the basic public and customers’ interests,” he said in a prepared statement.

While some decry the Volcker reforms as a return to the pre-financial-crisis days of risky banking, it remains to be seen if the sector will indeed revert back to the “free for all” that existed prior to the 2008 crisis. For many the new changes mean the opposite: less busy work and more time for regulators to make sure banks don’t bring about another financial crisis.