After 40-years of economic erosion, there are still deficit deniers.

The belief that debt and deficits “don’t matter” primarily stems from the basis the economy hasn’t collapsed and become a historical equivalent of Weimer, Germany. However, the rather elementary view fails to distinguish that dropping a frog into boiling water or slowly bringing the water to a boil equates to the same outcome. That latter just takes longer to get there.

A recent article by Barry Ritholtz entitled “Time To Stop Believing The Deficit Bullshit” is an interesting read. It makes a logical argument as to why running massive deficits doesn’t seem to matter. (Such is the basis for Modern Monetary Theory)

“We are told (over and over, again and again) that if we allow the federal government to deficit spend, a parade of horrors awaits us, including:“

- Excess Federal spending will crowd out Private Capital, choking innovation and new company formation;

- The costs of US borrowing will skyrocket, making the debt impossible to manage;

- The US Dollar will be devastated, and it will be radically devalued against all other currencies;

- All of this will cause rampant inflation, spiking prices to levels not seen before;

- Deficits will act as a drag on the overall economy;

“It has been 50 years of hearing this — and NONE OF IT HAS PROVEN TRUE. So I am calling bullshit on this — and you should, too.”

On the surface, everything he states is correct. We haven’t seen the destruction of the underlying economy over the last couple of years from running a massive deficit.

In other words, deficits didn’t seem to drop the economy into a vat of boiling water.

But just because the evidence isn’t obvious, does that mean it doesn’t exist? For that answer, we must take a longer-term view.

Not All Deficit Spending Is Bad

In “Learn To Love Deficits,” I quoted Dr. Woody Brock, author of “American Gridlock,” on the critical distinctions between good and bad deficit spending. To wit:

“The problem is that these progressive programs lack an essential component of what is required for ‘deficit’ spending to be beneficial – a ‘return on investment.’

Country A spends $4 Trillion with receipts of $3 Trillion. This leaves Country A with a $1 Trillion deficit. In order to make up the difference between the spending and the income, the Treasury must issue $1 Trillion in new debt. That new debt is used to cover the excess expenditures but generates no income leaving a future hole that must be filled.

Country B spends $4 Trillion and receives $3 Trillion income. However, the $1 Trillion of excess, which was financed by debt, was invested into projects, infrastructure, that produced a positive rate of return. There is no deficit as the rate of return on the investment funds the “deficit” over time.

There is no disagreement about the need for government spending. The disagreement is with the abuse and waste of it.

John Maynard Keynes’ was correct in his theory that in order for government ‘deficit’ spending to be effective, the ‘payback’ from investments being made through debt must yield a higher rate of return than the debt used to fund it.

Currently, the U.S. is ‘Country A.”‘

As Barry aptly notes, using deficit spending for projects that have a “return on investment” such as power production (geothermal, nuclear, tidal) or broadband, all of which users pay a fee to consume, is valid. Such is because the long-term revenue generated by these projects repays the debt over time.

Using deficit spending to fund social welfare programs has a long-term negative multiplier to economic growth.

Boiled Alive By Deficits

Barry is also correct that surging deficits have not led to a noticeable collapse in the dollar, private capital, rampant inflation, slower economic growth, and surging borrowing costs. However, like bringing the water to a slow boil, the frog doesn’t realize it is trouble until it’s too late.

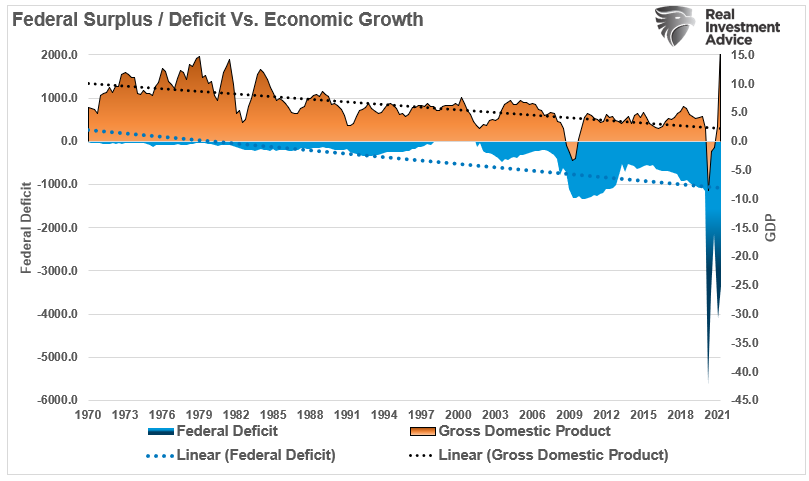

The government’s serious endeavors into deficit spending began with Ronald Reagan in 1980. Since then, politicians concluded that a lot should be better if a little deficit spending is good. But, importantly, there only seems to be the positive benefits of a boost in activity and getting re-elected to office.

