Definitive stock market patterns arise over very long time periods. This data can help us figure out where we are today.

The price data for the 30-stock Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) goes back to 1896 (116 years). This deep history is an excellent resource for gaining insight into market cycles.

Note: The DJIA has contained 30 stocks only since 1928. From 1916 to 1928 the number was 20 and from inception in 1896 to 1916 there were 12 stocks in the index.

Follow up:

The data for the broader S&P 500 index ($SPX) doesn’t go back as far. But since the two indexes shadow each other, the results discussed here also generally apply to the broader market.

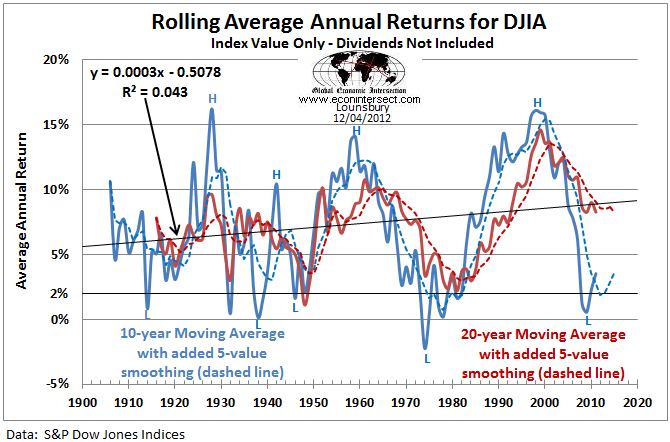

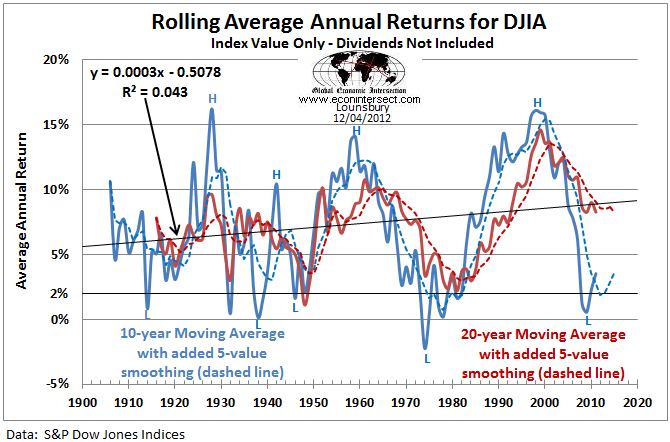

Take a look at the chart below (“Rolling Average Annual Returns for DJIA”).

The blue and red lines represent the 10-year and 20-year rolling averages of annual price changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Rolling averages are used because if we were to plot annual returns, there would be a bunch of points with no distinguishable pattern, or what statisticians call “noise.”

The dashed lines are even more of an abstraction. They represent the averaging of five-year periods within the 10- and 20-year periods. The result is less noise, but the amount of usable, detailed information is limited.

Findings of Interest

The chart clearly shows that long-term price movements are cyclical. No surprise there.

But here’s what is interesting: in the last several decades, the cycles have been of longer duration and of greater magnitude.

It gets even more interesting if we focus on the cyclical highs and lows. On the graph, we have labeled cycle highs (H) and lows (L) in the 10-year rolling average. The definition of highs and lows is given in this table below (“Qualifying 10-year M.A. Highs and Lows”).

The highest of the qualifying highs between the two cycle lows is labeled as the cycle high, and the cycle lows are similarly determined.

In the past century or so, there have been eight market lows—defined as the 10-year rolling average at or below 2 percent. But only half of these lows—four to be exact—have actually been cycle lows.

There have been six market highs, and most of these (four) have been actual cycle highs.

What does this mean? Over the past century, it has been much less clear when the stock market had bottomed, since market lows weren’t necessarily the actual cycle bottoms. By contrast, cyclical tops in the market have been less ambiguous.

Takeaways for Investors

In our current cycle, pundits are saying stocks bottomed in March 2009. But if history is any guide, that may not be the case. Another cyclical low perhaps awaits us. For that reason, our High/Low table shows a question mark after the “L” next to 2009. It will take some time to be sure there isn’t a lower low coming.

Another sign of caution: the high level of our current 20-year rolling average. In past cycles, that has been much lower than the level reached to date.

