Deflation risk seems to be making a comeback… again. Germany yesterday sold 5-Year government notes at a negative yield for the first time in its history. Meanwhile, China’s central bank this week warned that the threat of deflation is rising for the world’s second-largest economy. Europe and Japan, of course, continue to struggle with lowflation/deflation. The US is doing better, thanks largely to stronger growth, but inflation is low and may get lower still. “The problem is that aggregate prices are dipping in so many places at once,” The Economist reminds.

Today’s update on US consumer prices is expected to deliver more of the same. Headline inflation is projected to turn a deeper shade of red in the monthly comparison for January—a decline of 0.6% vs. a 0.4% slide in the previous month, according to the consensus forecast via Econoday.com. Core inflation will remain relatively steady and slightly positive, economists predict, but the general outlook is for low inflation with the potential for a downside bias.

The Fed’s Janet Yellen yesterday reiterated that the central bank would prefer to see inflation moving closer to its 2% target before it begins raising interest rates. At the moment, however, that’s an unlikely scenario. Year-over-year inflation is running at roughly half the Fed’s target, although Yellen cited forecasts that see higher levels in the months ahead. She also said that lowflation wouldn’t necessarily be a deal breaker for tightening monetary policy; instead, the labor market would remain the key variable for deciding when to start hiking rates.

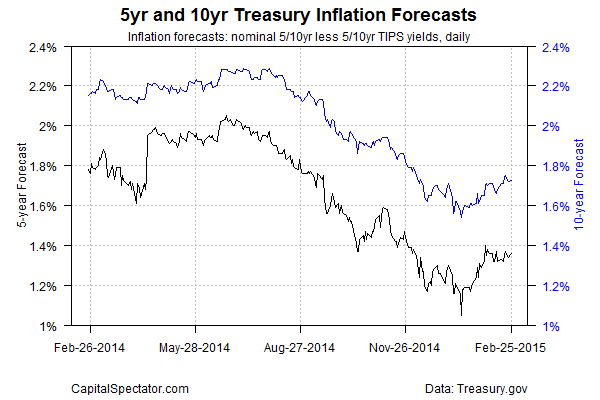

There’s a degree of support in the Treasury market for thinking that inflation may inch higher. Implied inflation expectations via the yield spread on nominal and inflation-linked government bonds are modestly higher, albeit after a months-long slide.

The question, of course, is whether US inflation can move closer to the Fed’s 2% target at a time when the rest of the world is battling disinflation/deflation? Perhaps if energy costs are now set to stabilize we’ll have a foundation for firmer pricing generally. Confidence for this scenario will get a boost if the recent signs of growth in the Eurozone turn out to be more than another false dawn.

The European Commission currently sees a mildly favorable trend emerging via its new economic outlook. Growth for the Eurozone is now projected at 1.3% for this year, a touch higher than the previous 1.1% forecast. Better, but that’s a thin reed for keeping deflation at bay. On the other hand, weaker growth at this stage would be rather ominous at a time when deflation risk is elevated. The same caveat applies elsewhere.

In fact, all this highlights a bigger risk: the next recession. As The Economist notes,

Most rich-world central banks have already cut their main policy rates near to zero in order to pep up demand. A growing number of European economies are using negative interest rates to encourage spending, although charging people to put money in the bank will eventually prompt them to use the mattress instead.

All of which means that policymakers risk having precious little room for manoeuvre when the next recession hits. And sooner or later it will—because of a sharp slowdown in China, say, or the effect of a rising greenback on dollar-denominated corporate debt, or from some shock that comes out of the blue. The Federal Reserve has cut its policy rate by an average of 3.9 percentage points in the six recessions since 1971. That would not be possible today. The break-glass-in-case-of-emergency option of depreciating the currency massively against a fast-growing trading partner is of limited use when so few big economies are growing rapidly and prices are falling, or close to it, in so many places.

Business-cycle risk on steroids, you might say. The good news is that recession risk in the US is currently low. It’s higher in Europe, but perhaps the threat is receding if the nascent recovery is sustainable. China’s economy is slowing but no one thinks an outright recession is likely anytime soon.

The real issue, then, is deciding if central banks can normalize policy before the next economic slump strikes? Even an optimist must concede that it’s going to be a close call.