In the longer term, however, the water temperature is clearly on the rise.

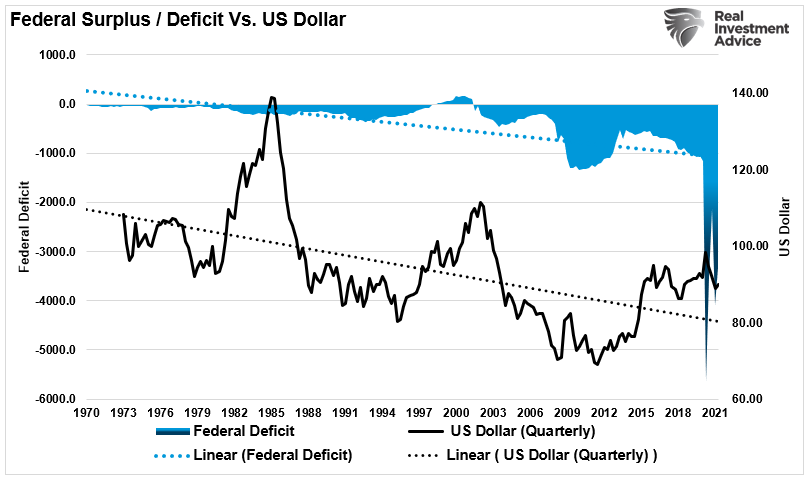

While the dollar hasn’t collapsed under the weight of deficit spending, the negative strength trend relative to other currencies is clear.

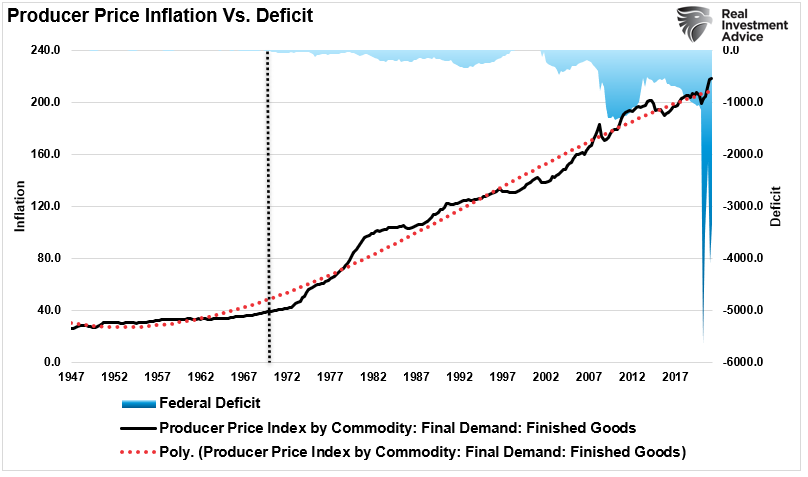

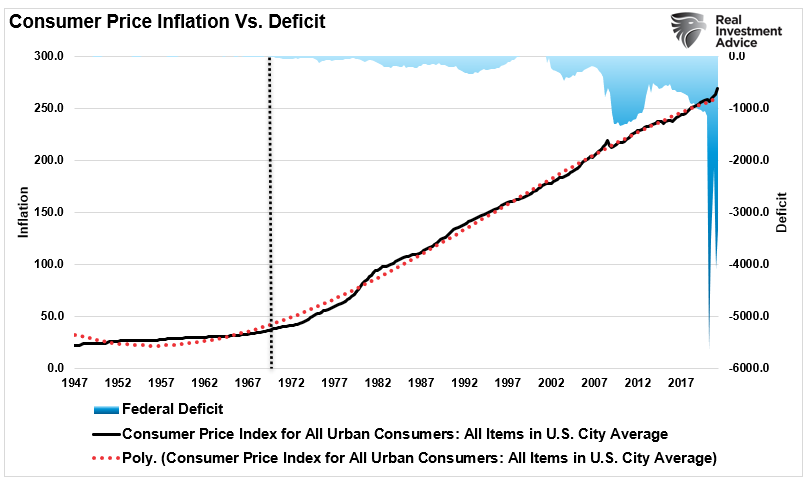

Of course, as the dollar weakens and deficits grew, Inflation, for both producers and consumers, rose.