One cause for optimism: there is a clear upturn in the 5-value smoothing curve (the dashed blue line). In the past, that has been a reliable signal that the cycle low had passed.

Another interesting aspect is cycle duration, indicated by the intervals shown in the last column of the table. Most of the cycles (five out of eight) have occurred over 10 to 15-year intervals. The two four-year intervals around World War II are anomalies.

The 24-year interval between the last verifiable cycle is truly exceptional (from the cycle low in 1974 to the cycle high in 1998). As you can see, no other intervals in the past century have been nearly as long. This can perhaps be explained by the activist monetary policy that started in the 1980s. The Federal Reserve has stepped in quickly with monetary fixes during each period of economic distress.

So where does that leave us? If 2009 was indeed the current cycle’s bottom, that means 11 years will have passed between cycle high and low. That is within the 10 to 15-year range for cycle intervals. But only time will tell if that is long enough to digest the excesses fostered by the abnormally long 24-year interval in which the market was advancing, without a cycle low.

The price data for the 30-stock Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) goes back to 1896 (116 years). This deep history is an excellent resource for gaining insight into market cycles.

Note: The DJIA has contained 30 stocks only since 1928. From 1916 to 1928 the number was 20 and from inception in 1896 to 1916 there were 12 stocks in the index.

Follow up:

The data for the broader S&P 500 index ($SPX) doesn’t go back as far. But since the two indexes shadow each other, the results discussed here also generally apply to the broader market.

Take a look at the chart below (“Rolling Average Annual Returns for DJIA”).

The blue and red lines represent the 10-year and 20-year rolling averages of annual price changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Rolling averages are used because if we were to plot annual returns, there would be a bunch of points with no distinguishable pattern, or what statisticians call “noise.”

The dashed lines are even more of an abstraction. They represent the averaging of five-year periods within the 10- and 20-year periods. The result is less noise, but the amount of usable, detailed information is limited.

Findings of Interest

The chart clearly shows that long-term price movements are cyclical. No surprise there.

But here’s what is interesting: in the last several decades, the cycles have been of longer duration and of greater magnitude.

It gets even more interesting if we focus on the cyclical highs and lows. On the graph, we have labeled cycle highs (H) and lows (L) in the 10-year rolling average. The definition of highs and lows is given in this table below (“Qualifying 10-year M.A. Highs and Lows”).

The highest of the qualifying highs between the two cycle lows is labeled as the cycle high, and the cycle lows are similarly determined.

In the past century or so, there have been eight market lows—defined as the 10-year rolling average at or below 2 percent. But only half of these lows—four to be exact—have actually been cycle lows.

There have been six market highs, and most of these (four) have been actual cycle highs.

What does this mean? Over the past century, it has been much less clear when the stock market had bottomed, since market lows weren’t necessarily the actual cycle bottoms. By contrast, cyclical tops in the market have been less ambiguous.

Takeaways for Investors

In our current cycle, pundits are saying stocks bottomed in March 2009. But if history is any guide, that may not be the case. Another cyclical low perhaps awaits us. For that reason, our High/Low table shows a question mark after the “L” next to 2009. It will take some time to be sure there isn’t a lower low coming.

Another sign of caution: the high level of our current 20-year rolling average. In past cycles, that has been much lower than the level reached to date.

One cause for optimism: there is a clear upturn in the 5-value smoothing curve (the dashed blue line). In the past, that has been a reliable signal that the cycle low had passed.

Another interesting aspect is cycle duration, indicated by the intervals shown in the last column of the table. Most of the cycles (five out of eight) have occurred over 10 to 15-year intervals. The two four-year intervals around World War II are anomalies.

The 24-year interval between the last verifiable cycle is truly exceptional (from the cycle low in 1974 to the cycle high in 1998). As you can see, no other intervals in the past century have been nearly as long. This can perhaps be explained by the activist monetary policy that started in the 1980s. The Federal Reserve has stepped in quickly with monetary fixes during each period of economic distress.

So where does that leave us? If 2009 was indeed the current cycle’s bottom, that means 11 years will have passed between cycle high and low. That is within the 10 to 15-year range for cycle intervals. But only time will tell if that is long enough to digest the excesses fostered by the abnormally long 24-year interval in which the market was advancing, without a cycle low.