The coronavirus crisis has reordered expectations and valuations in global markets, but searching for the deepest discounts (based on negative return) delivers a familiar result: the commodities realm continues to offer the darkest shade of red.

The concept of value investing generally, thanks to weak results, has come under renewed scrutiny, again, in recent history. By some accounts, the notion of buying assets on the cheap and expecting to earn a relatively high-risk premium for the effort has become null and void in the 21st century. Die-hard advocates of the value factor respond: Baloney! We’ve been here before and value’s dry spell will, once more, give way to its historical pattern of generating high absolute and relative returns to patient investors willing to tolerate short-term pain. By that reasoning, overweighting value, in one or more of its various guises, will continue to provide opportunities for portfolio design and asset allocation.

While we wait for Mr. Market to sort out this debate, let’s catch up with the numbers on the value front through a performance lens. But first, a quick refresher on the ranking system used below.

The metric of choice for “deep value” in this column is the 5-year return, which is based on an idea outlined in a paper by AQR Capital Management’s Cliff Asness and two co-authors: “Value and Momentum Everywhere,” published in a 2013 issue of the Journal of Finance. There are numerous value metrics and so no one should confuse the 5-year-performance benchmark as the definitive measure of bargain-priced assets. But as a starting point in the process of identifying where the crowd’s expectations have stumbled, the 5-year change is a useful metric.

One advantage of using a 5-year performance measure: It can be applied over a broad set of assets, thereby dispensing a level playing field for evaluating value (or the lack thereof). Another plus: this metric is simple and therefore immune to estimation risk, which can complicate accounting-based value gauges, such as price-to-book and price-to-earnings measures. In short, the 5-year return is a handy tool as a first approximation for identifying ETFs that appear to be deeply discounted by the crowd — and thereby seem to offer relatively high expected returns via the value proposition for investing.

But before you rush in this door, keep in mind that the standard caveat applies, namely: there are no guarantees that value, no matter the definition, will lead to superior performance anytime soon, if ever. Recent history suggests no less. All the more so when it comes to commodities– fossil-based energy investments in particular. As the world grapples with the risk of climate change, there are predictions that the glory days for oil companies and the like are behind us. In sum, traditional energy companies are deeply discounted for a reason and so investors should proceed with caution in this space.

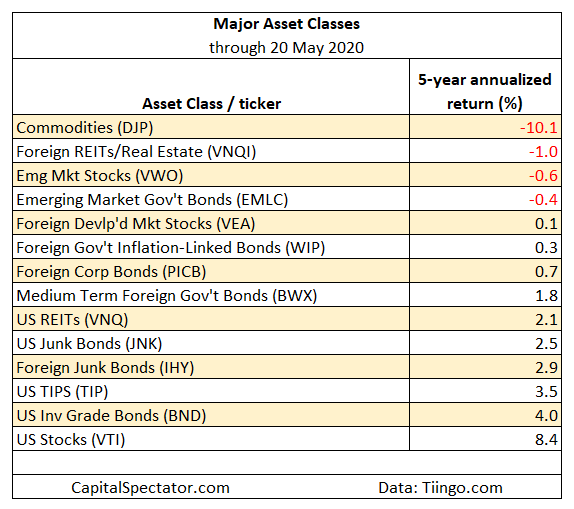

The ranking below covers 135 exchange-traded products that run the gamut: US and foreign stocks, bonds, real estate, commodities and currencies. You can find the full list here, sorted in ascending order by annualized 5-year return — 1260 trading days — through yesterday’s close: May 20, 2020.

Keep in mind that the list is quite granular. In equities, for instance, the ETFs range from broad regional definitions (Asia, Latin America, etc,) to country funds, down to US sectors (energy, financials, for instance) and industries (e.g., oil & gas equipment & services). The only limitation is what’s available for US exchange-listed funds. Note, too, that just one representative ETF for each market niche is selected, albeit subjectively. For instance, there’s only one fund on the list for US real estate investment trusts. Otherwise, the search is broad and deep, as allowed by the current availability of US-listed ETFs.

Let’s start by ranking the major asset classes. Once again, a broad definition of commodities continues to post the deepest shade of red for 5-year results, echoing the results in CapitalSpectator.com’s previous value review in January. The iPath Bloomberg Commodity (DJP) – an exchange-trade note – has lost an annualized 10.1%. Foreign real estate shares, along with emerging-markets stocks and bonds, are also posting sub-zero returns, albeit mildly so.

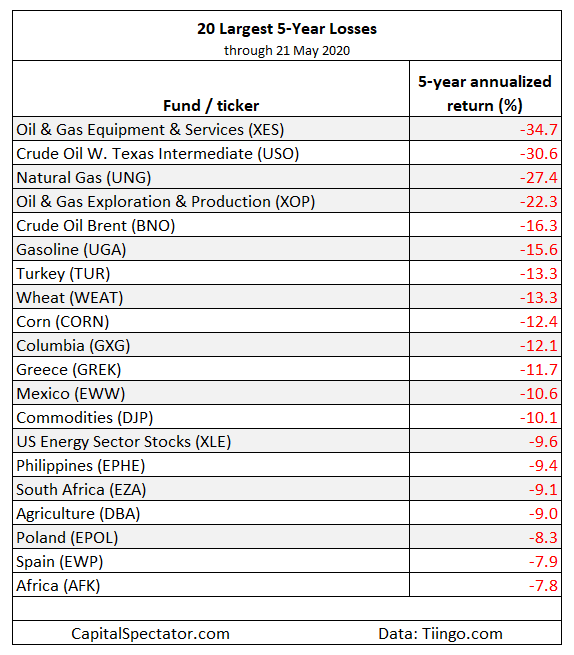

Let’s drill down into the specifics and focus on the deepest 20 losses for all 135 ETFs. The biggest decline at the moment is in oil patch stocks via SPDR Oil & Gas Equipment & Services (XES), which has lost an astonishing 34.7% a year for the past five years.

XES has been ailing for some time. The question is whether it will recover? Looking through value-corrected glasses leaves room for optimism. Stay tuned for Mr. Market’s verdict.