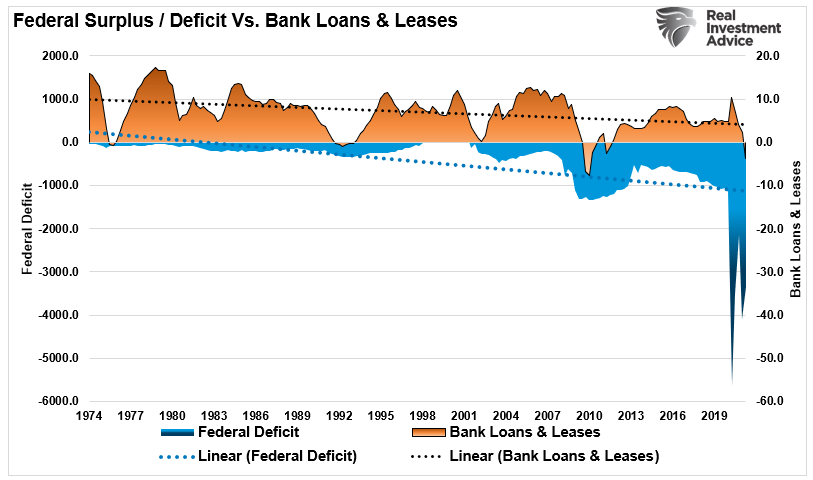

While it may not appear that deficits are crowding out private investment, the rise of behemoth companies like Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL), and others, do crowd out innovation and new company formations. Such activities require capital, and there is a reasonable correlation between the ebbs and flows of deficits and capital acquisition.

Not surprisingly, as the dollar weakens, the movement of capital slows, and inflation rises, the rate of economic growth slows. Such should not be surprising as debt used for non-productive purposes diverts money away from productivity to interest service.

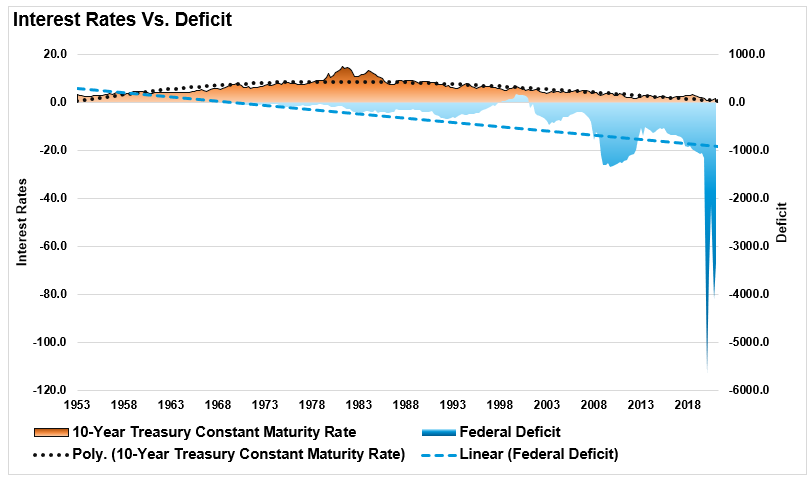

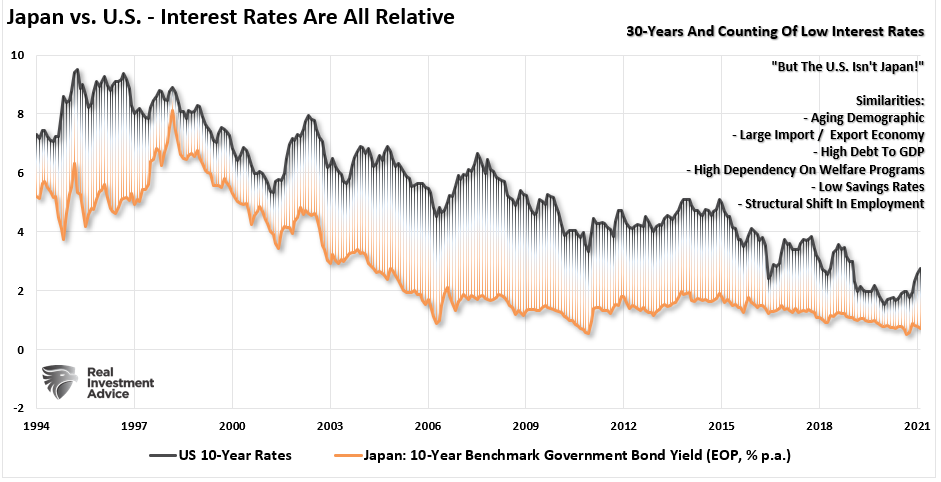

The one thing that deficits have not led to is surging interest rates and massive increases in borrowing costs.

However, that suppression of interest rates has come from two primary sources.

- Slower rates of economic growth

- Massive interventions by the Federal Government to suppress rates.

But what about Japan?

The Japan Syndrome

As Barry notes:

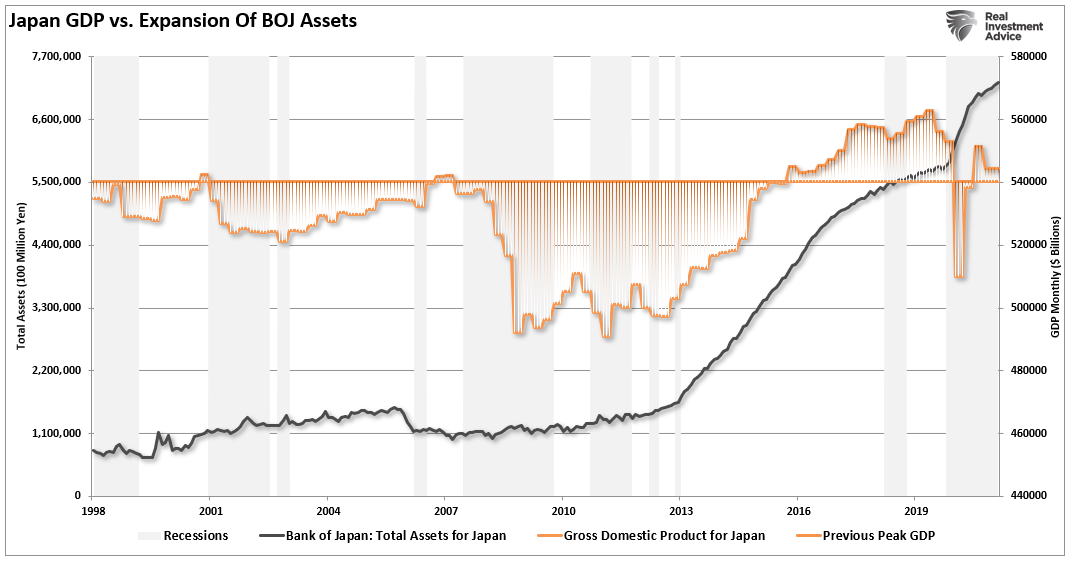

“Not that we want to be like Japan, but their Public Debt to GDP ratio is 275%; in the U.S., it is 102%. None of the bad things about the Yen or private capital or borrowing costs have occurred. Japan can still borrow all it wants, and at very low rates, too.”

While he is correct the U.S. isn’t Japan, yet, I am not sure such is a template we want to follow.

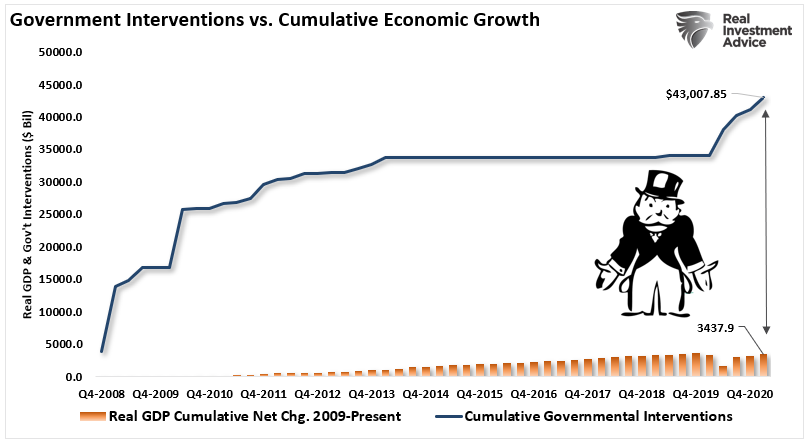

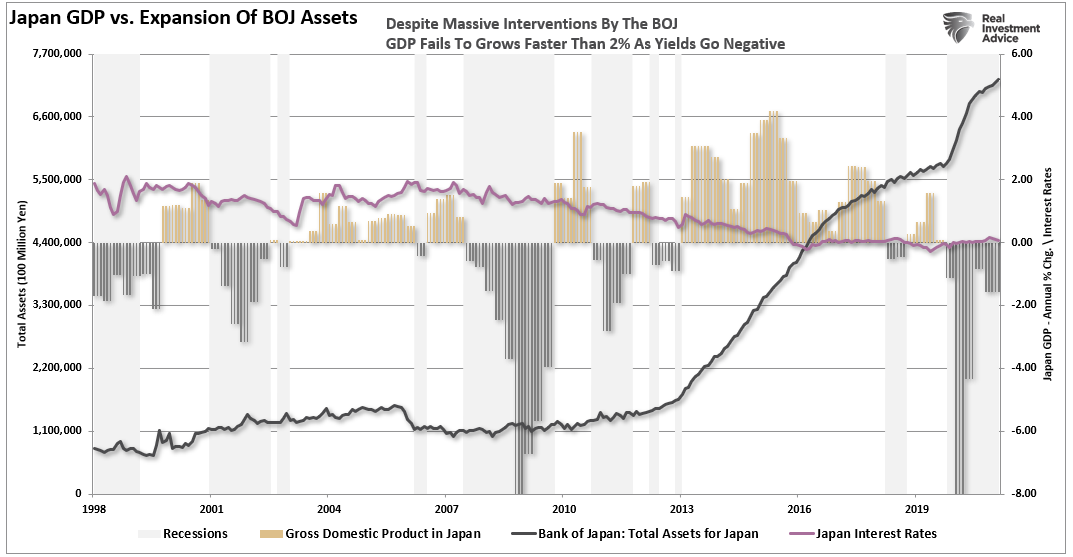

“Since the financial crisis, Japan has been running a massive “quantitative easing” program, which, on a relative basis, is more than 3-times the size of that in the U.S. Despite that massive surge in Central Bank interventions, it, like the U.S., has had little effect on economic prosperity.”

“Japan remains plagued by rolling recessions and low inflation, and low-interest rates. (Japan’s 10-year Treasury rate fell into negative territory for the second time in recent years.)”

Why is this important? Because Japan is a microcosm of what is happening in the U.S. As I noted previously:

“The U.S., like Japan, is caught in an ongoing ‘liquidity trap’ where maintaining ultra-low interest rates are the key to sustaining an economic pulse. The unintended consequence of such actions, as we are witnessing in the U.S. currently, is the battle with deflationary pressures. The lower interest rates go – the less economic return that can be generated. An ultra-low interest rate environment, contrary to mainstream thought, has a negative impact on making productive investments, and risk begins to outweigh the potential return.”

Japan is a template of the fragility of global economic growth.

Japan tried to substitute monetary policy for sound fiscal and economic policy. And the result is terrible.

The Deficit Middle-Ground

Barry is correct that there is a middle ground on deficit spending.

Should governments use deficit spending for “productive investments” during periods of economic downturns? That answer is clearly in the affirmative category.

However, once the economy returns to growth, the deficits should get reversed into surpluses to prepare for the next inevitable downturn. Such is the entire underlying premise of Keynesian economic theory. But, unfortunately, politicians, in their ongoing endeavor to get reelected, just ignored the part of repaying debts.

While short-term deficits may have no consequences, the rising levels of corporatism, wage disparities, and wealth inequality provide ample evidence that something has gone wrong.

Are all the problems in the U.S. solely the result of unbridled deficit spending? Of course, not. The U.S. has spent four decades making poor political and economic choices as well.

- Massive increases in consumer and corporate debt.

- A shift from productive to non-productive labor.

- Poor immigration policies.

- The slow erosion of the rule-of-law; and,

- An undermining of capitalism and move to socialistic policies.

If you ignore all of the anecdotal evidence, an argument can get made for running continual economic deficits. However, suggesting “deficit hawks” are wrong is incorrect.

We can continue the path we are on for quite some time, and probably longer than most imagine.

But, just because we haven’t realized it yet, doesn’t mean we aren’t slowly being “boiled by deficits.”